As the winds of war gathered menacingly throughout Europe and across the Pacific, Hitler’s Third Reich extended its odious apparatus to the farthest outpost in the East… Shanghai. The Nazis were everywhere in Old Shanghai – in the clubs, in the streets and on the Bund. They were a monstrous collection of careerists and criminals, perverts and parvenus, fanatics and fakirs, gauleiters and goons. This is their story…

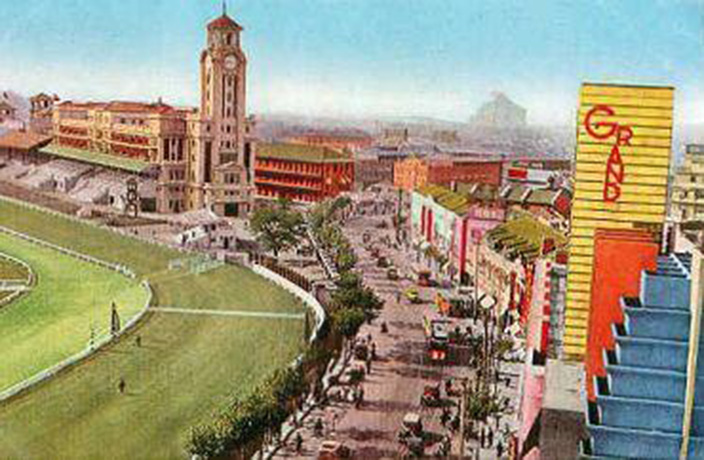

Shanghai, August 1938 – It was the first thing they saw as their boat sailed towards the Bund, and what horror they must have felt upon seeing it. For the first boatload of Jews escaping persecution in Germany, the sight of the Nazi swastika flying proudly on top of the German Consulate in the Glen Line Building at the northernmost end of the Bund must have filled them with panic, fear, loathing and disgust, and no doubt a daunting realization that this so-called ‘safe haven’ of Shanghai – the only place in the world which unconditionally offered them refuge – was perhaps not so safe after all.

But they were safe, much safer than where they had come from, at least. Although the Nazis kept tabs on Shanghai’s Jews (totaling some 25,000, including 20,000 refugees before immigration was halted in August 1941), compiled lists of names, drafted dossiers on key Jewish individuals and assiduously reported all this intelligence back to Berlin, the party proper had no extraterritorial power in Shanghai’s Concessions, which were governed by the French and the internationally administered Shanghai Municipal Council.

“It was something like ‘live and let live’ among the different communities,” states Dr. Astrid Freyeisen, author of Shanghai and the Policy of the Third Reich. “Before the war started, Shanghai’s expatriates were mixing a lot on an everyday basis. The Germans may have had this strange, crazy ideology that other foreigners didn’t agree with, but that was it.”

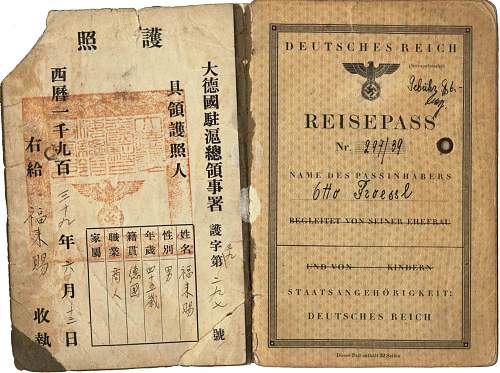

While those “strange, crazy” Germans may have been able to mingle freely with Shanghai’s other foreigners, the Nazi Party dominated their life here. Shanghai’s German population numbered 2,400 in the 1930s, of which 300 were party members – a high percentage compared with the Fatherland.

Although ordinary Shanghai Germans operated outside the Nazi Party, none of them were spared its reach after Hitler assumed absolute power in Germany in 1933.

“Rumors spread throughout the Jewish Shanghai community in 1942 that Josef Meisinger was plotting a mass extermination”

“In the early days, most of the Nazis were small potatoes in the German companies here, not the big laoban, says Freyeisen. “After 1933, there was a big switch, and everybody followed suit. The German Consulate in Shanghai became very pro-Nazi very quickly.”

It was good for business to join the party, and no German businessman got ahead without being a devoutly loyal party member. Membership meant entry to an elite social and business set that non-party members were precluded from.

Nazis paraded in public adorned in full regalia (uniforms, flags, banners, ensigns) and were cheered on enthusiastically by inflamed German crowds. Local party leaders organized receptions to mark Hitler’s birthday (“Alles Gute zum Geburtstag, Mein Führer”) and other Nazi milestones.

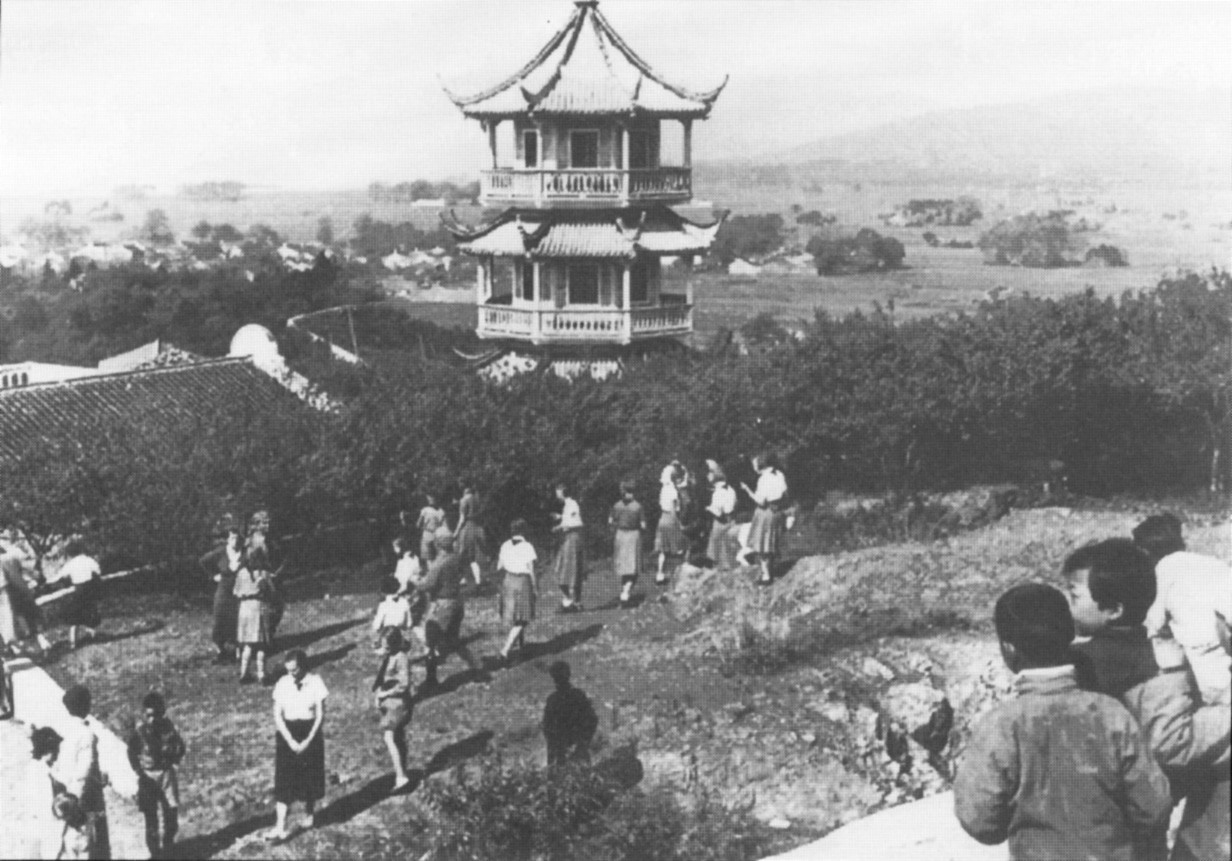

After the war in Europe broke out, local Nazi leaders issued orders that all Germans withdraw from “enemy” clubs and expel “enemies” from their own clubs. There were local chapters of the SS, the SA, the Gestapo and the Hitler Youth. Young German girls were taught the three mainstays of German womanhood, “Kinder, Küche, Kirche” (Children, Kitchen, Church), while boys as young as 10 were groomed for a lifetime of service to the Reich.

There was not a facet of German life in Old Shanghai which the Nazis did not control or seek to control through the slavish obedience of its members or a hideous contrivance of fear, threat and vindictiveness directed against non-members.

“They put a lot of physiological pressure on other Germans,” says Freyeisen. “They issued leaflets to Germans saying ‘Don’t buy in Jewish shops’ and things like that. Of course, everyone was scared.”

They had good reason to be. The Nazi Party in Shanghai was populated with some of the most notorious individuals in the East: Sociopaths with a blind loyalty to Hitler and National Socialism, and a callous lack of empathy for their victims.

There was Dr. Robert Neumann, a pathologist who, before coming to Shanghai, performed human experiments on live subjects in the death camps of Auschwitz and Buchenwald. In Shanghai, he gave speeches to Chinese students, trying to instill his racist ideology among them.

There was the German Colonel of Police, Josef Meisinger, whose sole aim was to crush other Nazis whose loyalty to the Führer he considered to be “lukewarm.” And enemies of Shanghai’s Gestapo Chief, Gerhard Kahner, would end up either fleeing the city or, worse, vanishing under mysterious circumstances.

But as monstrous as they were, these party members were, in reality, profoundly second-rate, essentially B-list Nazis who couldn’t make the grade back in Germany. “After 1941, they wouldn’t send any first-class Nazis to Shanghai because they needed them all in Europe,” states Frank Hollmann, a German journalist based in Shanghai, who helped Freyeisen research her book.

In 1937, the city of Shanghai was occupied by the Japanese and, by 1942, following pressure from its wartime ally Germany, the Japanese instructed all Jews from Germany and German-occupied lands (or “stateless refugees,” as the Japanese euphemistically described them) to move into the Hongkou ghetto. Although the ghetto came under Japanese not Nazi rule, Shanghai’s Jews were fearful of the party’s influence over the Japanese.

“Regarding the Jewish Question, the Führer is determined to clear the table,” Joseph Goebbels infamously declared.

Rumors spread throughout Shanghai’s Jewish community in the summer of 1942 that Meisinger was plotting a mass extermination. Freyeisen and other historians have never discovered any evidence of such a plan, although she concedes it is “absolutely possible” that Meisinger devised one.

“This man was so cruel, hated Jews so much, was such a racist,” says Freyeisen. “He was also crazy enough to think that he would be able to convince the Japanese of such a plan. But the Japanese didn’t care for his opinions at all.”

Neither did the SS high command. When Meisinger cabled Berlin to say he had found a Buddhist monk in Shanghai who could help the Germans conquer Tibet in order to keep the British out, he was demoted in rank.

“He was told, I think even from Heydrich himself [Reinhard Heydrich, Himmler’s deputy in the SS], not to cable such bullshit,” says Freyeisen frankly. “But it just shows how crazy this guy was.”

“Hitler may have been dead for three months but his devotees in the remote Nazi outpost of Shanghai were still slavishly loyal to their beloved Führer”

As for the ‘final solution’ for Shanghai’s Jews, Freyeisen says it is based on one main source – a Japanese Consulate official, Shibata, who claims to have prevented the plan.

“But there’s no written evidence, nothing that backs his story,” says Freyeisen. “In fact, I have come across some files in the US National Archives which says Shibata only invented the story to get some money off the Jews who he claimed he had rescued. Nobody really knows.”

Nevertheless, the Nazis kept a close eye on what the Jews did and dispatched countless reports back to Berlin.

“You find a lot of that,” says Freyeisen. “For example, [words like] ‘The Jews are coming in increasing number, they take up this and that position.’ But there was never any action taken. It was just checking what they were doing. And there were lists of names, which is always a worrying sign.”

After the German surrender in May 1945, the Red Cross in Shanghai released its own list – those of surviving Jews in Europe. Family members rushed to see which of their relatives survived the Holocaust. Few had. Soon after, news of what had happened in Europe reached Shanghai, but the flame of the Third Reich still took a while longer to be extinguished.

In fact, as late as August 1945, the German Residents’ Association in Shanghai held elections which fielded both Nazi and anti-Nazi candidates. The poll produced a solid victory for the Nazi Party, which won all but one of the seats on the association’s board of directors.

Hitler may have been dead for three months, his corpse unceremoniously burned beyond recognition after he took his own life in his Berlin bunker, but his devotees in the remote Nazi outpost of Shanghai were still slavishly loyal to their beloved Führer.

Former Shanghai Hitler Youth Werner Noll remembers the last days of the Nazis in Shanghai.

“In August, there was still a loyalty celebration – Traufeier – in the auditorium of the Kaiser Wilhelm Schule,” he told That’s. “Someone from the German Consulate General spoke. The SA stood on the long side at one end with the Hitler Youth Flag and we Hitler Youth stood on the other side with an SA Flag. Before the first row of seats sat a string quartet that played Hitler’s favorite march, the Badenweiler Marsch. It was somehow festive and spooky at the same time.”

In truth, it was the final dying embers of what was meant to be a 1,000-year Reich.

0 User Comments