Behind a partition wall at the back of Shanghai’s World Expo Center, the scent of spray tan hangs in the air. Bronzed skin may be more commonly associated with rural labor in China, but in the world of bodybuilding (or jianmei yundong – literally ‘healthy and beautiful exercising’) it represents the final flourish in a quest for perfection. Flashes of bare soles and unfinished legs are the only traces of the paleness beneath.

While bigger international competitions offer spray booths for a more even coating, in the makeshift backstage at the International Health, Wellness and Fitness Expo (IWF), tanning spray is applied the old-fashioned way. Coaches smear it liberally onto their teams, which consist of toned women in bikinis and hulking men in skimpy regulation ‘posing suits’ (read: revealing colored briefs).

Once suitably bronzed, the competitors carry out some final exercises before proceeding to the stage. These last-minute pumps may add a little to the bulge of muscle. But for most of these athletes, the short walk through the convention center marks an end to months of preparation – and days of dehydration to achieve tight skin and highly visible veins. This is the first major competition after Chinese New Year, but all the competitors I ask say that they abstained from the traditional celebrations of dumplings and baijiu shots.

Amid the mass of human flesh, Taiwanese

bodybuilder Ady Kung strikes poses for fans

and photographers. Having just returned

backstage from his semi-final, the 35-year-old’s

smiling face appears utterly relaxed while

his body tenses in every way imaginable –

just as it had on stage moments earlier. He

replicates some competition stances, each

designed to show off different sides of his

freakishly muscular physique.

Amid the mass of human flesh, Taiwanese

bodybuilder Ady Kung strikes poses for fans

and photographers. Having just returned

backstage from his semi-final, the 35-year-old’s

smiling face appears utterly relaxed while

his body tenses in every way imaginable –

just as it had on stage moments earlier. He

replicates some competition stances, each

designed to show off different sides of his

freakishly muscular physique.

“I want to be a hero – I always wanted to be a superhero and to look strong,” he says of his decision to progress from powerlifting to bodybuilding 14 years ago.

Kung is calm, soft-spoken and as stoic as one might expect. He is “very confident” about his chances in the next day’s final. And with good reason. Having already taken part in five international-level competitions in his career – and with hopes of breaking into Asia’s top five this year – Kung was clearly among the best in his semi-final. Even to the untrained eye, his muscularity, symmetry and poise stood out on stage.

Should he succeed, a reward of RMB10,000 (USD1,500) awaits. Although top prizes at China’s biggest competitions can be up to eight times higher, the winners’ pot here at the IWF is still sizable given that competitors pay an entrance fee of just RMB100 (USD15). The majority of the prize money comes from sponsors looking for a slice of China’s growing interest in extreme fitness.

In addition to commercial events like this one, official competitions are becoming increasingly common, according to China’s national team coach, Ji Kaili, who I find backstage, deep in a crowd of scantily dressed competitors.

“There are around 10 national-level competitions a year,” she explains. “But if you include all the smaller ones at a provincial level, it will be closer to 50. That’s an increase of at least 60 percent in the last two years. The fitness market is peaking now, and people’s mindsets are changing.”

Nonetheless, the popularity – and standard – of bodybuilding in China cannot compare with Europe or the US, its spiritual homeland. As new competitions like Mr. Universe and Mr. America fascinated the West throughout the 1950s and 1960s, the sport was falling out of favor in China. Viewed as a Western pursuit and outlawed during the Cultural Revolution, bodybuilding was consigned to underground gyms until the economic and social reforms of the late 1970s.

But the sport developed rapidly thereafter. China founded its first formal bodybuilding competition, the Hercules Cup, in 1982 and joined the International Federation of Bodybuilding (IFBB) four years later. By 1994, Shanghai had been asked to host the World Championships, though it was clear that the country’s amateur athletes could not match their international counterparts. As American stars flew to China with lucrative sponsorship deals, one competitor, Chen Gin, cycled over 2,000 miles from Guizhou province just to take part.

A competitor performs some last-minute exercises before taking to the stage.

Today, China boasts its own homegrown world champions. Mainland competitors have won titles in the IFBB and the World Bodybuilding and Physique Sports Federation (WBPF). No-one in the bodybuilding world seems to know exactly how many athletes there are in China, but the WBPF’s secretary-general tells me it’s in the “thousands.”

At a semi-professional level, however, there would appear to be no more

than 100, none of whom live on prize money and sponsorship alone. (To do so

would require a significant sum – one athlete I speak to spends RMB10,000 a

month on high-protein food ahead of competitions.) Every competitor I meet has

another job in the fitness industry, many of them personal trainers. By contrast,

the number of full time professionals in the US is close to 1,000.

Mainland tournaments are also considered to be behind international standards. A number of athletes I speak to complain of backstage chaos at Chinese shows, with competitors left confused about when to go on stage, or told last-minute before they’re ready. But the IWF runs smoothly enough. There is even a small media center where I am introduced to one of the veterans of Chinese bodybuilding, Tang Jianyi.

Tang has been bodybuilding for the last 27 years. I offer him a seat on a white leather sofa, but he politely declines on the grounds that he may leave some of his tan behind.

“It’s getting better and better,” he says of the changes he has seen in bodybuilding since the 1980s. “More people are getting involved and the equipment is getting better.”

Despite being in his early 60s (I dare not ask his exact age after he grunts indifferently to my observation that he does well to keep up with younger competition), Tang’s toned, taut body is a caricature of masculinity. Like all of the bodybuilders here, it’s hard to understand how he achieves such an exaggerated shape through exercise and diet alone.

“I’m totally natural. I don’t use any steroids or medicines,” he says, pre-empting an awkward question. “This is my way – the natural, healthy way.”

Today, China boasts its own homegrown world champions. Mainland competitors have won titles in the IFBB and the World Bodybuilding and Physique Sports Federation (WBPF).

True, perhaps, though the same cannot be said for many in bodybuilding. Since the 1970s, the use of steroids and growth hormones has been the most open of secrets. It is prolific among the sport’s top competitors, and China appears to be no different. No-one seems to deny that steroids are found here.

But the caveat offered is always the same: Chinese athletes don’t use them properly. While there is debate on whether any steroid use can truly be considered ‘safe,’ certain practices – like giving muscles enough rest at the end of each ‘cycle’ – can reduce the dangers. As China arrived late to bodybuilding, coaches may lack the experience and education to mitigate the risks. While there was no evidence of steroid use among the competitors at the IWF, the question remains: How can Chinese bodybuilders compete at an international level without them?

***

The next day at the IWF, the finals are getting underway. Ady Kung and the competitors in his weight class prepare in a pen next to the stage, their tans still dripping. A huge man with a surgical facemask performs resistance exercises with a length of elastic, while others rub and slap their muscles in anticipation.

There’s no seating area for spectators. Instead, crowds pile against a metal barrier, climbing on gym equipment for a better view. The audience appears to be made up of curious onlookers rather than bodybuilding enthusiasts, though a small cheer rings out as the finalists are summoned for inspection.

Fans climb on gym equipment for a better view.

Once their number is called, each bodybuilder struts to the front of the stage to strike poses for a long table of judges. The accompanying music varies dramatically. One athlete emerges on stage to an orchestral anthem that crescendos as he reaches for the sky, biceps bulging. Kung, meanwhile, performs to Seal’s ‘Kiss From a Rose.’ It’s strangely emotive.

As all eight finalists line up beneath bright lights, judges ask them to perform identical poses in groups of two or three, rotating clockwise in quarter turns. All maintain smiles throughout; their muscles visibly shaking with strain. Their attempts to appear both tense and relaxed vary in success. Kung certainly seems composed, but others’ grins assume manic properties, their heads appearing as if photoshopped onto separate bodies (an illusion exacerbated by uneven tanning).

After about 10 minutes of comparison, the judges dismiss the bodybuilders. Kung’s confidence proves well-founded: he is crowned the winner shortly after, returning to the stage to collect his trophy and a brown envelope stuffed with cash.

Next up is a group of toned guys in board shorts. Known as ‘physique,’ this category focuses less on extreme muscle development and more on attainable – one might say ‘normal-looking’ – figures.

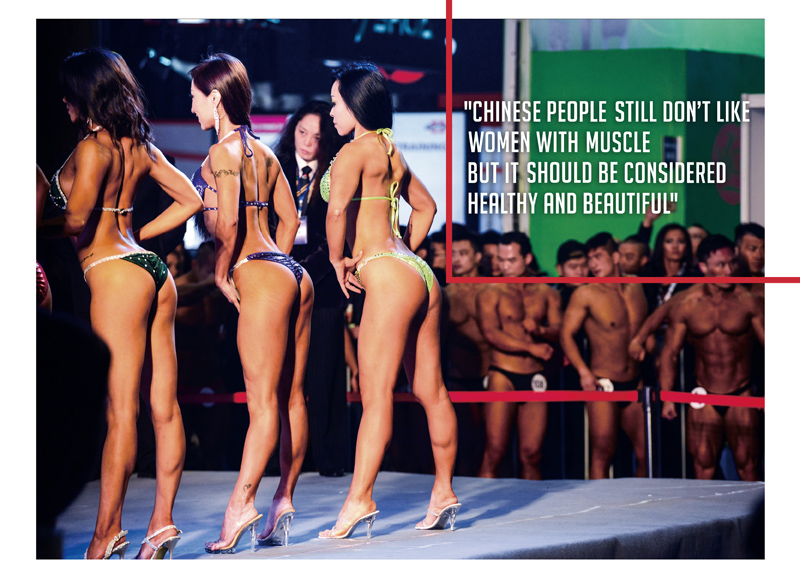

The crowd thins a little – extreme musclemen are the main attraction here. But in the women’s categories, it’s quite the opposite. The more accessible divisions (‘fitness,’ ‘figure’ and ‘bikini’) have proven more popular in China. The IWF doesn’t even have a traditional ‘bodybuilding’ competition for women, explains Head Judge Rocky Cao.

The more accessible divisions (‘fitness,’ ‘figure’ and ‘bikini’) for women have proven far more popular in China. IWF doesn’t even have a traditional ‘bodybuilding’ competition for women.

“Bikini is the most popular now because it’s the most accessible,” he says. “People, especially in China, prefer women to be more fit and feminine. Bodybuilding for women got cancelled because it’s too muscular – you couldn’t tell if it was a guy or a woman at all.

“For bikini, the judge needs to see that you’ve trained and have a healthy diet,” he says, explaining the criteria he’ll be looking out for. “You have to be thin, but not as lean as the physique athletes.”

As the bikini athletes prepare for their final, a larger audience forms once more. Spectators hold phones and iPads aloft. By the competitors’ entrance, an old man with a long-lens camera (and no visible media pass) takes snaps of the women as they warm up in the pen.

Each finalist sports a sparkling bikini, faultless makeup and – as regulations stipulate – high heels. Like the male bodybuilders, each competitor is called to the stage individually before posing in groups for comparison. The positions they are asked to assume focus less on muscular strength and more on tone and outdated notions of femininity. But many in the sport say that these less extreme categories (and more achievable body shapes) make fitness competitions more appealing to women.

Two-time national champion Lulu Zhu is a case in point. She’s not competing at the IWF, but she’s here to meet friends and watch the contest. Zhu used to have a desk job at a jewelry brand before becoming more serious about fitness two years ago.

“I was going to the gym quite regularly, and I had some friends who said: ‘come and try a competition,’” she explains. “I started to like fitness more than luxury things – it’s more valuable. So I quit, and now I work in fitness full time.

“I do personal training at the same time. I have some female clients whom I help to achieve their goals and I’m also a master trainer, which means I give classes to personal trainers to help them get certified.”

The eventual winner of the bikini division, 34-year-old Jennifer Zhang, has a similar story. As a first-time competitor, she found the competition to be a natural progression from her fitness regime.

“I started at a gym,” she explains backstage. “I trained every day and started to get the benefits from the training. I built up my body, felt good and had a good shape. Last year my trainer asked me if I was interested in joining this competition and I thought ‘why not?’”

“For bikini it’s the whole package,” Zhu explains, when I ask about the differences in judging between men and women. “You’ve got to have a good body, but you’ve also got to have a good face, make up, hair, skin – you’ve got to show people your definition of being beautiful.”

The female competitors are certainly in excellent shape. They too have undergone months of preparation – diet, exercise and dehydration – for the show. But unlike the men’s division, there is something overtly flirtatious about the hair flicks, pouts and playful smiles required to win the approval of the judges (almost all of whom are men). There is a quiet but audible ‘whoop’ from the crowd when the competitors are asked to turn their backs and stick their butts out.

There is something very uncomfortable about this asymmetry of expectation between male and female categories. While the former are encouraged to achieve extreme levels of strength, the latter are celebrated for their femininity. But the message from all in the sport is clear: There is no appetite for traditional female bodybuilding in China. The national team coach who I’d met the day before, Ji Kaili, nonetheless hopes that the more muscular forms of women’s competition take off in China.

“Chinese people still don’t like women with muscle,” she says. “It should be considered healthy and beautiful. That’s why we need more media attention for girls working out. But it’s going to be quite hard – not just in China, but worldwide.”

Everyone at the IWF seems keen to stress that this is not just a Chinese phenomenon. Indeed, the bikini division was only introduced into China two years ago, while the worldwide move toward feminization in female bodybuilding has been underway since the early 1990s.

In 1992, the IFBB created rules stating that female competitors shouldn’t be “too big,” steering judges toward a more feminine physique. Eight years later, the chair of the judges committee, James Manion, wrote to all IFBB competitors telling them that women would be judged on healthy appearance, face makeup and skin tone. He concluded with the criteria: “symmetry, presentation, separations, and muscularity BUT NOT TO THE EXTREME!” (his capitals). Then, in 2005, the IFBB introduced a ‘20 percent rule’ that requested female athletes in a number of categories decrease their muscularity by a fifth.

***

The uneasy differences between male

and female roles in bodybuilding stem

not from the competitors themselves, but

from the judging system. Much of this

trickles down from the upper echelons

of the sport, though there are specific

problems that arise in China.

I meet competitive bodybuilder Lisa

Liu at her studio in Beijing. In addition to

running her business as a gym photographer,

she is one of the country’s most

successful fitness athletes. Having gained

sponsorship from a supplement brand,

she trains for four to five hours a day and

can bench press 100 kilograms.

One of China's most successful fitness athletes, Lisa Liu.

“Judging in China is below par,” she says. “The bikini contest is more about beauty than muscles. As long as female contestants look beautiful and skinny, judges think they’re great – even if they don’t have muscles. A woman I know is a pole-dancing teacher, who never spends time building up her muscles, but she does well in competitions every time because she’s beautiful.

“In China, fitness athletes are like swimsuit models, 90 percent of whom don’t have much muscle to speak of. If they entered international competitions, they would be knocked out in the first round.”

Her latter judgment may be unduly harsh. While it is clear that few Chinese competitors are globally competitive, an increasing number (including Lulu Zhu, whom I met at the IWF) are placing well at international-level competitions.

But Liu is not alone in her criticism of judging in China. One male athlete, who speaks to me on condition of anonymity, says that judges are affiliated with bodybuilding teams, and that it is almost impossible to win without joining one.

“It’s very political. Judges have stakes in gyms and they want their athletes to win so they can increase their fees for personal trainers,” he says, pointing to other commercial interests, like equipment businesses and supplement lines.

The athlete tells me that he once entered a contest independently and placed lower than he – and fellow entrants – expected. After joining a team, he secured a second-place finish, which he feels would have otherwise been impossible.

At the IWF, Head Judge Rocky Cao had been adamant that team membership makes no difference.

“Whether you’re on a team or on your own, the judges are fair to the athletes,” he told me. “Some might belong to a big team but the judges used to be athletes – they know what it feels like to be treated unfairly. So they are trying their best to just judge how the competitors look on the stage.”

Bodybuilding has always been shrouded in controversy. Steroid use, gender inequality and the dangers of extreme fitness have long been talking points in the sport. But the growth of these competitions in China reflects something very positive: the increased interest in health and fitness. Extreme fitness may be a niche pursuit, but it is symptomatic of a wider gym culture. One suspects that as China grows stronger, so will its bodybuilders.

Photos by Holly Li

0 User Comments