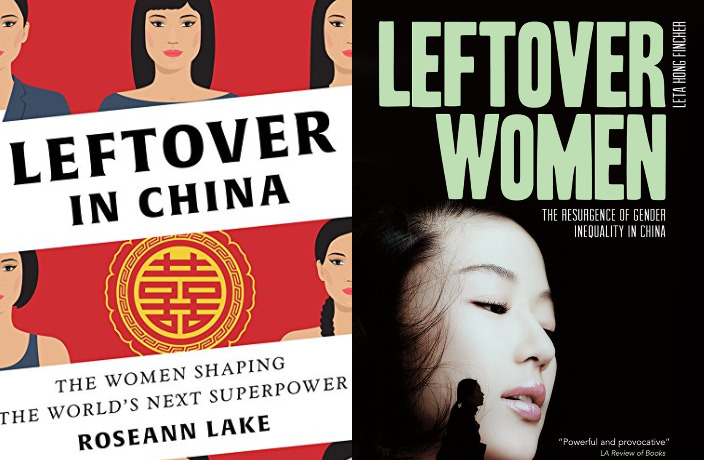

In early February, I interviewed journalist Roseann Lake about her new book, Leftover in China. Less than three weeks later, Lake was accused of journalistic misconduct, making headlines and raising eyebrows among academics, correspondents and China watchers.

Leftover in China explores through interviews and research the concept of shengnv, or leftover women, a propaganda term coined by the Chinese government in 2007 to shame professional, educated women in their late 20s and early 30s who are not married. Lake, a journalist who lived in Beijing for five years and worked as a television reporter, became interested in the topic after speaking about it with her colleagues – independent, highly successful women who nonetheless fell into this category.

“I decided to write this book because these women really impressed me,” Lake told me. “The fact that they exist is a very good thing.”

On February 19, Leta Hong-Fincher, a respected scholar and author of 2014’s groundbreaking book Leftover Women, published a 21-tweet thread on Twitter accusing Lake and her new book of “erasure.”

Despite having corresponded with Lake in the past and being generally considered the English-language expert on shengnv, Hong-Fincher is not mentioned or even cited in the bibliography of Leftover in China.

“This is not fun for me,” Hong-Fincher tweeted. “I can’t sleep. I am in agony. Someone else is profiting from the groundwork I laid and doesn’t even bother to put me in an obscure footnote.”

Shortly afterwards, Lake released a response via her publisher. She lists her own credentials for being well-versed in the topic of leftover women, including a play she produced called The Leftover Monologues in the vein of The Vagina Monologues. The meat of the statement, however, is Lake’s assertion that she chose not to read Hong-Fincher’s book when it came out in 2014, because she was already working on her own manuscript and “chose to stay focused on the stories of the women whose lives [she] features in it.”

“I am not saying that Lake’s overall argument is the same as mine at all, but she drew extensively on my groundbreaking research.”

- Leta Hong-Fincher

In response, many ‘China experts’ and academics expressed support for Hong-Fincher and accused Lake of shoddy journalistic standards. ChinaFile tweeted that they took down an interview with Lake because they weren’t confident that her book “respects basic scholarly and journalistic principles” (though they later decided it did, and re-published it).

“I am not saying that Lake’s overall argument is the same as mine at all,” Hong-Fincher tells me. “But she drew extensively on my groundbreaking research without acknowledging me anywhere, even though she was the one who reached out to me in 2011 and wanted to exchange thoughts.”

Hong-Fincher has not accused Lake of plagiarism per se, but she is encouraging a line-by-line reading of both books by all reviewers of Leftover in China.

“It takes a huge amount of work to compile a comparison chart of similar sentences from both books and I have not yet begun to do so systematically,” Hong-Fincher said on Twitter in February. “But reviewers of the book MUST.” (Full disclosure: I read both books at the same time, annotating them as I went, but I have not done a sentence by sentence comparison.)

In Leftover in China, Lake does not plagiarize from Hong-Fincher, and their key points are different enough that she could have theoretically written it without drawing upon Hong-Fincher’s work.

Lake’s book, which chronicles in pert and effervescent prose the tribulations of four unmarried women in Beijing, is aimed at Western readers who may know little about China but are interested in learning more about global feminism. At one point, she translates meishi (没事) as “Hakuna Makata,” and she occasionally plays up her role as a “confused foreigner” stand-in for the reader; the book opens with Lake returning to work after Spring Festival wondering why the women in her office are out of sorts, before finding out that they’ve been chided by their families for still being unmarried.

Lake compares China’s current attitudes toward leftover women with American sex and dating in the 50s and 60s, theorizing that tradition will eventually modernize the way it did in the US, as men become more comfortable with the idea of a dual-earning household.

“There’s a quote in the book that I think really summarizes a lot of what’s going on with these growing pains,” Lake told me. “It’s from a demographer who specializes in studying female education rates and marriage trends around the world. He said: ‘Men [in China] are looking for women who no longer exist, and women are looking for men who have yet to exist.’ I think that nails it. It will work itself out.”

Hong-Fincher’s book is bleaker, in part because her impressive research reveals how deep-seated these issues lie within China’s tradition and government. Some critics of Lake’s book have claimed that she is more optimistic because she doesn’t have the big picture knowledge that Hong-Fincher’s book provides.

Hong-Fincher is meticulous and academic in her approach, summarizing key points at the end of each chapter and relying heavily on hard data. She provides a sobering, groundbreaking look at gender inequality in China, with a specific focus on how the patriarchy has caused highly-paid, successful women to lose out on China’s real estate market, and another focus on intimate partner violence. These are two topics that Lake barely touches on.

In fact, a major divergence between the two texts is that the bulk of Hong-Fincher’s book zeroes in on how women suffer when they get married solely to avoid becoming leftover women, while Lake’s book is more focused on women who haven’t yet made the leap and are still navigating the dating world.

The books, therefore, are very different – but the claims of “erasure” are still valid. Though Lake could have theoretically written Leftover in China without using Hong-Fincher’s research at all, the question we should ask is: why would she want to?

In a follow-up interview, Lake shed some light on this decision. Essentially, Hong-Fincher was not the first person to coin the phrase “leftover women” in English (though she’s done more original research about the demographic than anyone else), so Lake didn’t need to cite Hong-Fincher just for using the term. Because Lake hadn’t officially interviewed Hong-Fincher and did not quote one of her texts for the book, she did not need to include her in the bibliography.

During a talk at The Bookworm in Beijing on March 24, Lake gave a similar response to a question from journalist Joanna Chiu about the allegations of “erasure” of a woman of color, which Chiu recorded and posted on Twitter:

“I have not used Leta’s research in my book, and therefore she’s not cited. It was certainly not an effort to ‘erase’ her. I don’t believe she has been erased. She has done important work on the topic of leftover women.”

- Roseann Lake (Watch full video here with VPN on.)

Her explanations are valid, strictly speaking, to the way citation works. But even so, I can’t see myself or any other responsible journalist actively choosing to avoid reading such a seminal body of work on the topic I was researching. And as Grace Jackson pointed out in her March review of Leftover in China for the Los Angeles Review of Books, it also taints Lake’s purported commitment to feminism that she wouldn’t go out of her way to reference a woman of color who is the most groundbreaking expert on leftover women.

“Roseann Lake said she never read my book because she wanted to focus on writing on ‘leftover’ women in ‘her own voice,’” Hong-Fincher told me. “You might want to ask her what she was afraid would happen if she read my book while writing hers.”

Lake’s exploration is unique and engaging enough that she could have read Hong-Fincher’s book for reference, cited her where appropriate, and then gone on to follow her own research where it took her without any fear of publishing a book that’s too similar to Leftover Women. But she didn’t.

If there’s anything to be taken out of this, it’s to always cite your sources. But more importantly, uplift other women in your field, above and beyond what might be required by a publisher or by general journalistic or academic standards. If you don’t, you might not be a plagiarizer, but neither are you working to advance gender parity, the cause that’s at the heart of both of these books.

Leftover In China: The Women Shaping the World’s Next Superpower by Roseann Lake and Leftover Women: The Resurgence of Gender Inequality in China by Leta Hong-Fincher are available on amazon.com

2 User Comments