Upon boarding the K1082 in Urumqi it becomes apparent that – like many procedures in China – there’s no protocol for foreigners. Having initially let us pass, the old conductor changes his mind.

“Make sure their passport numbers are on the tickets,” he tells his colleague, calling us back.

“Where’s the number?” the young man asks, clearly unfamiliar with our documents.

After much page-turning we’re admitted for a second time. Our narrow, doorless compartment contains six bunks, each barely wider than the average human. Like all of China’s ‘hard sleeper’ carriages, the beds are stacked in threes – a spacious lower bunk, a smaller middle one and a cramped top bunk requiring great dexterity to reach. The compartment is equipped with a small table and a grubby square window from which to watch China go by. For the next 68 hours and 19 minutes, this is home.

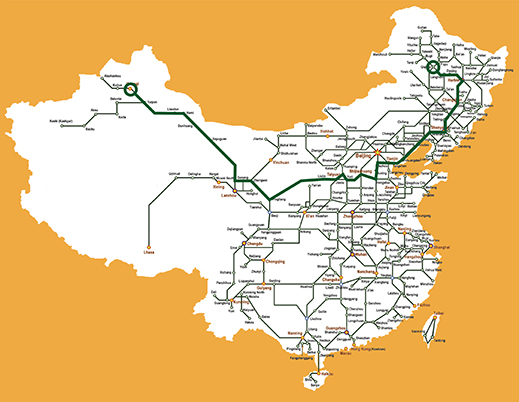

Currently the country’s longest domestic rail service, the daily K1082 meanders from the deserts of Xinjiang in the northwest (Xibei), to Qiqihar, an old garrison city in China’s freezing northeast (Dongbei). It stops 41 times along the way. At 4,687 kilometers, this isn’t quite the longest journey by distance – that title goes to the Z266 from Guangzhou to Lhasa. But through a combination of its leisurely pace and scheduled stops of up to 30 minutes, this route takes half a day longer.

These trundling trains seem hopelessly outdated. Their iconic dark green carriages may have once been the epitome of modern transport (the ‘K’ in K1082 stands for kuaisu – a ‘fast’ service), but they feel like relics in a country where almost 1.5 million people travel by high-speed rail every day. The dining cart is decorated in faded faux-velvet. The toilet is a glorified hole above the rails. There are even “smoking rooms,” though they are little more than wall-mounted ashtrays in the iron purgatory between carriages.

Yet, this is an affordable essential for many in China – especially in the west, which remains largely untouched by high-speed rail. Our three-day trip costs less than RMB800 per person, about half the price of the equivalent indirect flight. In fact, far from being phased out, the old rail network is constantly evolving for an increasingly mobile nation. The K1082 only became the longest journey last year after the route was extended in both directions.

A stretch of the Lanzhou-Xinjiang Railway, which runs from Urumqi to Gansu province

It is not, however, a popular train for tourists. As such, there’s a certain amount of interest in our arrival. Passengers from the neighboring compartment gather round to find out more. A slight man with thinning hair and brilliant hazel eyes hands us a foreign banknote with a one-word explanation. “Hasakesitan,” he says – ‘Kazakhstan’.

I’m not entirely sure what he expects us to say – he’s from Dongbei, not Kazakhstan. We politely examine the note and return it to him, enquiring about his destination. Like everyone we meet, our neighbor’s journey is one of necessity. Having been in the far west of China building agricultural silos, he’s returning home to deal with “family issues.”

The K1082's route and China's railway network

The K1082 departs without fanfare at 10.23pm, slowly winding to life on the short journey to Urumqi’s second station. Here, more passengers join. The old train conductor, Mr. Li, assures us that the carriage will fill up. And having checked the new arrivals’ tickets, he comes over to examine us. (The other half of the narrative ‘us’ is my full-time girlfriend and part-time translator, Nancy.)

Conductor Li is bursting with questions. After ascertaining our nationalities, our Chinese zodiac animals and the comparative cost of train travel in the West (“very expensive!”), he informs us that the lights will soon be turned off. The crowd disperses.

Dressed in a smart navy blazer embellished with gold buttons, Conductor Li will become our friend, guardian and one of the few people accompanying us from start to finish. With a wide, kind face and youthful eyes, he is inquisitive to the point of downright nosiness. Seeing the glare of my iPad later that night, he enters our dark compartment and bends down to inspect the screen.

“I’m reading a book,” I whisper.

“You can’t sleep,” he observes, wandering off.

He’s quite right. As we labor through Xibei, a low rattle sends creaks through every fixture. Multiple layers of sound, from deep shudders to high-pitched squawks, converge into a cacophony of arrhythmic mechanical noise and miscellaneous juddering. Trains speed past in the opposite direction; snores float through from neighboring compartments; railway staff, on permanent patrol, slam doors at either end of the carriage.

We screech to a halt at three stations on the way across Xinjiang. At one point I awake to find a new passenger – a thin, graying man in a purple sweater – hovering in our compartment. Despite his advanced age, the man nimbly ascends more than two meters into the top bunk, letting out a small burp on the way.

Morning breaks and I am roused, ironically, by an insipid cover of ‘The Sound of Silence.’ The occasional and indiscriminate broadcast of music – be it sweeping Chinese love songs or thumping Eurodance – will be a recurring theme of our journey.

We’ve reached Gansu province, and the frosty Xinjiang wilderness has transformed into a bare, brown landscape punctuated by electricity pylons. Parched mountains lie beyond the expanse, their facades adorned with prickly, otherworldly shrubs.

An old train works its way through Gansu province in winter

A pair of policemen arrive, their uniforms emblazoned with the word ‘SWAT.’ The title proves to be somewhat aggrandized, though they examine our documents with great seriousness. Staring intently at various pages of my passport, they confirm my suspicion that most authorities are unsure what to look for.

“Ah, Helan,” one says eventually, mistaking my surname – Holland – for my nationality. He seems satisfied.

They proceed down the carriage, which has rapidly come to life. The air fills with chatter and the cracking of sunflower seeds between molars. Vendors begin their rounds, alerting passengers to the availability of dried blueberries, boiled dumplings, lukewarm beer and instant noodles – the lifeblood of Chinese trains (you’re never further than 10 meters from a hot water tap).

The corridor of our carriage aboard the K1082

Passengers are quick to feel at home. Many come armed with their own slippers, and I am reminded of a description by American journalist Paul Theroux from his book Riding the Iron Rooster. Traveling across the country in the 1980s (a time when hard sleepers were the only option for those without guanxi – connections), he describes the atmosphere as: “a great sluttish pleasure for everyone – a big middle-aged pajama party, full of reminiscences. [The passengers] liked smoking and slurping tea and playing cards and shuffling about in their slippers – and so did I.”

Trains have certainly evolved since Theroux’s travels. Each carriage now comes equipped with charging points and Wi-Fi, though the former are rarely available and no one can make the latter work. But in many ways, much has stayed the same. Passengers share portable phone batteries rather than copies of People’s Daily, but the old sense of camaraderie endures.

Consequently, occupying a bottom bunk is to implicitly accept that it is public property – during waking hours, at least. The phantom in the purple sweater descends from his bunk and sits on the bed opposite. Our neighbor with the hazel eyes drops by for a chat, and our compartment is quickly engulfed by conversation.

Overseeing proceedings is Conductor Li’s younger colleague, a surly northerner with a Caesar haircut, who regularly gazes out of the window like a despondent puppy. He tells us that there are 40 staff members on the train: two conductors per carriage, five dining personnel and two drivers who switch shifts every eight hours. Having worked this route for more than a year, the young man is unable to name anything he likes about it.

The young train conductor rests in our compartment

“It doesn’t mean anything,” he reflects. “Nothing happens.”

Then, eventually, a glimpse of positivity: He’s from our terminus city, Qiqihar. This means that after six days on the train – three in each direction – he’ll be given a further six days to relax at home.

Never one to miss a chitchat, Conductor Li arrives, making himself comfortable on my bunk. When not checking tickets, his job appears to consist of cleaning floors, collecting trash and finding out how much our electronic devices are worth.

“How much did that camera cost?” he asks.

“I can’t remember, I bought it years ago,” my girlfriend replies.

“Just estimate,” he says, before embarking on a series of further price requests and friendly questions – about our work history, our families’ cars and the size of my salary.

A woman selling hot dogs rolls past and asks if we have any foreign money. Her currency collection spans 42 different countries, and she is thrilled that we have US dollars and Danish krone to contribute. Insisting on paying the going rate, the beaming woman hands over some hot dog earnings before parking up her trolley and falling into conversation about exchange rates and her admiration for Angela Merkel.

And so life on the slow train unfolds. Conversation moves from the compartments to the corridors and back again; window blinds rise and fall; people drift in and out of sleep.

The westernmost point of the Great Wall of China in Jiayuguan, Gansu

Scenery flies by at a similarly slow pace. There is commotion as we pass the westernmost point of the Great Wall, but otherwise, fellow passengers find the backdrop largely unremarkable. This part of Xibei is vast and empty, save for the occasional wind farm and a few railway signals lodged into scrubland. As we venture deeper into Gansu I am struck by its unerring brownness. This part of the world is oddly beautiful, but Hazel-Eyes doesn’t understand the appeal.

“Why are you taking pictures of the desert?” he asks. “There’s nothing there.”

This reaction is becoming familiar. No one quite understands why we’d travel this route for fun, and their response is often the same: “You should have gone south – it’s much more beautiful.”

Watch below: (VPN on):

Under the cover of darkness, we pass through Ningxia and Shaanxi (the province with two a’s). I awake in Lüliang, a modestly-sized city in Shanxi (the province with one a). We’re in coal country, and the land is becoming markedly busier the further east we travel.

Even in rural areas, there’s more to see than yesterday: industrial plants, cooling towers and signs of China’s uninterrupted construction boom. We see clusters of tower blocks being built in the unlikeliest of places. We see brutalist architecture and mock European spires. We see unfinished bridges that will one day carry trains much faster than our own.

By the second morning, life has taken on new rhythm. Our six-person berth has been completed by a driving instructor from Liaoning, a burly woman headed to Harbin, and a wispy youngster who eschews our social precedent by putting in headphones and reclining with his eyes closed. I’ve adjusted to the microclimate, growing indifferent to the wafting odor of smoke and the galling music that returns with vengeance at 8.55am (the exact time that an optimistic vendor marches past selling “beer, baijiu”).

Conductor Li checks in on us, clearly enjoying the novelty of foreign passengers who are semi-literate in China’s ways. He is fond of us – as we are of him. Taking a seat, he starts flicking through my copy of Time.

“I’ll have a look but I can’t understand English,” he muses, turning to an article about Donald Trump. “He’s 70 – he can’t serve two terms. Seventy-eight will be too old!”

After enquiring about my facial hair, Conductor Li asks whether I can tie a necktie. Then, without warning, he removes his and hands it to me, revealing that he himself cannot. This adds pressure to the recollection of a skill I rarely use. With the whole compartment (and various neighbors) watching, I produce something I believe to be a Double Windsor. He inspects it – his reaction utterly indecipherable – and ambles off again.

An afternoon lull descends as we’re plummeted into darkness by a succession of tunnels. The name ‘Shanxi’ means ‘West of the Mountains’ – and we’re headed east.

Walking to the end of the train I find passengers in various states of consciousness. Our carriage has quieted down with the new arrivals, who seem more guarded than the initial, inquisitive bunch. The man in the purple sweater regularly disappears for long naps, and seems to never do much else. He doesn’t play with his phone, read or – given that we always refer to him, privately, as the ‘man in the purple sweater’ – change his clothes. He just sits and stares pensively out of the window.

The man in the purple sweater looks pensively out of the window

The young man on the opposite bunk has yet to utter a word. Wearing thin glasses and a T-shirt emblazoned with the English words ‘An Idea Tree,’ his angular chin and premature grays belie otherwise boyish features. With more than a day to go, we have little choice but to engage him.

Shy at first, the softly spoken student proves receptive. Going by the name Xiao Yan (‘Little Yan’), he’s returning to university in Changchun, one of Dongbei’s industrial hubs. The journey would have been twice as fast by high-speed rail, but schedules didn’t work out that way.

Like many of China’s digital natives, Yan is staking his future on software development. After graduation he wants to find an internship developing mobile apps. We talk about social media, computer games and the Fast & Furious franchise – a selection of topics familiar to most of China’s post-90s generation.

Little Yan (left) and the driving instructor bond over technology

After hours of silence, Little Yan now seems liberated. Soon he has struck up an unlikely friendship with the Liaoning driving instructor. They make an odd couple – a diligent student who learned to cook for his parents aged 12, and a boisterous 40-something who I’d earlier spotted looking at bikini babes on his phone. Yet, their interaction is brotherly and, at times, hilarious.

“I find it impossible to gain weight,” Yan complains. “I eat and eat but I don’t grow.”

“You’re so dumb!” replies the driving instructor. “You’re just too young to put on weight. When you’re my age you can’t stop. Wait until you’re married. My wife makes so much nice food – that’s what makes you fat,” he claims, overlooking the fact that his job involves sitting down all day.

As with so many of the day’s exchanges, we’ve landed on the topic of food. It is a subject of universal interest in China – just as weather is to the British. The best dishes of any given province are fertile grounds for conversation, often accompanied by demonstrations of how they’re best eaten. So as the sun sets on our approach to Tianjin, talk invariably veers towards the city’s gastronomic delights: goubuli baozi, literally ‘dogs don’t pay attention stuffed buns,’ and jianbing guozi, a unique take on the fried pancake.

With a seven-minute wait at Tianjin station, the driving instructor rushes out to the platform, returning with two boxes of the steaming buns. He passes them out among our newly cemented six-person group. Little Yan, clearly serious about gaining weight, grabs the most.

A snack vendor awaits on the platform

Good spirits continue into the night. At one point the driving instructor introduces us to his wife on a video call. I feel a new loyalty towards – and trust for – this adopted family. Our inescapable proximity to one another breeds familiarity, and that familiarity erodes awkwardness and any qualms about leaving valuables unattended. In this sense, life on the slow train is much like life in a big Chinese city. Your immediate neighbors’ business is innately your own. As for everyone beyond? Far less so.

At the beginning of our journey, Conductor Li had told us that “lots of people” would travel the full length of the route from Urumqi to Qiqihar. But they’re in other carriages, so we’ll never know.

Unlike a real family, ours is inherently temporary. I awake on the third morning (my alarm is once again ‘The Sound of Silence’) to find the driving instructor’s bunk empty. He departed in the night, and we hadn’t even got around to asking his name.

Deeper into Dongbei, the landscape becomes decidedly more agricultural. Come summer these fields will heave with yellow corn, the staple crop of this region. But for now they are wide, flat and dead. The countryside is instead dotted with dried streams and frozen ponds. (“Do you also farm the fields in the West?” Conductor Li later asks.)

The sun sets over Heilongjiang, in China's far northeast

For the first time, the journey feels grueling. Whether a result of close living conditions or our instant-noodle diet, my throat is scratchy and dry. I feel new sympathy towards those for whom this isn’t a choice. I feel even greater sympathy for passengers of the old Shanghai-to-Urumqi train which, before the completion of the Nanjing Yangtze River Bridge in 1968, involved a ferry and took 101 hours and three minutes.

Over the course of our final day, we cut through the cold heart of Dongbei: Shenyang, Changchun then Harbin, a far-northern city famed for its yearly ice festival. There is a sense of finality about this stretch. People drip away and aren’t replaced – first Little Yan, then Hazel-Eyes and the man in the purple sweater (he’s still wearing it as he bids us farewell). Finally, the burly woman departs at Harbin – along with most of the train’s staff – leaving us with a warm smile and a box of small, uneaten cucumbers.

Despite being hours from our destination, Conductor Li strips the beds. Food carts trundle by, though they’ve been ravaged to near-emptiness. The woman peddling dried blueberries expresses delight at having sold every last pack.

Little Yan and the blueberry-seller

It’s like being the last people at a party. And with neither travel companions nor bedding, we’re left to sit on the hard bunk and absorb this immense and remote part of China. In its final hours, the K1082 passes through vast expanses of icy brown, drifting from one infinite nothingness to another. I could easily come to the hackneyed conclusion that we’ve seen more of China inside the carriage than outside the window. But given how brown the country’s north is during late winter, it’s hardly a fair comparison.

Heading into Qiqihar, the horizon fills with nodding pumpjacks lifting oil from deep wells. Conductor Li stops by for a debrief. Irritated by the music, he hits a switch and instantly kills the sound in our compartment. If only I’d known.

We ask him what he’ll do with his six days off.

“Oh, just cook and clean,” he says, bouncing a question back to us. “Do you have somewhere to stay in Qiqihar?”

“We’re actually flying back to Beijing tonight. We just wanted to ride the train.”

His reaction is one of amused incredulity. But there’s also a flash of pride that two foreigners might find his train so interesting that they’d ride its length for no reason other than to see China’s great north.

Images by Nancy Tong & Wang Wei; Graphics by Iris Wang

0 User Comments