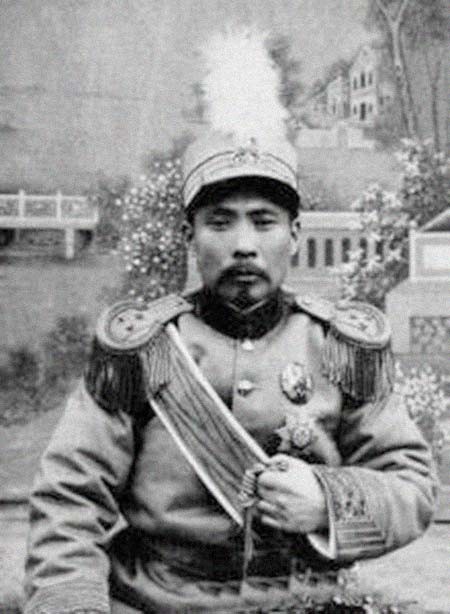

Qi Xieyuan, who was briefly Shanghai’s warlord in 1924, and later a top Chinese military official in the Empire of Japan’s puppet government, finally met his maker on December 18, 1946, executed for treason. This is his story.

In 1907, hoping for acceptance into the prestigious Baoding Military Academy, prospective students lined up in order of height, starting from tallest. Standing dead last and with a lazy eye, the school’s admissions officials scoffed at Qi’s diminutive stature and were about to dismiss him.

Having passed the rigorous imperial exam though as a ‘xiucai,’ Qi would not be overlooked. He confidently called out that while he may not be big, he had the ambition of a swan and could see far into the distance. Impressed with Qi’s bold and direct manner, and perhaps swayed because he was a Tianjiner, as was one of the officials, the Academy decided to give him a chance. Qi’s warlord ascent had begun.

Born in 1885 in Shuntian Prefecture, part of modern-day Tianjin’s Ninghe District, Qi graduated from Baoding in 1909 and continued his military studies in Japan. Upon returning, he joined the Qing Beiyang Army’s 6th Division and quickly rose through the ranks.

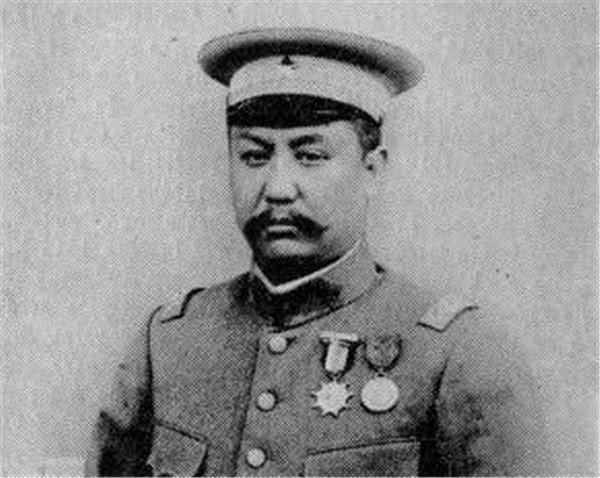

After the fall of the Qing in late 1911 and failed emperorship and death of Yuan Shikai in 1916, Qi became the protégé of Jiangsu province’s military leader Li Chun. Qi was his deputy, as well as the military commander of Jiangning, now a district of Nanjing. Following Li’s 1920 suicide, Qi took control of all of Jiangsu.

Li Chun

Leading up to 1920, China had three main warlord cliques: the Anhui Clique, led by former Prime Minister and one-time Baoding Military Academy instructor Duan Qirui; the Zhili Clique, led first by Hebei province-born former China VP (and brief President) Feng Guozhang and later the ‘Jade Marshall’ and Baoding graduate Wu Peifu; and the Fengtian Clique, led by Liaoning province’s ‘Mukden Tiger’ Zhang Zuolin.

Duan Qirui

Qi, born a stone’s throw from Hebei, was firmly in the Zhili camp. By the time Qi came to power in Jiangsu, Duan Qirui had been defeated by Wu Peifu and company in the 1920 Zhili-Anhui War. Controlling Beiping (today’s Beijing), the Zhili Clique was the main power base in China for the next four years.

READ MORE: The Mysterious Death of Chinese Warlord Wu Peifu

Wu Peifu

Adjacent to Qi’s Jiangsu was China’s economic powerhouse: Shanghai. Historically, the non-foreign concession areas of the city were considered part of Jiangsu. To maintain the peace in Shanghai though, Qi initially accepted the dominion of Anhui Clique-affiliated Zhejiang province warlord Lu Yongxiang.

This fragile peace was challenged in November 1923, when the Wusong-Shanghai Police Commissioner Xu Guoliang, who, while neutral, seemed to lean towards Qi’s Zhili Clique, was assassinated. Lu and associates were heavily involved in the opium trade within the concessions. So was Xu. The military, directed by Lu, protected opium shipments into Shanghai, as did the Chinese River Police, collecting sizable payments in the process.

According to George Sokolsky, a prominent Shanghai-based American journalist at the time, a disagreement in opium profit sharing may have led to Xu’s demise. Open conflict between Qi and Lu was narrowly averted this time, but the inevitable clash would soon come.

READ MORE: This Day in History: Lu Yongxiang – Shanghai's Forgotten Warlord

Lu Yongxiang

In September 1924, Shanghai was the site of a proxy battle between the Zhili and Fengtian cliques, known as the Jiangsu-Zhejiang War. The Zhili Clique, headed by Wu Peifu, backed Qi to overthrow Lu.

There was intense fighting in many areas of western Shanghai, especially the Jiading District towns of Anting, Huangdu and Nanxiang. At least 4,000 were killed, thousands of homes were destroyed, and upwards of 100,000 displaced.

Ultimately, with the help of Zhili stalwart Sun Chuanfang, Qi emerged from 40 days of fighting victorious and briefly became warlord of Shanghai.

A few months later though, in January 1925, Fengtian warlord and Zhili nemesis ‘Dogmeat’ Zhang Zongchang drove Qi out and took control of Shanghai himself.

READ MORE: Coffins, Cigars & Concubines: Dogmeat, China's Basest Warlord

‘Dogmeat’ Zhang Zongchang

Qi fled to safety in the foreign concessions of his native Tianjin. He made a couple of unsuccessful return attempts to warlord prominence, first in 1927 during the Northern Expedition, and then in the 1929-30 Central Plains War under Shanxi province warlord Yan Xishan.

However, he was defeated both times by the ascendant Chiang Kai-shek. Yet another Baoding Military Academy alum, Chiang studied there in 1906, a year before Qi.

Yan Xishan

Yan Xishan

Down but not out, in 1931 Qi sent his son Qi Hongmai to Japan to study military science, foreshadowing the elder Qi’s plans at a comeback. After the 1937 Marco Polo Bridge incident, where Japan commenced a full-on invasion of China from its base in Manchuria, Qi returned to the scene.

READ MORE: This Day in History: The Marco Polo Bridge Incident

He agreed to become one of the Japanese puppet government’s top Chinese military officials, serving as a supervisor of the General Administration of Justice, Commander of the Appeasement Army and member of the North China Political Affairs Committee.

Qi helped clear vast swaths of land near Tianjin to grow crops for Japanese soldiers and was considered ruthless against his Chinese countrymen. His son Hongmai worked with him initially, doing interpretation for the Japanese, but Hongmai got tuberculosis in 1940 and died.

Qi continued to work with the puppet government, which subsequently moved its base to Nanjing, until 1943.

Upon Japan’s surrender, a list of top traitors was published in late 1945 by Chiang’s reinstated KMT government. After starting his warlord career in Nanjing, a city traumatized by Japan’s ruthless invasion, Qi was brought back and sent to Yuhuatai Prison, where he was executed on December 18, 1946.

Before being taken away, Qi was under house arrest at his villa in Tianjin. Knowing what likely fate awaited, he told his youngest daughter Qi Zhizhong that if he wasn’t around in the future, and the KMT continued to be in power, she should reach out to famed Chinese diplomat Wellington Koo.

Wellington Koo

Koo did check on Zhizhong several times, including asking his own daughter to write a letter to Zhizhong in the 1980s. Ultimately though, the KMT didn’t stay in power. Zhizhong left Tianjin for good and began anew in Harbin. Living until the late 1990s, she became a doctor and started her own family, trying to leave the past behind.

READ MORE: This Day in History: Wellington Koo, the Dapper Diplomat

For more This Day in History stories, click here.

[All images courtesy of Wiki]

0 User Comments