Walking along Tokyo’s affluent Omotesando Avenue or Aoyama neighborhood today, flagships of world-renowned Japanese fashion labels like Comme des Garçons, Issey Miyake and Yohji Yamamoto proudly brush shoulders with the likes of Prada, Dolce & Gabbana and Marc Jacobs. Here, people on the streets are effortlessly chic, with an understated sense of style that seems part of the Japanese DNA. But in reality, Japan’s ascension to a major global player in fashion only happened a few decades ago.

Originally from Pensacola, Florida, writer W David Marx has been living in Tokyo and writing about Japanese pop culture and fashion since 2001. On his first trip to the city in the late 90s, the Harvard University East Asian Studies graduate saw a similar scene on the streets: “People were just wearing the right t-shirts, jeans and sneakers,” he recalls of the moment he first witnessed Japan’s obsession with style.

Ametora author W David Marx

Marx’s 2015 book, Ametora: How Japan Saved American Style, is a historical account of the assimilation of American traditional fashion, exploring how the Japanese adapted and ultimately perfected it, subsequently turning this newly-honed comprehension of the style into huge global success stories like Uniqlo, Evisu, Kamakura Shirts and more. Besides the American traditional ‘Ivy League’ look, Marx also delves into denim, military wear, streetwear and beyond.

“When people talk about [postwar] American culture and fashion in Japan, they just assume that it all started at the end of World War II during the American occupation – the army showed up, and the Japanese people idolized and adopted everything American – but there was actually a lot of conflict along the way,” Marx explains when we met at a speaking engagement in Shanghai.

While previous literary discourse has taken a micro approach to the subject, dissecting the intricacies of clothing patterns and designs, in Ametora (an abbreviated and anglicized word in Japanese for American traditional style) Marx examines the topic through a sociocultural lens, investigating how and why businesspeople and trendsetters brought these styles to Japan. Ultimately, Marx attempts to reveal what effects the “absorption of American style had on the Japanese identity.”

Ametora: How Japan Saved American Style

“[Prior to] 1965, few Japanese men dressed like Americans,” Marx says. “Someone had to come in with commercial motives to create an industry around American fashion.” That someone was Kensuke Ishizu (1911-2005) – the man responsible for kick-starting Japan’s decades-long obsession with American fashion, when he introduced Ivy League-style outfits to the youth of his home country in the 1960s.

Ishizu’ s life and work is the focus of the first few chapters of Ametora. Born into a wealthy family from Okayama in western Japan, Ishizu spent the early part of his fashion career in China during World War II. With the ongoing war efforts disrupting his family's paper-making business, the 28-year-old Ishizu moved to Tianjin in 1939 to work as the sales director for a major Japanese department store, Okawa Yoko, where he also ran the menswear department.

Tianjin, for the most part, was not really affected by the Japanese invasion and violence happening elsewhere in China. “While most of the folks back home were wearing cotton khaki uniforms, Ishizu wore Western suits and stayed in this British-style mansion in Tianjin; he was basically living the playboy life,” Marx says.

Ishizu spent his days learning the trade from British expat tailors, immersing himself into the city’s wider international community of Italians, Jews and Russians. However, things took a turn for the worse after the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, leading the Okawa Yoko management to sell off their assets in 1943.

Kensuke Ishizu (top left) in Tianjin with Russian friends

Left with a modern day equivalent of USD27 million in severance, Ishizu chose to remain in Tianjin. But after Japan’s defeat in August 1945, the former menswear expert was locked up until the US 1st Marine Division arrived, and a young Lieutenant named O’Brien released him to perform translation duties. The two men became good friends, and it was the Princeton alumnus who regaled Ishizu with stories about American Ivy League campus life. Ishizu's comfortable seven-year tenure as an expat in Tianjin came to an end in March 1946 when the Americans sent him and his family on a cargo ship back to Japan, leaving behind the massive fortune from his payout.

With his hometown bombed into piles of rubble by the Americans, the only way for Ishizu to earn a living was for him to go back to his old trade – menswear. “Ishizu’s exposure to Western fashion culture in Tianjin, though a somewhat questionable interest during the war, gave him a massive advantage over his fellow countrymen,” Marx says. “He had both knowledge and experience of making Western clothes, and knew the right way to wear them.”

By 1950, seeing the return of the market for luxury goods as the Japanese economy began to recover, Ishizu established VAN Jacket, a clothing brand that could provide middle class consumers with ready-to-wear products as a cheaper alternative to tailored suits, which were a luxury only the elite could afford.

"When people talk about [postwar] American culture and fashion in Japan, they just assume that it all started at the end of World War II during the American occupation... but there was actually a lot of conflict along the way"

Met with a lukewarm reception from older adults for his first products and desperate for inspiration, in 1959 Ishizu visited Lieutenant O’Brien’s alma mater, Princeton University. It was here that Ishizu found what he needed: Ivy League fashion. Blazers, neckties, Oxford button-down shirts, flannel pants, all made with durable materials like cotton and wool. Ishizu sensed that these were things that suited the tastes (and budgets) of a younger audience back home.

Upon his return, Ishizu enlisted the help of his son Shosuke, who was working as an editor at a menswear fashion magazine Men’s Club and his colleague Toshiyuki Kurosu (an avid Ivy League clothing fan) to head up VAN’s planning department. By 1962, its first ‘Ivy line’ was born. To market the concept of Ivy League clothing to a Japanese audience, the team turned to Men’s Club for some free PR. Kurosu started an ‘Ivy Leaguers on the Street’ column in 1963, and fashionable teens flocked to the streets of Tokyo’s hipster conclaves wearing Ivy League clothing with the hopes of being photographed. By the summer of 1964, just before the opening ceremony of the Tokyo Olympics, an estimated 2,000 Ivy fans dressed up and congregated in Ginza’s Miyuki Street each weekend.

Dubbed the ‘Miyuki Tribe’ by conservative media, who saw the style as a symbol of juvenile delinquency, the police stopped “anyone in a button-down shirt and John F Kennedy haircut” and arrested 200 youngsters with misdemeanor charges on a September evening. Though the Miyuki Tribe disappeared from Ginza after the incident, for progressive teens across Japan, the national attention on the raids created a cool factor around the Ivy League aesthetic. Perversely, the style of quintessential WASP-ish elitism and tradition in America had become an emblem of youthful rebellion in Japan.

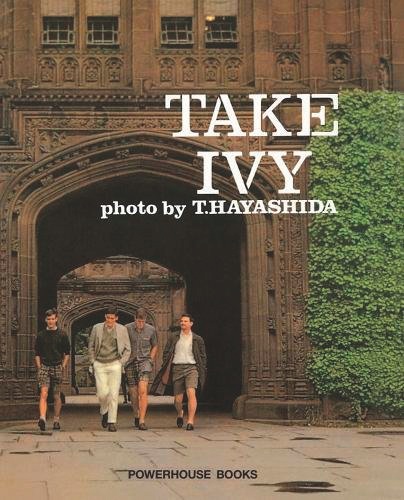

The English version of Take Ivy

“The word ‘save’ has two meanings,” says Marx, referring the subtitle of his book (How Japan Saved American Style). “The first is to ‘preserve,’ and Take Ivy [a fashion photography book documenting the attire of American Ivy League students during the 60s] is a good example of it.” In 1965, sensing a need to clear the stigma associated with the Ginza raid and to educate the public about Ivy League fashion, Kensuke Ishizu funded a team of VAN and Men’s Club employees to fly to the US to create the photo book and documentary film, based on what they saw at Ivy League university campuses.

American college students in 1965 (Photo: Amazon.com)

Though Take Ivy was met with a lackluster response during its initial release, it would eventually gain a cult following in 2008 when fashion writer Michael Williams posted scans of the book on his website, A Continuous Lean. In 2010, Take Ivy was translated into English and rereleased. Brands like J Crew, Gap and Ralph Lauren flocked to it, using it as shelf displays in stores and even drawing design inspiration from it.

“Another meaning of ‘save’ is the idea that the Japanese somehow ‘rescued’ the American traditional style,” Marx explains. “When the style was back in vogue again during the late 2000s, it was the version with a Japanese twist that had gone global, not the classic American form from decades ago.”

“The main thing to understand from the rise of Ivy style in Japan during the 60s is that the young Japanese people weren’t just blindly copying the Americans; they were reading about these styles from Japanese magazines edited by Japanese people, and buying clothes from Japanese brands.” This relationship between brands and media became a model that foreshadowed how the Japanese would receive and consume the latest news on fashion and trends for the next five decades.

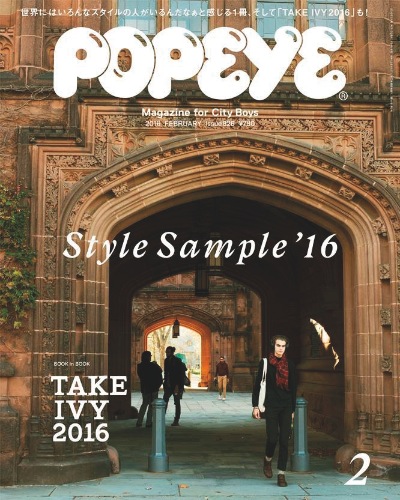

Popeye's Feb 2016 issue pays tribute to Take Ivy

With the rise of fashion publications like Popeye in the mid-70s (a magazine that Marx contributes a monthly column to), Marx asserts that ‘catalogue magazines’ became authorities on what to wear and where to shop for the Japanese. “Social media and blogs have become more prominent in recent years, but in terms of legitimacy, magazines in Japan still have this aura… people just believe in their editorial eye and trust their aesthetic.”

When asked about his take on the relationship between the Chinese and Japanese fashion scenes, Marx notes, “I think China is still quite brand status-oriented, while Japan is no longer a logo-driven market; people would read more into the texture of the fabric and other details. People from the Greater China Area are one of the biggest consumers of Japanese fashion, and that has injected a lot of money back into the fashion industry [in Japan], that’s great for the economy.”

Purchase Ametora on amazon.com or bookdepository.com. See more of W David Marx's work on his website.

0 User Comments