When I began writing this article, my plan was to open with a reference to a survivor of sexual misconduct in China. Initially that meant focusing on any number of university cases, from the overdue retribution for the tragedy of Gao Yan’s suicide at Peking University in 1998, to the successful student petition at Guangzhou’s Sun Yat-sen University to dismiss Professor Zhang Peng for sexual assault on July 10.

By late July, instances of victims speaking out against their attackers moved from beyond academia and into the workplace, changing the focus to NGO founder Lei Chang, prominent journalist Zhang Wen and an executive at Mobike. I realized it’s a losing game to try and hinge this story on the most recently accused, whoever he may be, because its significance goes beyond the poor behavior of any one individual.

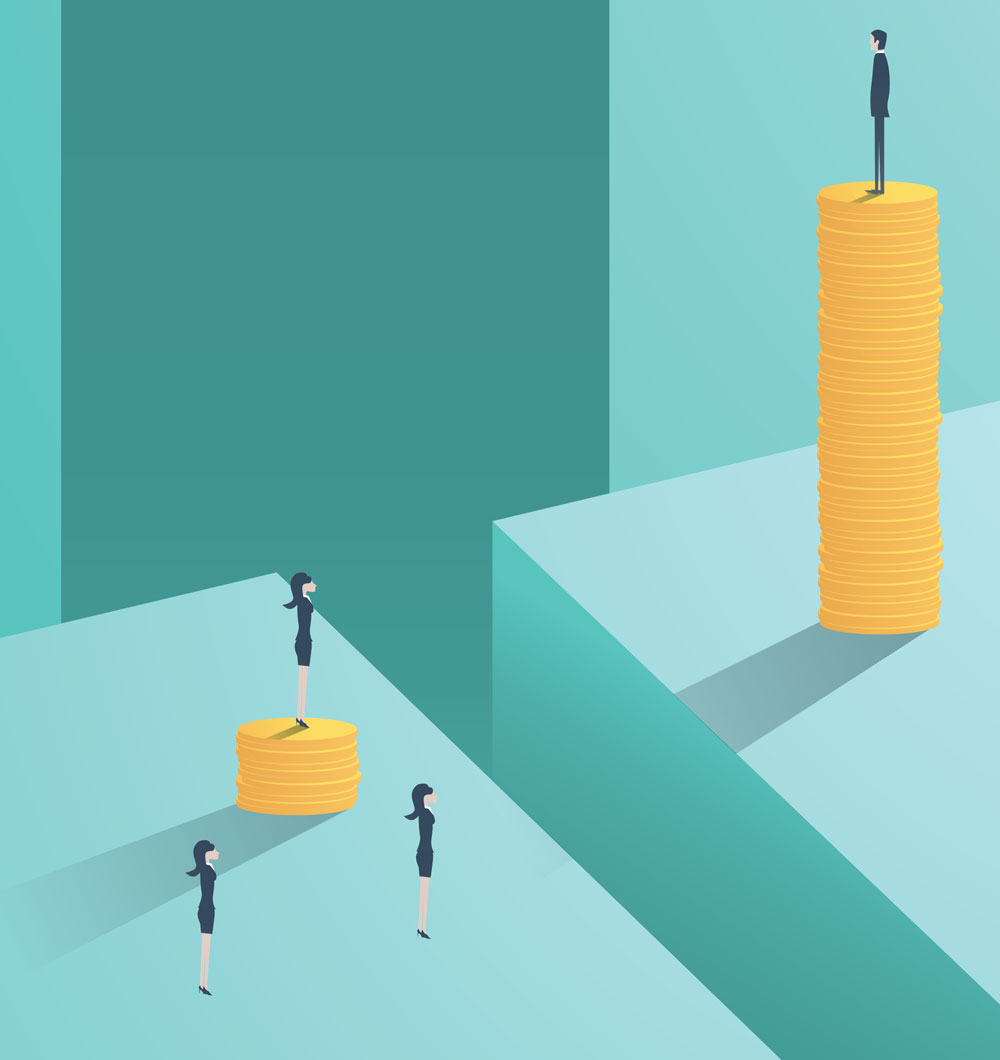

As women continue posting testimonials that gain brief traction on WeChat, Weibo and even occasionally in mainstream Chinese media, two things remain constant: the entrenched gender inequality, power dynamics and lack of education about consent that lead to sexual harassment and assault, and the women and men campaigning to advance gender parity in China so that everyone can move through the world without fear of sexual violence.

First of Many

It’s difficult to pinpoint when China’s version of #metoo officially began, especially because advocates against anti-gender-based violence in China long precede the hashtag, but New Year’s Day 2018 brought a clear milestone. Luo Xixi, a former PhD student at Beihang University in Beijing, published a Weibo testimonial accusing her former advisor, Professor Chen Xiaowu, of sexual assault, becoming the first woman to publicly accuse an individual by name using a Chinese translation of the hashtag, #woyeshi (#我也是). Chen was fired 11 days later.

“I think it was one of the last straws for a lot of people,” says Song Xiaoyu, a volunteer for several women’s organizations and self-proclaimed feminist, of Luo’s testimonial. “What she did was truly brave and inspirational, and a really pivotal point for the movement in China. But you also have to acknowledge all the efforts and follow-up campaigns from others. If not for them, she would have created a first wave, but there wouldn’t have been any of the follow-up waves.”

READ MORE: #MeToo Gains Steam in China After Beijing Professor Fired for Sexual Misconduct

In November 2017, Sophia Huang Xueqin, an independent journalist and women’s right advocate, conducted a nationwide online survey of over 400 women in media about their experiences with harassment and assault. The results were shocking: 84 percent of the respondents said they’d been harassed or assaulted in some form, with 20 percent reporting that it had happened five times or more.

“You can see how common it is. So many of us have the same experience but seldom speak out, never mind filing an official complaint,” says Huang. “We journalists are supposed to be more sensitive, more resourceful, have more of a voice, but when sexual harassment happens, we also keep silent. I came to realize sexual harassment is about power, inequality and gender discrimination, no matter who you are and where you work.”

The testimonials of late July and early August 2018 do indicate that a culture of harassment exists in many industries and sectors. Experts have been surprised and impressed by the number of brave women coming forward.

“Several Chinese women told me that they thought students have more liberty to speak out compared to people who are in the workforce and may be scared of losing their jobs,” says Joanna Chiu, a journalist and co-founder of women writers’ and artists’ collective Nüvoices. “It was such a pressure cooker of frustration and anger that it seems like when some people started talking about cases outside universities, more people were galvanized to speak out, too.”

READ MORE: Joanna Chiu on Empowering Women Writers and the NüVoices Launch

First coined by Tarana Burke in 2006 before it eventually became the de facto term used by survivors speaking out with their stories, #metoo originated in the US but it coincided with a gradual uptick in awareness throughout China about the need to address gender-based discrimination and violence. Journalist and leading expert on women’s rights in China, Leta Hong-Fincher, explores these issues in detail in her new book, Betraying Big Brother, which was released this September.

Hong-Fincher asserts that China’s version of #metoo is a homegrown phenomenon. “The only thing that is borrowed from outside of China is the actual hashtag,” she adds. “Over the years, many different factors have led to a much broader awareness among young women, urban educated women in particular, about sexism and misogyny in Chinese society. And they identify it as an injustice.”

In fact, Chiu points out that “it’s been a trend in China for victims to turn to social media when institutions fail them for years,” referencing a 2016 case in Beijing that she wrote about for Foreign Policy in which a sexual assault survivor posted the CCTV footage of the attack online, which then went viral.

For Huang, these cases and the general lack of faith in institutions (of the respondents to her survey, 55 percent dealt with the assault by just “keeping silent and staying away”), further highlight the need for legislative support.

One major piece of recent legislation in China that has had a positive effect on this issue is the Anti-Domestic Violence Law, which went into effect in March 2016.

“[It] was a huge legal milestone,” says Hong-Fincher. “But in spite of its legal importance, the Anti-Domestic Violence Law hasn’t been enforced properly.”

READ MORE: Will China's Anti-Domestic Violence Law Evoke Change?

The law makes it easier for victims of domestic violence to seek legal recourse and specifically to file restraining orders, but in addition to being enforced only sporadically, it contains several blind spots. It provides no protection for same-sex couples, and though its parameters cover several types of intimidation and abuse, it does not explicitly mention sexual assault or harassment.

The term ‘sexual harassment’ is noted briefly in several Chinese laws, including the Law on the Protection of the Rights and Interests of Women and the Special Rules on the Labour Protection of Female Employees, according to the South China Morning Post, but no law actually defines what constitutes sexual harassment. An entity that isn’t legally defined is much harder to fight.

The Way Forward

Finding long-term solutions to combat sexual harassment and gender-based violence is something that advocates across the country have been doing for years.

In addition to her work with women’s organizations, Song Xiaoyu volunteers her time to conduct sex education workshops for high schoolers, focusing on safe sex and an understanding of consent. She aims to end to the culture of taboo and shame around sex, which is an underlying cause of sexual violence.

“I find it really liberating in a sense, because I never had that,” she says of the discussions between students in her classes. “For me, sex education in school was this: the biology teacher walks into the classroom, puts in a set of DVDs, blushes, and then just says ‘go watch this,’ and walks out. Respect of human bodies is a fundamental part of sex ed. It’s not just about the clinical parts. It’s also teaching you how to love and respect others.”

For adults in the workplace, the focus is on workshops and training to increase awareness of consent and the behaviors that lead to a culture of harassment. Lilian Shen has founded several organizations in Shanghai dedicated to this topic, including Women Up, which holds workshops and panels dedicated to anti-gender-based violence, as well as Queer Talks. She also notes an uptick in feminist training courses available for hire by companies, included one she attended run by Shanghai-based company Xi Tao.

Together with the NüVoices team of board members, Chiu is aiming to provide support on several fronts through NüVoices, including a crowdsourced Google doc circulating global resources for sexual assault survivors. In August, NüVoices released their updated code of conduct and anti-harassment policy, laying out in unequivocal parameters which behaviors the organization will not tolerate.

"Our society hasn’t changed a lot, but the young generation definitely has, especially young girls with higher education. They don’t want to endure the gender inequality of our society"

— Lü Pin, founder of Feminist Voices

Chiu also recently collaborated with the World Association of Newspapers and News Publishers (WAN-IFRA) for a webinar publicizing their new handbook on sexual harassment guidelines. Though it’s specific to newsrooms, the guidelines could apply to any company.

“I’d highly recommend that all companies and organizations think about what they want to have in a code of conduct and then make sure that all participants and partners read and agree to the code,” she says, as companies can step in to create a safe atmosphere until legal protection catches up.

At the same time that these calculated efforts to promote change are cropping up around China, positive depictions of feminist ideas are appearing in a more gradual but also more pervasive form: in pop culture and advertising. A recent example is the immense popularity of Wang Ju, a contestant on game show Produce 101 who is outspoken and proudly defies China’s beauty ideal of thin, demure women, leading writer Wang Qianning from Sixth Tone to deem her “a new brand of female role model.”

This is happening alongside high-profile ad campaigns that specifically target urban educated women with messages of gender equality and empowerment, like a 2016 viral ad by beauty brand SK-II that aimed to humanize China’s stigmatized ‘leftover women.’

SK-II's viral 'Leftover Women' ad from 2016. Outside of China? Watch on Youtube here.

Though arguments against this diluted corporate feminism can be valid, Hong-Fincher sees their existence as positive overall for China specifically.

She notes: “Regardless of whether you think it’s good or bad for corporations to be using the idea of feminism to sell products, I think the growing number of advertisements that use women’s empowerment as a central theme indicates the enormous popularity of equal rights for women among the population at large.”

Changing Attitudes

“The thing about feminism,” says Song, who passionately identifies with the label, “is that it teaches us to critically think about a lot of things, not just about women. It’s not just, ‘women want all the rights.’ Or, ‘women are man-haters.’ It’s not as narrow-minded as that! If you help women get equal rights, you are helping everyone to get equal rights.”

The conversation surrounding sexual assault has evolved in innumerable ways in recent months, but one of the most notable is that it is gradually bringing awareness to mainstream society.

“I think a lot of these issues used to be seen as things that only feminists talk about, but now it’s something that everyone is talking about, because people are realizing it’s not just something that affects ‘those people,’” Shen says. “It affects everyone.”

Part of the focus of Shen’s work at both Women Up and Queer Talks is aimed at encouraging intersectionality and raising awareness for the fact that an issue can still be meaningful even if it hasn’t yet affected you directly. This inability to see beyond one’s own experience, pervasive in patriarchal cultures around the world, is why survivors who’ve shared their stories in years past were greeted with victim-blaming and slut-shaming rather than empathy.

“There isn’t technically a term for intersectionality in Chinese,” Shen says. “When we had this as a topic for Queer Talks, we translated it as jiaocha xing linian (交叉性理念). The concept of intersectionality isn’t necessarily widespread in China, but the idea that these issues are connected if you go down to the root of the problem – I think people understand that.”

Intersectionality highlights the fact that sexual harassment affects women across the socioeconomic spectrum. A representative report from China Labour Bulletin of female factory workers in Guangzhou found that up to 70 percent had experienced some form of sexual harassment, from dirty jokes to indecent exposure.

Changing entrenched sexist attitudes isn’t easy, even if perceptions may be evolving in subtle ways. Hong-Fincher notes that most of the women who are coming out with testimonials likely don’t identify as feminists, while Song points out that change is centered in first-tier cities; in her hometown, “it’s pretty much stayed the same as it was 20 years ago.” Even so, they are cautiously optimistic.

READ MORE: Leta Hong-Fincher on Women's Rights in China

Lü Pin, founder of a prominent blog called Feminist Voices and a long-term women’s rights advocate, sums it up thusly: “My feeling is that our society hasn’t changed a lot, but the young generation definitely has, especially young girls with higher education. They don’t want to endure the gender inequality of our society.”

Enough Is Enough

Earlier this summer, the Shenzhen police department released a WeChat post announcing a targeted effort to decrease sexual harassment in subways, including upskirting. The post states that police are working to “defend women’s right to wear skirts,” according to a translation by That’s Shenzhen’s Jessica Ho, in a cheeky condemnation of victim-blaming culture.

READ MORE: 29 Busted for Sexual Harassment on Shenzhen Metro

In August, Hangzhou also enacted a precedent-setting series of regulations to protect minors from on-campus sexual harassment. Tackling the culture of silencing victims, it requires all staff to report harassment cases to university authorities within six hours of receiving a complaint and offers resources like legal assistance and mental health care, as reported by SupChina’s Jiayun Feng. These incremental changes serve as tiny sparks of positivity.

“It’s hard for people to speak out about this topic, especially in China, where the power dynamics are so ingrained in people,” Shen says. “But everything you enjoy now, no matter where you are, everything around you, it was fought for by someone. And that has affected a lot of things. Even if it might not be measurable or direct sometimes, the effects are there.”

She mentions the work of Zhang Leilei, a Guangzhou-based feminist who campaigned to put up an anti-sexual harassment ad on public transport in 2017, but her designs were rejected and the initiative squashed.

“Soon after her campaign ‘failed,’ multiple cities had anti-sexual harassment ads,” says Shen. “So it’s definitely affected people.”

READ MORE: Feminists Launch Anti-Harassment Campaign on Beijing Metro

A recent example of this rippling effect appeared in dramatic fashion in early August in Xi’an. WeChat account Henyou Xi’an posted an enormous billboard outside a brand new mall proclaiming in bold text: ‘Say no to sexual harassment.’ The billboard has an unequivocal pro-survivor stance, even satirizing common victim-blaming phrases like, “Good girls don’t constantly change boyfriends.”

It caused an absolute sensation on social media, with passersby stopping to pose and take pictures. The most common stance was to mimic the giant red ‘X’ at the center of the billboard: groups of young men and women stood before the massive ad, holding their arms high and crossing them in front of their faces as if to say, enough is enough.

Graphics by Nadezda Grapes and MJgraphics

1 User Comments