Many present-day Beijing residents can only imagine what the capital looked like 34 years ago. A time before high-speed railway stations and trendy Sanlitun coffee shops – back when 798 Dashanzi Art District produced steel rather than artwork.

Scottish photographer Bruce Connolly has been fortunate enough to witness changes in the capital for more than three decades.

Connolly first arrived in Beijing by train in 1987 at a time when China’s Reform and Opening-up was still in its infancy. And with his camera always by his side, he’s built up a comprehensive collection of photos.

Although at first he never imagined settling down in the Middle Kingdom, Connolly spent time working in Guangdong before moving permanently to Beijing.

READ MORE: Meet the Photographer Behind ‘Snapshots from a China Gone Past’

That’s sat down with him to talk about changes he’s witnessed in the capital since he first arrived 34 years ago.

Before coming to Beijing, you had some vague preconceptions about China. Did you ever imagine you would stay here so long?

No, at that time it was financially very difficult for me as a school teacher to settle down in China. Airfare was expensive, and I was lucky to come here in 1987 by train.

Having traveled through the former Soviet Union and Mongolia, I was expecting China to be strict, austere and formal. In fact, it was incredibly friendly. The very first words which were said to me at the border crossing were “Welcome to China!” as the border guard shook my hand. The same thing happened at Beijing Railway Station.

Beijing Railway Station concourse, 1987

I’d walk outside the Friendship Hotel (in Zhongguancun, Haidian district) and see guys riding bicycle carts loaded with melons. If you look at the photos, you’d see a different city. Young people today look at the photos and say things like, “I grew up there!”

Haidian street scene nearby the Friendship hotel, 1987

When you returned to Beijing in 1994, you stayed in the Overseas Chinese Hotel in a hutong area of Beixinqiao, Dongcheng district. What was it about the hutong which fascinated you?

It was a completely different life from other parts of Beijing. People there lived a hutong life. I had to study it because, at that time, there was very little information in English.

In the hutong, you lived the life of the people which was very different from others in modern parts of Beijing even at that time.

And you can still find that hutong life in parts of Beijing today.

Hutong in Beixinqiao, 1999

However, I also realized back in 1994 that the hutong were not popular among ordinary Chinese people. They were seen as old. I would bring tour groups from Scotland, and they all wanted to see the hutong areas.

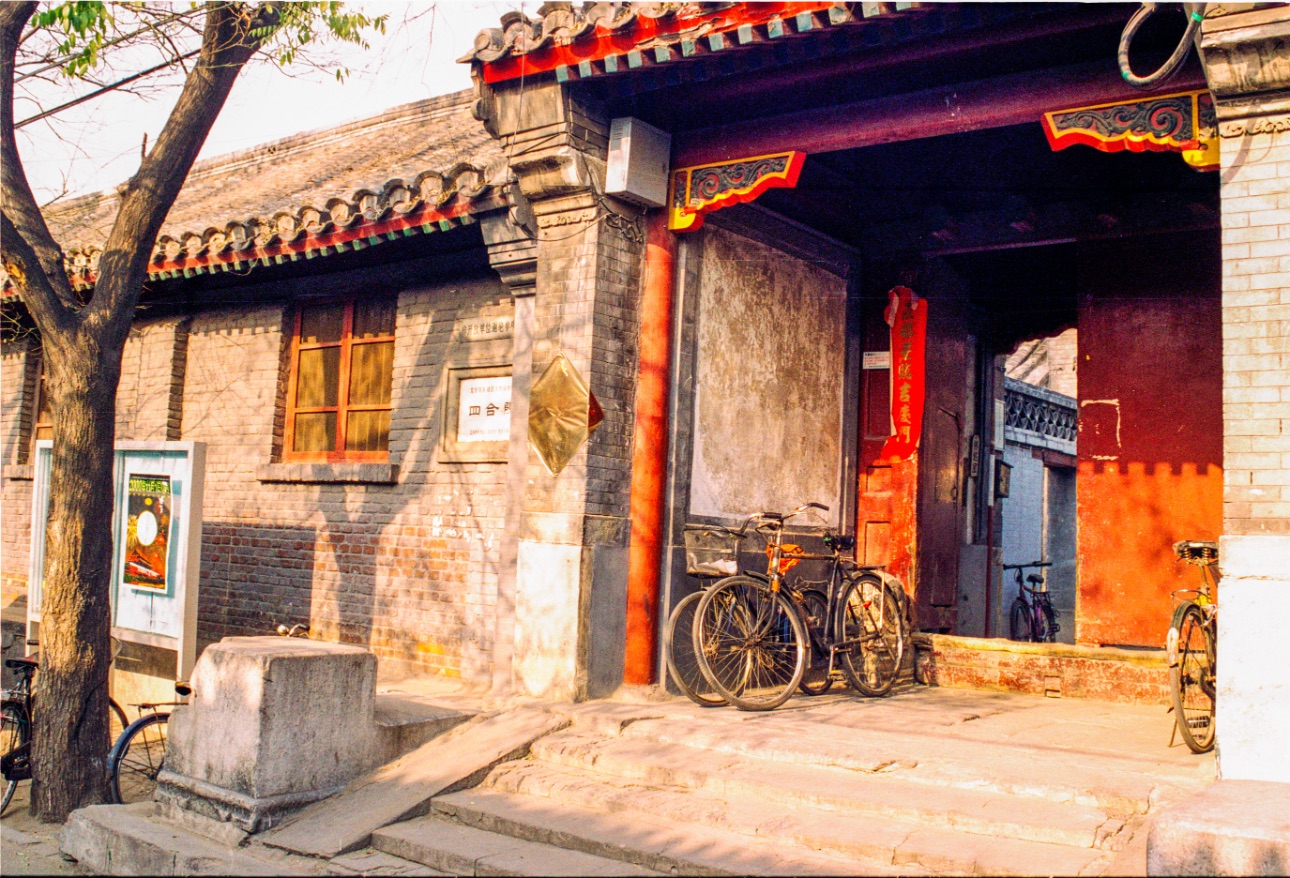

Entrance to courtyard at Qiangulouyuan Hutong, 2000

But my Chinese colleague at the time didn’t want to go simply because they were old. For many Chinese people, they were seen as out of date.

Nowadays there are some hutong such as Nanluoguxiang which have become gentrified. Is there a danger that might happen to other places?

There was a danger. But I don’t think that’s the case now. Many have now realized the value of the hutong. In 2000, I lived in a siheyuan (a Beijing-style courtyard). It was a five minute-walk from Nanluoguxiang, a traditional north-south hutong alley. There was one small backpacker bar called the Pass-By Bar, the kind of place you might find in Yangshuo or Dali.

Pass-by Bar courtyard, Nanluoguxiang

You could find lots of local people, local markets, etc. It was wonderful! After 2008, Nanluoguxiang became a tourist hotspot where people from all over China coming to Beijing wanted to visit. It was jammed with people, so I stopped going. I used to go there for solitude. I would sit in the bar, read and mind my own business.

A busy street scene in Nanluoguxiang, 2015

In the new CBD area, are there any buildings you recognize from today which were still there during your early days in Beijing?

The original China World One is still there. Coming towards Guomao, the first building you came to was part of the original China World development.

Beijing CBD, 2010

On Guanghua Lu, there are houses for the factory workers which are still there. Just to the south of the China World Three building, you can still find some of the old worker’s homes. However, the factories have all gone.

I remember around 2003, we started hearing reports about the city building a CBD. You looked at it, and it was old rundown areas. A lot of it was quite dilapidated. In fact, at Hujialou, just north of the CCTV Tower, you can find the houses of the factory workers which date back to 1950. On one side of the road is highend real estate. And on the other are these houses.

Old apartment buildings in contrast with CCTV Headquarters and China Zun (under construction), 2017

798 Art District (Dashanzi) used to consist of military factory buildings. Meanwhile, Shougang used to comprise steel factories and now includes venues for the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics along with a cultural area. Tell us about the changes you’ve seen in these places.

The factories in Dashanzi, like many of the state-owned factories, were not competitive on the world scene.

Dashanzi 798 coal yard and gantry, 2016

The big debate was that if the area was pulled down, it could be used as real estate property. But many wanted to keep it as they saw it as part of the heritage of Beijing. It initially became an artists’ community before it was more gentrified.

Shougang was on a much bigger scale. The first time I saw the area was in 1995. I took Line 1 out to Pingguoyuan. I saw a lot of smoke and realized it was the steelworks! They weren’t in the guidebooks. But I later learned it was one of the biggest industrial plants in northern China.

Shougang Park no.3 blast furnace, 2021

In the early 2000s, I was taking photographs from the CCTV Tower. There was one photograph, looking towards the western hills, where you could see all this smoke and steam. And then, if you expand the photo, you can see the cooling towers and chimneys of the steelworks.

Again, there was this debate about whether to use it as real estate development or keep it as part of the city’s heritage.

I’ve been twice to Shougang, recently. It’s great for me as a photographer that they’ve kept it.

Dining beside the lake at Shougang park, 2020

Let’s talk about photography and how that’s changed during the time you’ve been in China. What was it like photographing when you first arrived in China? How does modern photography allow you to better tell stories about Beijing today?

When I first came here, I was using a 35-millimeter Canon camera. When you took your photos, you had to economize.

To capture certain images, such as the inside of a train, was quite difficult.

However, with modern photography, everything is much easier. I go into hutong alleys in the dark, and I can just set the camera for low-light filming for a night scene. Hold the camera still and it will take five or six shots. So, you find that you’re able to take shots of poorly-lit hutong, with good lighting in the photographs.

Xilou Hutong near Yonghegong, 1996

A digital camera has opened up a whole new game for me.

This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

[All images via Bruce Connolly]

0 User Comments