In ‘El Piñal: The Lost 16th Century Spanish Outpost in South China,’ our September 2019 cover story, we share the story of El Piñal, a 16th century Spanish settlement, which historians believe to have been located somewhere in the Pearl River Delta.

In 1598, Ming Dynasty authorities allowed a team of Spanish traders from Manila to set up shop in China’s Pearl River Delta. The short-lived trade post of the Spanish Empire is believed to have been located somewhere in the vicinity of Macao, a Portuguese settlement that was buzzing with regional trade activity at the time. While the Spanish newcomers were able to establish themselves in the region for nearly two years, they were eventually driven from their port, named El Piñal, as tensions rose and evolved into bloody conflict between the two European empires in the Far East.

Unraveling the story of Spain’s abandoned outpost in South China is a difficult task and many aspects of El Piñal’s story may never be known for certain, the result of varying historical accounts from the conflicting parties. This fascinating line of historical research is made even more difficult due to the fact that no living person knows with certainty the settlement’s exact location. While there’s no clear consensus among researchers and historians about where the remains – if they still exist – of El Piñal may be located, we came across one hypothesized spot during our research that seems plausible: Qi’ao Island.

Today, Qi’ao Island is connected to the southern metropolis of Zhuhai via a 1,486-meter-long, six-lane bridge. The island presents a convincing case for the modern-day site of El Piñal due to its geographic location between Guangzhou and Macao and its rumored groves of a very particular type of foliage: pine trees (or piñal, in Spanish).

But could a small island off the eastern coast of Zhuhai really have played host to the Chinese mainland’s only outpost of the Spanish Empire? And what led the settlement’s inhabitants to abandon the site less than two years after its establishment? We’ve pored over books and archives, spoken to historians and even visited Qi’ao Island in the hope of shedding light on this captivating chapter of South China’s history.

Calls for Canton

During the 16th century, the Far East was a far different place. The Ming Dynasty ruled over the Middle Kingdom, the Japanese Empire was busy invading the Korean Peninsula and the Spanish were gallivanting through the archipelago we now call the Philippines, colonizing the islands’ inhabitants.

The Portuguese were also in the ‘neighborhood,’ setting up shop in their newly leased settlement in South China – Macao. By the late 1500s, after humble beginnings as a small trade post, the town was transforming into a regional trade and commerce hub. This, coupled with the city’s strategically significant location, gave the Portuguese a monopoly over trade in China in the 16th century.

And so, right before the turn of the century, when the Spanish decided to voyage across the South China Sea from Manila to Canton, their Iberian counterparts were gravely concerned.

In 1598, the governor of the Philippines sent a ship captained by D. Juan Zamudio to China’s southern coast, with the likely intention of establishing a direct channel between Spain’s Southeast Asian colony and Canton. In his paper ‘Enemies at the Gate: Macao, Manila and the “Pinhal Episode,”’ Paulo Jorge de Sousa Pinto refers to the purpose of the trip – as well as the effect of the events that followed it – as “somewhat shadowy” given the contradictory accounts.

“The Portuguese didn’t learn of Spain’s new outpost in Guangdong until April of the following year”

There’s one thing we know for certain, though: Zamudio managed to convince officials in Canton to allow him and his convoy to settle along the coast of Guangdong province and establish a Spanish trading post in China. However, the exact location of the settlement is a matter of scholarly debate and there are multiple theories as to where the Spanish lived out their short tenure in the Pearl River Delta.

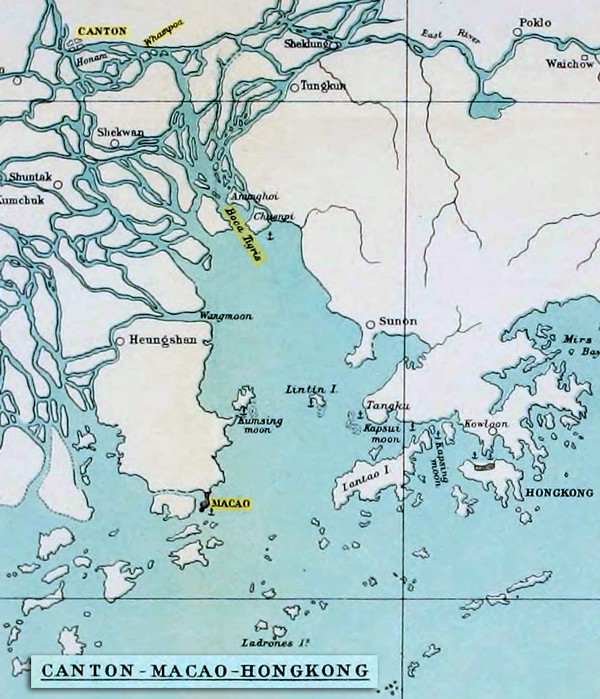

Map of the Pearl River Delta. Image via Wikimedia

The events that transpired over the next two years, referred to as the ‘Pinhal episode,’ [pinhal is the Portuguese equivalent of piñal] would ultimately shape geopolitics and trade in the region for years to come.

Prior to the Pinhal episode, Spain and Portugal had signed the Treaty of Zaragoza in 1529, which divided newly discovered lands between the two empires along an artificial line drawn through the Moluccan Islands. Everything west of the line was fair game for Portugal, while the land and seas to the east were open to Imperial Spain.

Although the Philippines lay west of this decided line, the Spanish decided to colonize the archipelago anyways, in the expectation that Portugal would not protest due to the islands’ lack of spices. By the time Manila came into its own, a royal prohibition on commerce between Macao and Manila was in place.

“There was a royal prohibition (repeated throughout the years), but there was also a long distance between Madrid and China. Practical issues sometimes overlapped official orders because it took a long time for the news to reach Europe and return, meanwhile it could be possible to attempt a local success that could reverse the orders,” Dr. Pinto tells us via email. He goes on to note that the Portuguese operating in Macao had a tendency to obey royal orders, while the Spanish in Manila were more likely to disregard them.

Although it’s not clear the exact date in 1598 that Zamudio and his men arrived in El Piñal, the Portuguese didn’t learn of Spain’s new outpost in Guangdong until April of the following year.

According to an article by John Villier, titled ‘Silk and Silver: Macau, Manila and Trade in the China Seas During the Sixteenth Century,’ upon hearing the news, Macao told Chinese officials that the Spanish were “robbers and insurrectionaries who raise revolts in the kingdoms they enter.” However, China may very well have ignored the claims, as they did not take action to remove the Spanish from the settlement.

At the time, Macao was a Portuguese ‘informal settlement’ that was considered “the exclusive gateway for the Europeans to access China,” Dr. Pinto explains in his paper ‘Manila Macao and Chinese networks in South China Sea: adaptive strategies of cooperation and survival (sixteenth-to-seventeenth centuries).’ Having first settled in Macao in 1513, the Portuguese were granted permission to anchor ships and build warehouses there in 1535, and eventually obtained a coveted lease from Beijing in 1557.

While Macao was experiencing the thrills of success, El Piñal’s fate was never guaranteed. In retrospect, the settlement has been regarded by some as an experiment that was “destined to fail.” For starters, Portuguese sources note that the Spanish were not authorized to settle along the Chinese coast, nor could they build warehouses or step onto the Chinese mainland – once trading was completed, they were expected to leave with the next monsoon. (Spanish sources contradict this notion, claiming that Chinese authorities allowed them to come and settle, as noted earlier.)

Macao’s uneasiness at the idea of a Spanish colony in their backyard is well-documented. And while D. Paulo de Portugal, the highest-ranking authority in Macao at the time, had prepared military action against Zamudio upon learning of his arrival, he was persuaded by others in the city to hold off out of fears of possible repercussions from the Chinese side. But what happened next would ultimately lead to bloodshed.

The Seas’ Misdirection

As Zamudio’s trade post experiment was underway in Guangdong, a man named D. Luis Perez Dasmarinas had begun a voyage to Cambodia, with his armada leaving the coast of Manila in summer 1598. The mission was meant to bring reinforcements and missionaries to the region, per the request of the king of Cambodia. However, the oft-turbulent waters of the South China Sea decided on a different fate for Dasmarinas and his 200-man expeditionary force.

After getting caught in a storm, the Spanish fleet was scattered at sea, with Dasmarinas and part of the fleet ending up somewhere off the South China coast in the vicinity of an increasingly hostile Macao. Pinto notes that Canton authorities allowed Dasmarinas and his men to relocate to the port of Piñal and link up with Zamudio. This is the juncture where the Pinhal episode becomes even more muddled and confused.

Still intending to complete his original voyage to Cambodia, Dasmarinas sent a request to Manila asking for more men and ships, although his pleas fell on deaf ears. Meanwhile, if relations between Macao and El Piñal were tense prior to Dasmarinas arrival, you could imagine how much the additional newcomers made Paulo de Portugal’s blood boil.

Paulo de Portugal, who was the representative of the Portuguese crown throughout the Pinhal episode, arrived in Macao only 15 days prior to Zamudio’s frigate anchoring in Piñal, putting him smack in the middle of the inter-Iberian conflict in the Far East.

In the ensuing months after Dasmarinas’ arrival, life on El Piñal was anything but perfect, with the Spanish unable to acquire a ship from Macao and the outpost’s inhabitants facing increasing hostility from the neighboring enclave. A letter sent to Dasmarinas by Francisco de Castilla, an El Piñal dweller on a reconnaissance mission in Macao, demonstrated that aggression towards the Spanish crew had reached new heights. Dr. Pinto quotes Castilla’s letter as stating: “I talked with the captain and he told me that, since your Lordship did not leave with D. Juan [Zamudio], they refuse to supply even water and they will try to harm you as much as possible.” Castilla goes so far as to write, “they would set you on fire.”

Although Dasmarinas had apparently fixed his frigate, he avoided the governor of Manila’s order to return from China. And by this time, the Portuguese in Macao had set up a full blockade of El Piñal.

Meanwhile in Macao, Dasmarinas and the Spanish had a small support group, namely the Franciscans and Dominicans. However, within the walls of the city, showing an inkling of support for their Iberian brethren on the neighboring port could have possibly cost them their lives. With growing pressure both externally and internally to withdraw to the Philippines, Dasmarinas and his men left El Piñal on November 16, 1600, with a frigate and a junk. However, in what could be noted as a blunder typical of Dasmarinas, the ships caught gnarly winds that sent them, once again, back on the South China coast. The frigate, which was in the better condition of the two vessels, was told to make way for Manila while the captain and part of his crew stayed on the junk, waiting for a better time to return.

The Spaniards took shelter on Lamapacau, a small island near Macao (the island has since become part of a larger island as sedimentary deposits bridged the gap). Although they were authorized to return to El Piñal by local Chinese authorities, Dasmarinas opted not to offend Macao with such an action, even attempting to make an informal agreement with Paulo de Portugal to compensate Macao by way of favorable trade in Manila.

Dasmarinas’ negotiations, though, did not bear fruit, and two months after he and his crew departed from El Piñal they were attacked by a heavily armed Portuguese armada from Macao. The volley lasted several hours, and killed an unspecified number of Dasmarinas’ crew. However, the surviving Spanish managed to flee from the Portuguese’s grip, taking shelter in the bay of Guanghai before eventually returning to Manila a short time later.

This spelled the end of Spain’s foray into China; although discussions were had in the following decades of a return to the port, none were ever followed through.

The year after the Spanish departure from El Piñal, a Dutch ship arrived off the coast of Macao, mistaking it for the former Spanish settlement. Under pressure from city residents, Paulo de Portugal signed off on the execution of 17 captive Dutchmen – a move that exceeded his own authority, since he required approval from the viceroy to enact such an order. The murdered Dutch explorers are viewed by many as the final act of the Pinhal episode, and the incident fundamentally changed the relationship between the Portuguese and the Dutch in Asia for the next 60 years.

The Hunt for El Piñal

It’s nearing noon when we board a bus in northeastern Zhuhai to take us to one of the alleged sites of the forgotten Piñal and it’s a swelteringly 34 degrees Celsius – perhaps hotter – in the unrelenting South China sun. Our destination: The lush and verdant island of Qi’ao, which is situated roughly 125 kilometers southeast of Guangzhou and just off the coast of Zhuhai.

Bridge linking Qi’ao Island and Zhuhai. Image by Ryan Gandolfo/That’s

Our fascination with the small island, which covers less than 24 square kilometers, can be traced back to a simple translation. In his 1983 book Fidalgos in the Far East 1550-1770, historian Charles Boxer notes the word ‘pinhal’ is the Iberian word for pinewood or a pine forest and that the term was often used by both the Spanish and Portuguese as a place name. Boxer’s work cites J.M. Braga, who identified El Piñal as “the anchorage of Tonkawan at Kumsing-mun on the east coast of the island of Chungshan (Heungshan).” As Professor John Newsome Crossley points out in Hernando de los Prios Coronel and the Spanish Philippines in the Golden Age, the island of Heungshan is today known as Qi’ao Island. To make matters more intriguing: The island is also known to have pine trees.

While, prior to setting out we are aware that the odds of finding something concrete to prove Zamudio and Dasmarinas had settled on this particular plot of land over 400 years ago is unlikely, the aforementioned narrative seems compelling enough to warrant investigation.

After arriving at the island’s northernmost bus stop, we wander over to a nearby bike rental stall to acquire transportation for our adventure.

“I was born here in 1982, so you can guess how old I am,” Lan, the shop attendant, tells us. After hearing the theory of the forgotten Spanish trading post that may once have called the island home, she responds matter-of-factly: “If you say so, it’s probably true. I wouldn’t know anything about that, but perhaps my parents would, they were born in the ’30s.”

We broach the idea of bringing up the topic with her parents, but she shoots it down and instead recommends visiting Baishi Jie. “There’s a memorial there in honor of the time that we resisted the British invasion in the mid-19th century. It may be of some help to you.”

The bike ride along Qi’ao Dadao is in many ways reminiscent of Florida’s section of I-75 that crosses the everglades and it’s the most direct course from the bike rental stall to Baishi Jie’s resistance memorial. After approximately five minutes of traversing the route, our journey is halted by the sight of a lone pine tree resolutely erected on a hilltop on the other side Qi’ao Mangrove Wetland Park.

Qi’ao island. Image by Ryan Gandolfo/That’s

Despite our best attempts to reach the tree, however, it is blocked behind a building surrounded by bodies of water. When asked about the tree, two security guards stationed nearby take on confused looks and state they know nothing about the towering piece of foliage. We hop back on our noble, two-wheeled steed and make way for Baishi Jie.

The memorial that Lan described is precisely where she said it is, and is proudly composed of a group of adults and children positioned behind a cannon – one of the men blowing a conch shell while holding a rifle. Beyond the commemorative site to imperial resistance is the old fort, where Qi’ao’s villagers successfully fended off British and American intruders on the island in 1833, prior to the First Opium War.

A sculpture commemorating Chinese fighters. Image by Ryan Gandolfo/That’s

It’s an impressive site, but it does little to answer our questions about the island’s possible connection to the Piñal story. Although the notion that other foreign powers ended up here just a century and a half after the Spanish departed gives Qi’ao another breath of life – there has to be more.

Professor Crossley notes that on the southeastern coast of Qi’ao Island there is what appears to be a grove of pine trees nearly 1 kilometer in length. He came to this conclusion based on analysis of Google Earth images, but it seems worthy of a visit regardless.

Roughly a 10-minute bike ride from the Baishi Jie memorial is a steep hill topped by a shaded pagoda. From the top, it’s a treacherous 10-minute descent down on foot. Nearing the base of the hill, we notice what appears to be several barracks and a tent with a prominent red cross. Just beyond that, the coastline is visible, and it isn’t hard to imagine 16th century Spanish ships anchored off the shore.

A decrepit tourist map along the route points the way to the sea and we forge on in hopes of finding the fabled pine grove Crossley spotted on satellite images.

Upon reaching a makeshift parking lot near the water, a voice calls out “Hey, you’re not supposed to be here.” A man in military fatigues informs us we’re not allowed to be in the area and he points us in the direction to leave.

That, unfortunately, is as close as we came to the pine grove of Qi’ao Island. We leave with no new revelations, but with a solid appreciation that the island – Spanish trading post or not – played a role in the imperial power struggles that plagued China until the dawn of the PRC.

Well, Where Is It?

While we only encountered a single pine tree on our visit to the island, according to multiple scholars, Qi’ao is – or was – home to numerous pine groves.

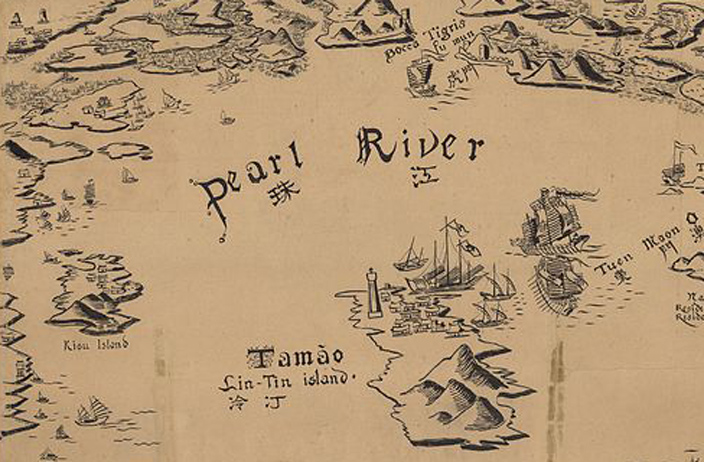

Jack M. Braga, a historian who once lived in the area, believed Qi’ao Island was the location of El Piñal because it is “the only place between the Bocca Tigris [the Spanish term for where the Pearl River and South China Sea meet] and Macao where a grove of pine trees has flourished for centuries, and it was also used by the English and American clippers of the early 19th century.”

Professor Crossley also added that “according to the Chinese Ming Dynasty records, El Piñal is an island. It, therefore, seems most likely that El Piñal can be identified as Qi’ao Island.”

Pearl River Delta. Image by Ryan Gandolfo/That’s

While scholars also argue that El Piñal could have existed near the mouth of Xijiang, west of Macao, there are reasons why this likely wasn’t the case. For one, settling west of Macao would have put the Spanish in a very isolated and vulnerable position, being further from Canton. Pinto points out that Paulo de Portugal didn’t attack Dasmarinas and his men until they were in Lampacau, which could possibly hint that El Piñal was closer to Canton than Xijiang.

The distance between El Piñal, Macao and Canton are also key factors. One particular knock against the theory that Qi’ao Island was the home of Spanish trade post: A 1564 map of the area places El Piñal 10 to 12 leagues from Macao and 20 to 30 leagues from modern-day Guangzhou, which would likely pin the site further north than present-day Qi’ao Island.

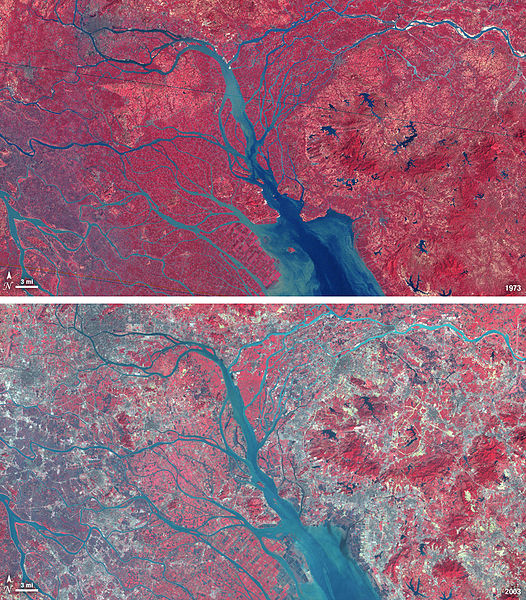

Of course, there is also the strong possibility that the original site of El Piñal is a casualty of the changing layout of the Pearl River Delta. Lingdingyang Bay, the largest estuary of the Pearl River system, has been changing since prehistoric times, and even more so in recent centuries as a result of rapid urban growth and rampant exploitation of marine resources, among other factors.

NASA satellite images showing the rapid changing layout of the Pearl River Delta from 1973-2003. Image via Wikimedia

NASA satellite images showing the rapid changing layout of the Pearl River Delta from 1973-2003. Image via Wikimedia

When we solicit Dr. Pinto’s thoughts on where he thinks the settlement might be, he responds, “My opinion is that El Piñal is a now-missing island between Macao and the Bocca Tigris.” And with the drastic changes to Lingdingyang Bay, including the diminishing surface water area and rising water levels, El Piñal may simply be lost beneath the surface.

For more Cover Stories, click here.

[Cover image via Wikimedia]

0 User Comments