If Shenzhen's Huaqiang North Electronics Market had an official noise, it would be the scream of packing tape coming off the reel.

The tape is wrapped around boxes of electronics before they are shipped across the world. But things have been quieter recently, with the rise of e-commerce and an influx of retail outlets lining a new pedestrian street in the market.

To find the ‘real Huaqiang North’ of local lore, you need to visit the factory-direct kiosks in the massive buildings along the periphery.

Through plastic-flap doorways, cigarette smoke drifts across cramped hallways where tech ranging from SD cards to musical plant vases are sold – in bulk.

Inside one of these buildings, up an escalator narrow enough to rest my hands on both rails without a stretch, I find Wu Huayang sitting in a shop holding a fidget spinner.

A seller balances a fidget spinner on his thumb

A seller balances a fidget spinner on his thumb

It’s a simple toy: a central bearing with weighted metal or plastic that rotates around it. It’s also cheap to manufacture and, when I first visit in early June, wildly popular in Western markets.

Fidget spinners have been a boon for Wu, for Huaqiang North and for the small manufacturers that cashed in on the trend.

After sitting in the shop for about 30 minutes, a man enters, refuses a cigarette and places an order worth RMB50,000 – all within about five minutes.

“He’s selling abroad,” Wu says, naming the best markets for the toy as England and the US, where they are both touted as an ADHD treatment and banned from schools as distractions.

The Huaqiang North Electronics Market sits at the nexus of China’s export supply chain, with a sprawling Foxconn plant about an hour north. Countless factories across the region are served by the Port of Shenzhen, by some measures the third busiest in the world.

From selfie sticks to Apple Watch knockoffs, it's all sold in bulk

From selfie sticks to Apple Watch knockoffs, it's all sold in bulk

If there is a place that can provide a cross-section of China’s manufacturing industry it’s Huaqiang North, and looking at the rows upon rows of rainbow-colored fidget spinners lining the shelves in Wu’s shop, you can see that something is seriously wrong.

How many fidget spinners have been made, bought or sold is unknown, with the numbers hidden in a fractured web of Western sellers and small Chinese factories. One Fox Business article dubbed it a ‘500,000,000 fad,’ predicting overall US sales by yearend.

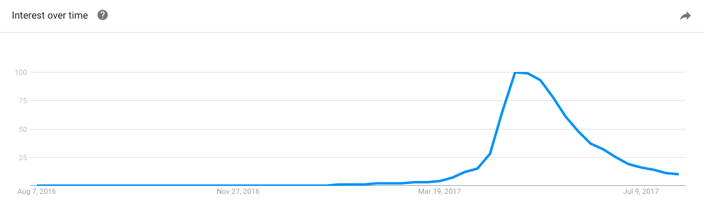

In the search for a more solid number, dozens of other articles turned to Google Trends to gauge the toy’s popularity.

Google Trends rates worldwide interest in a topic based on keyword searches, and on January 15 ‘fidget spinners’ were rated at zero – no interest worldwide.

Only four months later the toys accounted for 20 percent of all sold online and briefly took all 20 slots on Amazon’s top selling toy list, according to Slice Intelligence.

“This craze was one of the fastest growing of all time,” says Marissa DiBartolo, senior editor of trade magazine The Toy Insider.

This Google Trends chart show peak popularity in May

This Google Trends chart show peak popularity in May

Over a few months, they became the topic of countless morning shows, the subject of YouTube videos with millions of views and a sort of ‘school yard currency,’ according to DiBartolo. They were impossible to escape.

But where the real impact of the toy is most obvious – and the most meaningful – is the narrow hallways of the Huaqiang North Electronics Market.

Suffering from double-digit vacancy rates, stores that remain embraced fidget spinners with gusto: an iPhone cable store covered a table with the toy, a store with an English sign reading ‘factory direct phones’ filled one of their shelves. Also stocking them was a micro-SD adapter store, and the neighboring USB drive store. A store specializing in wooden phone cases displayed wooden fidget spinners.

All of these outlets would be happy to take a bulk order for spinners – or introduce you to a friend that could.

“Why am I selling fidget spinners?” says Huang Keqiang, the toys laid over a case of optical switches. “Selling electronics is bad business."

The fidget spinners phenomenon wasn’t unique just because of its speed, but also in how the toy reached Western consumers.

“One of the most interesting things about fidget spinners is that they were not sold at mass retailers,” says DiBartolo. “This was a toy that genuinely became hot through old-school word of mouth and new-school social media madness.”

Popularized through a rocket-fuel mix of Instagram posts and YouTube videos – and originally unavailable on Toys R’ Us shelves - consumers turned to Amazon, highlighting a growing willingness to buy online. Meanwhile, the owners of gas stations and newsstands used Alibaba to order fidget spinners directly from factories.

With no copyright factories were free to produce as many as they wanted, in whatever styles that sold, but instead of a design team crafting new versions, the task was often left to in-house designers. The results range from the brilliant – a fidget spinner that loads with fake bullets like a six-shooter – to the questionable: a spinner containing an electric lighter.

Eight spinners are laid out on a table by Wang Ming, who explains them by ‘generation.’

The first generation is a bulky green plastic thing with a bearing in the center. Later generations are metal, and then colored metal, with the last a cube-shaped spinner.

“You’ve really got to sell all the new ones within a month,” Wang says. “After that, copycat factories mean supply will outstrip demand.”

Baniel Cheung agrees. Cheung is an adjunct assistant professor at the University of Hong Kong and the founder of Integral Consultancy Limited, a group that does market research for companies looking to do business abroad.

“If one (factory) does one product, thousands will do the same product,” he says. “That's a serious problem.”

Rather than describing this as the nature of business, Cheung says it's a systemic problem. A pattern of undercutting prices on similar, unbranded products is a race to the bottom – and he doesn’t see manufacturers breaking out of the pattern anytime soon.

Wang holds up a Bluetooth-speaker spinner. “After one or two months, you won’t be able to sell these.”

Fidget spinners have been a short-term boost, no doubt, but also a sign of trouble.

“Fifteen years ago, when the factories were competitive, they required a bulk order,” says Cheung.

Today, the factories are ready to take orders of a few hundred.

China doesn’t release information on factory closings or relocations, but a June 2016 Wall Street Journal article cites a study showing Hong-Kong-owned factories in the Pearl River Delta plummeted by a third since 2006 to around 32,000 in 2013.

“To be honest,” says Cheung. “In the past five years, I’ve seen many small manufacturers die. Some of them move outside of the country, but those remaining in China can’t rely on low costs, they need to upgrade their technology.”

Cheung believes that undercutting prices on similar quality products isn’t a sustainable model – instead manufacturers should be focusing on establishing brands and creating original products.

“But they simply don’t have tech or branding in their DNA,” Cheung says. “You need money to do it, and even if they have money they don’t know how to.”

Back at Wu’s shop about a month and a half later, things are different.

For one: the shop is gone.

I’m directed nearby, and greet the people I recognize.

They don’t want to talk.

The four men are glowering at their cellphones. To the left and to the right are shelves of phone screen covers wrapped in sterile-looking padding, a contrast with the colored toys that lined the shelves in Wu’s shop weeks before.

“We don’t sell them because we don’t sell them,” a man answers when questioned about fidget spinners.

Business was bad?

Silence and cigarette smoke.

I leave.

Later, an employee at Tian’s International Logistics Supply Chain confirms what Google Trends’ drooping rating already suggests: fewer fidget spinners are being sent abroad. Air shipping to the US by this company dropped from ‘two to three tons’ around April to between 700-800 kilograms in June, we’re told.

“Mass manufacturers are now producing fidget spinners. US consumers are informed consumers and they want to purchase products from companies they trust,” says DiBartolo.

Major retailers, though late to the game, are selling branded fidget spinners, cutting out the small factories vying for business at Huaqiang North that people like Jiang Haoyuan represent.

Jiang says he works in ‘about five’ stores in the area and we chat surrounded by boxes of the toy, which Jiang says are on the way out.

A woman remarks that one box contains spinners that are sold at RMB8 each, but cost RMB12 to make. Jiang doesn’t seem worried. He wants me to look at his phone.

He flips through pictures showing ‘thumb-chucks,’ a ball-and-string toy that whips around your fingers. Then he shows a hand-sized ‘fidget cube’ with buttons and dials, asking what I think.

Finally, he pulls the phone to his chest and motions for me to look from behind his shoulder. It’s a type of phone case I’ve never seen before.

“I’d buy that,” I tell him, and wave a friend over to look. Jiang stops me.

For now, it’s a secret. Jiang wants to be the first on the market – before the copies arrive.

[Images via Sky Gidge, r/t Gizmodo, Alibaba, electro-clinic.fr, dhgate.com]

0 User Comments