Limehouse Causeway is a quiet, unremarkable street. Like much of London’s East End, it comprises a curious assortment of Victorian brick terraces and austere slabs of 1960s social housing.

At one end you'll find the DLR, a driverless metro built to serve the city’s once dilapidated docklands. At the other, a boarded-up pub lies victim to the rising rent that forces ten such establishments to close in London each week.

These symbols of gentrification disguise the area’s past as a foggy, filthy slum. And another part of the street’s heritage is absent from view: No plaque says it, but Limehouse Causeway was once the center of London’s immigrant Chinese community. A hundred years ago, this narrow street would have been lined with Chinese laundries, grocers and some of the city’s most notorious opium dens. The term ‘Chinatown’ was first applied to the area at the turn of the 20th century, though Chinese presence here dates back to the 1860s. As British appetites for tea, ceramics and silk grew, so too did trading routes to the Far East. Merchant ships would find cheap labor in Chinese ports, and the sailors would take rest in London before returning home.

The term ‘Chinatown’ was first applied to the area at the turn of the 20th century, though Chinese presence here dates back to the 1860s. As British appetites for tea, ceramics and silk grew, so too did trading routes to the Far East. Merchant ships would find cheap labor in Chinese ports, and the sailors would take rest in London before returning home.

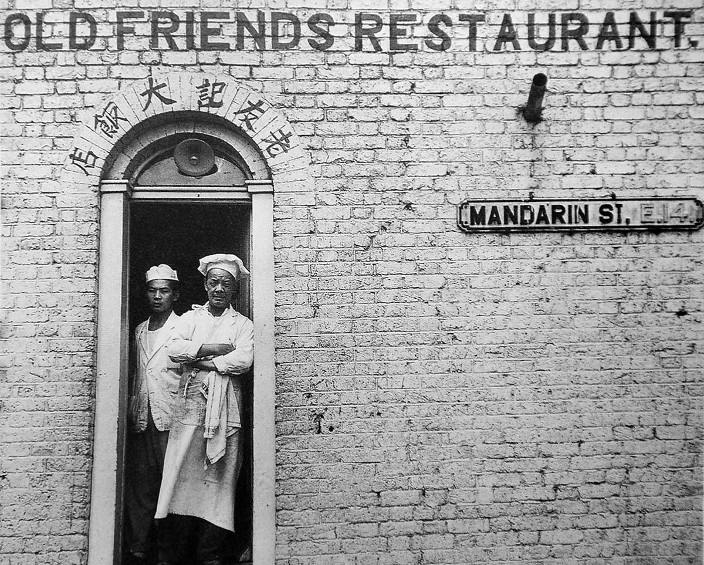

Limehouse’s population was therefore transitory, and made up, largely, of seamen. But these visitors’ desire for familiar home-cooked food (and a gossip in Cantonese) prompted Chinese businesses to set up shop. Behind legitimate storefronts lay not only opium sellers, but brothels and gambling rooms too.

Such depravity was, like most of the East End’s slums, considered an affront to rigid Victorian values. (The irony, of course, is that the British aggressively pushed opium in China while vilifying it as debauched at home.) But Limehouse was also seen as a burst of color in the otherwise drab docklands. Walls of Chinese stores were draped in red and orange paper, and in summer, brightly colored birds would sing in cages hung from high windows.  The smell of exotic foods also distinguished these streets from their neighbors. As this account from an 1895 edition of The Gentleman’s Magazine describes, a taste of China was readily available to Londoners:

The smell of exotic foods also distinguished these streets from their neighbors. As this account from an 1895 edition of The Gentleman’s Magazine describes, a taste of China was readily available to Londoners:

“The visitor to Chinatown finds cooking going on at all hours. This quite contradicts the common notion that the opium smoker never eats,” quips the author, who is identified only as J. Platt. “There is an opportunity for the inquiring stranger to sample not only the more homely fare, but also the most aristocratic.

“To the former, I suppose, belongs the cuttlefish, which in China takes the place the herring does with us. To the latter belongs first and foremost the well-known birds’-nest soup, the cost price of which to the merchant here is thirty-eight shillings a pound. Sharks’ fins, at fourteen shillings the pound, are another dainty dish to set before a king.

“I must confess that I never had the courage to attempt either of these delicacies. I have, however, partaken of the sea slug, or biche de mer. It is worthy of note that the most esteemed foods of the Chinese are all gelatinous.” No food is served on today’s Limehouse Causeway, gelatinous or otherwise. But walking up the intersecting Gill Street – another of old Chinatown’s main arteries – you'll soon reach one of the district’s three remaining Chinese restaurants, New Beijing.

No food is served on today’s Limehouse Causeway, gelatinous or otherwise. But walking up the intersecting Gill Street – another of old Chinatown’s main arteries – you'll soon reach one of the district’s three remaining Chinese restaurants, New Beijing.

Well, that’s its English name anyway. The Chinese characters read, loosely: “Big Dining Meeting Place.” And that’s exactly what it is. Like the shops of old Limehouse, this well-kept restaurant’s walls are painted in appealing shades of orange and dark red. Sure, there’s an obligatory waving cat, but it's otherwise free from the hackneyed pan-Asian paraphernalia found in most of the UK’s Chinese takeaway spots.

New Beijing’s menu nonetheless features all the Western-friendly classics one expects. Its “Most Popular” section lists crispy beef, roast duck with pancakes, chicken chow mein and other items adapted to British tastes. I begin with two mainstay appetizers, spring rolls and prawn toast (RMB34*), both of which I'd once considered to be the epitome of Chinese cooking.

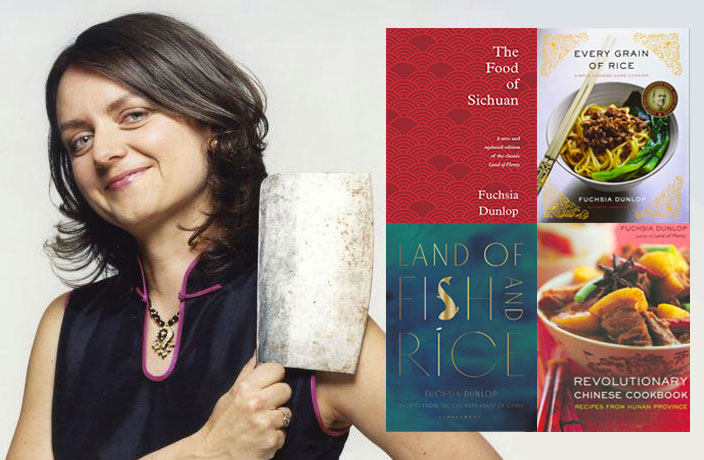

But New Beijing offers a couple of unexpected choices amid the archetypal takeout fare. I order the beef in Sichuan sauce (RMB67) and am pleasantly surprised by the tender meat and hint of spice.

It’s not exactly authentic, though. In fact, the dish is crippled by the absence of an ingredient rarely found in London’s Chinese restaurants: Sichuan peppercorns. The numbing spiciness, mala, is unique to Sichuan and Chongqing cuisine, and thus is alien to British palates (and stomachs).

Despite the apparent lack of peppercorns, the restaurant's Canto-British interpretations are nevertheless well-made. Then I speak with co-owner Eric Du and realize my grave mistake.  “You should have told me!” he says, upon learning that I live in Beijing. “I thought you were just a normal guy. We also have this menu.”

“You should have told me!” he says, upon learning that I live in Beijing. “I thought you were just a normal guy. We also have this menu.”

On it, printed in Chinese, are dishes one actually finds in China: century eggs, dry-fried green beans with chili, and cumin lamb from the Muslim northwest. Around half of Du’s customers are Chinese, and they’d settle for no less.

Yet, even with the restaurant’s Chinese custom – and its proximity to old Chinatown – there are no links to Limehouse’s past here. Du grew up in Beijing and only launched the business in 2015, although the premises have housed a Chinese restaurant for some time.

“I think it used to be called ‘Wonderful Chinese’ or something. I’m not sure,” says Du. “In 2001 there was a new owner, a Chinese-Vietnamese guy, and he changed it into a buffet restaurant called Wings Buffet. But it’s been a long time – it’s changed hands a few times.

“When we took over, I found that they weren’t making Chinese food to the right level. Local people preferred the buffet because the previous owner made it very cheap, but the quality and hygiene standards were a little bit under par. So we decided to change to a la carte – to offer people fresher, more authentic food, and special dishes from specific regions in China.”

If only I’d known. Never mind – my mistake seems fitting. The average visitor to old Limehouse would have experienced China through a Cantonese lens anyway.

As well as living apart from its British neighbors, the Chinese community was itself divided. Rival gangs clashed on West India Dock Road, the street separating the two communities. Today, the road hosts a tall sculpture of two dragons chasing one another’s tails. The memorial seems incongruous in a country where dragon slayers are more celebrated than the beasts themselves, but it’s the only formal recognition of this area’s Chinese past.

And less official reminders of the old Shanghainese quarter remain. Either side of Pennyfields, you’ll find roads called Ming Street, Pekin Street, Nankin Street, Canton Street, Amoy Place and Noodle Street.

Like the nearby New Beijing, Noodle Street is relatively new, having opened in 2010. But unlike the nearby New Beijing, this restaurant has embraced dishes from across Asia.

The reason, as our Vietnam-born waiter explains, is to help attract a wider crowd. “On weekdays, the queue goes outside the door – Canary Wharf is just there,” he says, referring to the nearby skyscrapers of London’s banking district.

London’s Chinatown in fact relocated to Soho in the 1960s. Demonized amid fears of criminality and deviancy in Limehouse (the area was no more dangerous than the rest of the East End, though the hysteric masses cared not for such truths), many left the area after the First World War. Those who tolerated the xenophobia would depart when Luftwaffe bombing practically flattened the district.

Meanwhile Soho, which was once populated by seedy sex shops and cabarets, has become one of the capital’s most exclusive (read: expensive) areas. Whether through fortune or foresight, the once vilified Chinatown has had the last laugh.

*All prices are rounded up to the nearest yuan, and are calculated using a post-Brexit exchange rate, giving all dishes the illusion of affordability.

Note: The third and final Chinese restaurant in the old Chinatown, Welcome Friends, was closed on both my trips to Limehouse.

0 User Comments