In ‘Getting Under the Skin of China's Cosmetic Surgery Boom,’ our August 2019 cover story, we take a deep dive into traditional China’s beauty industry.

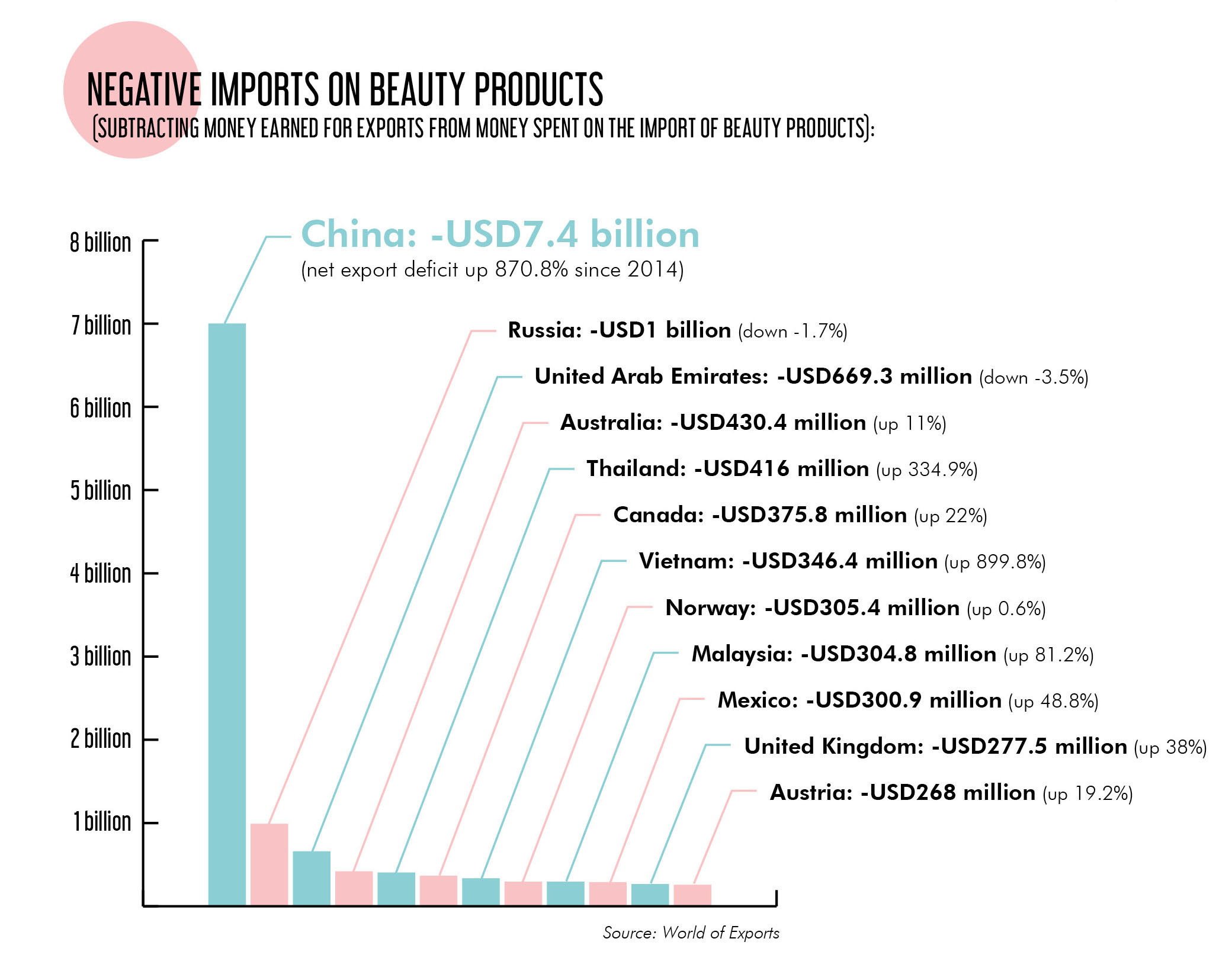

The numbers don’t lie; the beauty industry in China is rising fast. As demand for skincare products, make-up and surgical procedures grow, so are local entrepreneurs and corporations striving to nab a chunk of the pie.

Earlier this year, Japanese media outlet Nikkei Asian Review made the statement that beauty has become the new buzzword in the tech world, and it is certainly hard to disagree with that assessment. While other industries, like the manufacturing, automobile and tech sectors, have been slowing, the Chinese beauty market is booming, with a multitude of factors feeding its growth.

On the one hand, disposable income has risen in China. On the other hand, social apps like WeChat and Meitu in China – as well as Instagram, Snapchat and others – have changed the way people perceive how they look, and how beauty companies market their products to the world.

While the industry is undoubtedly changing, it seems that these alterations are coming at a great time for firms like L’Oreal, the biggest beauty company in the world. L’Oreal came out in June to say that its business in China has never been better, with sales doubling over the past four years and China now accounting for 10% of the company’s global sales.

As such, it’s fair to say that being beautiful has never been more important in China. But what exactly is driving this beauty industry boom?

‘Your Face is Your Rice Bowl’

“Consider the following Chinese proverb: ‘Your face is your rice bowl (脸蛋就是饭碗).’ It shows how important being beautiful is and how deep the roots of this attitude go,” London and Shanghai-based dental surgeon and aesthetic practitioner Souphiyeh Samizadeh reflects. She has been living between China and the UK for almost four years, acting as a visiting associate professor, while taking stock of the Chinese plastic surgery market and contributing to studies on modern beauty ideals.

The idea of beauty having a direct impact on one’s life, and the chances that a person has in life, is not new. Plenty of research into the existence of appearance-based bias in job markets around the world have found that the attractiveness of applicants has an outstanding effect on their success in getting a job.

As competition in China’s jobs market only seems to be getting more intense, it seems natural for recent graduates to fork out money for cosmetic surgeries – such as double eyelid surgery and botox – to improve their chances of making a good first impression on their resumes and in interviews (Note: Resumes in China often feature a job candidate’s photo).

“Plastic surgery means that those of us who are hardworking and studious don’t lose out in life just because we didn’t win the pretty lottery at birth”

This is what we call an unfortunate truth – a dirty secret that we, as participants in a so-called equal opportunity society, would like to ignore. In China, it is, as Shenzhen-based YouTuber and tech maven Naomi Wu points out, just one more aspect of society that is resoundingly unfair.

“Of course, anyone can choose to take the high road and opt out, but no one really cares in China if you are ‘natural.’ They’ll simply not get the benefits. Of course, it’s ‘not fair’ but neither is a rural hukou, the gaokao having such a definitive effect on your career trajectory or a million other things – China is not a fair place.

READ MORE: Naomi 'SexyCyborg' Wu on Internet Fame, Tech in Shenzhen

“Plastic surgery means that those of us who are hardworking and studious don’t lose out in life just because we didn’t win the pretty lottery at birth. While modern beauty standards are horrible, at the end of the day, brains can buy you beauty but beauty can never buy you brains.”

Wu herself has surgically enhanced breasts. “I wanted to look cartoonishly feminine even if that appearance was a bit at odds with my chosen profession,” she tells us. Wu made her living as a computer programmer before she began to create content for YouTube.

Since beginning her channel she has gained a huge following, with her highest-watched video sitting at the 35 million view mark. Her content largely revolves around gadgets and maker culture – not exactly the most popular topics in the world, yet she currently boasts over 900,000 subscribers. She has become, for some, a poster girl for the dynamic tech scene in Shenzhen and China as a whole, and at least some of that success can be attributed to her appearance.

Design by Ivy Zhang/That’s

As Wu points out, beauty has an undeniable effect on how we are perceived. In certain ways, it can predetermine how people treat us, how happy we feel, how successful we are. Essentially, it can determine what opportunities we get and where we can go in life. While people in China certainly have more disposable income than in years gone by, that does not translate to social mobility, as the divide between the richest people in the country and those closer to the bottom remains very large.

Modern innovations such as machine learning and artificial intelligence promise a world in which human prejudice is replaced by genuine computerized objectivity. While these machines have already been integrated for many uses in Chinese society today, we’re still a long way from these technologies reaching their full potential.

“I think most young Chinese people these days get plastic surgery for fairly practical, evidence-based reasons. More attractive people have better life outcomes in every society”

In a country like China, the brutally competitive job landscape has forced people to get creative in their search to gain a foothold in the job market. Parents are even putting their children’s genes to the test. In an article published by MIT Technology Review earlier this year, the publication explored talent testing in Shenzhen, a questionable means of prodding at the DNA of young children to discover their innate talents. While not necessarily related to beauty, this idea of gaining an early lead in the highly competitive education and jobs landscape is clearly driving people to extreme lengths.

“I think most young Chinese people these days get plastic surgery for fairly practical, evidence-based reasons. More attractive people have better life outcomes in every society, they earn more, are considered more trustworthy, more intelligent, receive more favorable rulings in court cases,” Wu reiterates, adding “It’s such an incredibly powerful unconscious bias that everyone thinks that they, personally, are immune to, but the numbers say otherwise.”

This unconscious bias not only applies to the job market, it seems. According to a recent study by social scientists at China Agricultural University, students in migrant schools are also subject to appearance bias when manually graded by teachers, with appearance accounting for a mark-up in language scores like English and Chinese, as well as maths. Just like the jobs market, the schooling system in China is immensely competitive.

Design by Ivy Zhang/That’s

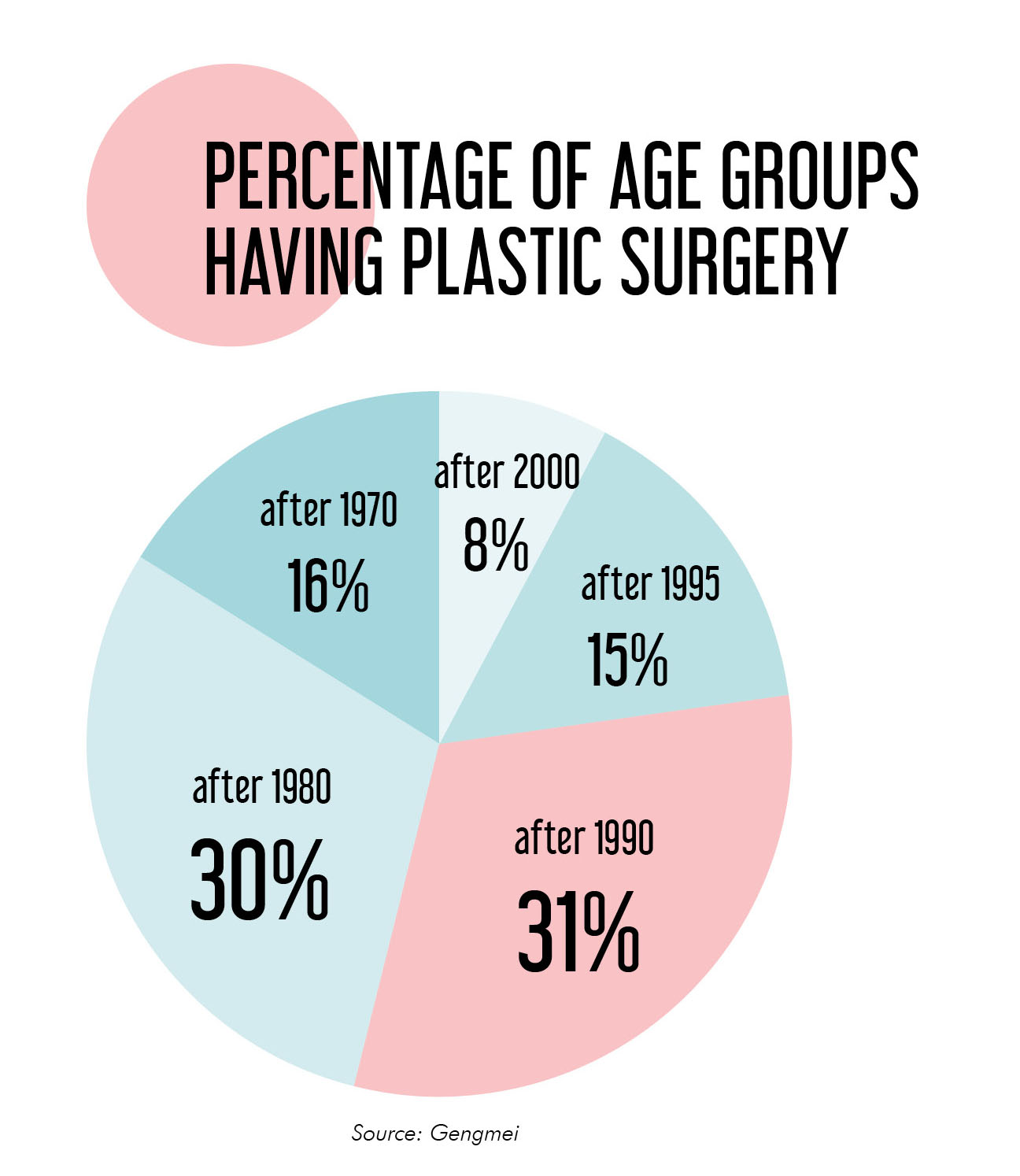

It’s hardly a surprise then, that the age at which people are having plastic surgery is getting younger. According to figures collected by Chinese company Gengmei, 54% of those who had cosmetic procedures in 2018 were under the age of 28, while people born after 2000, i.e. people of the age of 18 or under, accounted for 8% of those who had undergone cosmetic surgery. While that number pales alongside different age groups that took part in the survey, 8% of the 22 million people who did have cosmetic surgery in 2018 comes to around 1.75 million people under the age of 19, an enormous figure.

For many, this trend is frightening. While those of us who were not raised on the internet were told that beauty is only skin deep, increasingly younger generations are bombarded with Photoshopped, filtered pictures of physically enhanced models, actors and superstars. The age of social media is seemingly ensuring that a new phase of beauty has arrived.

In June of this year, Alipay announced that they would introduce beautifying filters for their facial recognition payment systems, after a survey undertaken by Sina Technology found that users were unhappy with the quality of the payment systems’ images.

READ MORE: Alipay is Adding Beauty Filters for Face-Scan Payments

The move feels significant. On the one hand, Alipay is pacifying customers who are clearly not satisfied with how they look while paying for goods. On the other hand, this move is another clear sign that beautifying filters are increasingly pervasive within modern Chinese society and are changing the way we interact with the world and the way we perceive ourselves.

Snapchat Dysmorphia

This latter point has been the cause of much concern. There has even been a term coined for this new form of body dysmorphia, ‘Snapchat dysmorphia,’ so-called because of the beautifying filters available for users of popular social app, Snapchat. The term was originally coined in 2018 by British cosmetic doctor, Tijion Esho, as a response to the rising trend of young patients using pictures of themselves that had been adjusted using photo filters to communicate the cosmetic changes that they want to be made when consulting with cosmetic surgeons.

In China, selfie culture has blown up, in large part due to the Instagram-like app Meitu. This selfie boom has made an empire out of Meitu, with plans now in place by the company to expand into physical services. Meitu is now worth almost USD5 billion, according to Crunchbase, with the company leading the way in virtual makeup try on services. A significant example of where the company is heading is its MeituSpa, an AI-powered skin cleansing device that provides personalized skincare recommendations, a powerful product for beauty die-hards in this technological age.

The beauty industry as a whole is increasing rapidly in China. According to Euromonitor, China is the second largest beauty market in the world, and is only getting bigger. Some of China’s largest corporations, namely the BAT (Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent) triumvirate, are branching out to meet the growing demands, and opportunities, in this market, investing heavily in up-and-coming beauty companies, while also creating products like Alibaba’s Magic Mirror, an 8-inch mirror equipped with a smart speaker, which adjusts light settings to give users a perfect view of their faces no matter the environment. The AI-device also offers users beauty tips and connects users with Alibaba’s Tmall platform.

Design by Ivy Zhang/That’s

Elsewhere, Tencent-backed cosmetic surgery social media application SoYoung Technology raised over USD175 million in a Nasdaq IPO earlier this year. SoYoung connects users seeking aesthetic surgery advice and procedures with knowledgable doctors, and has been downloaded over 10 million times. The company accounted for over one-third of China’s cosmetic treatments booked online in 2018.

Platforms like Gengmei and SoYoung are normalizing the consumption of cosmetic surgery. The idea of being surgically enhanced is scary to consider for some folks, but we are living in a new age where our communication options are enhanced, our ability to satisfy the majority of our desires from the comfort of our couch is enhanced and our ability to heighten our perceived beauty online has been enhanced. It stands to reason that, if the option is there, why not enhance our own beauty.

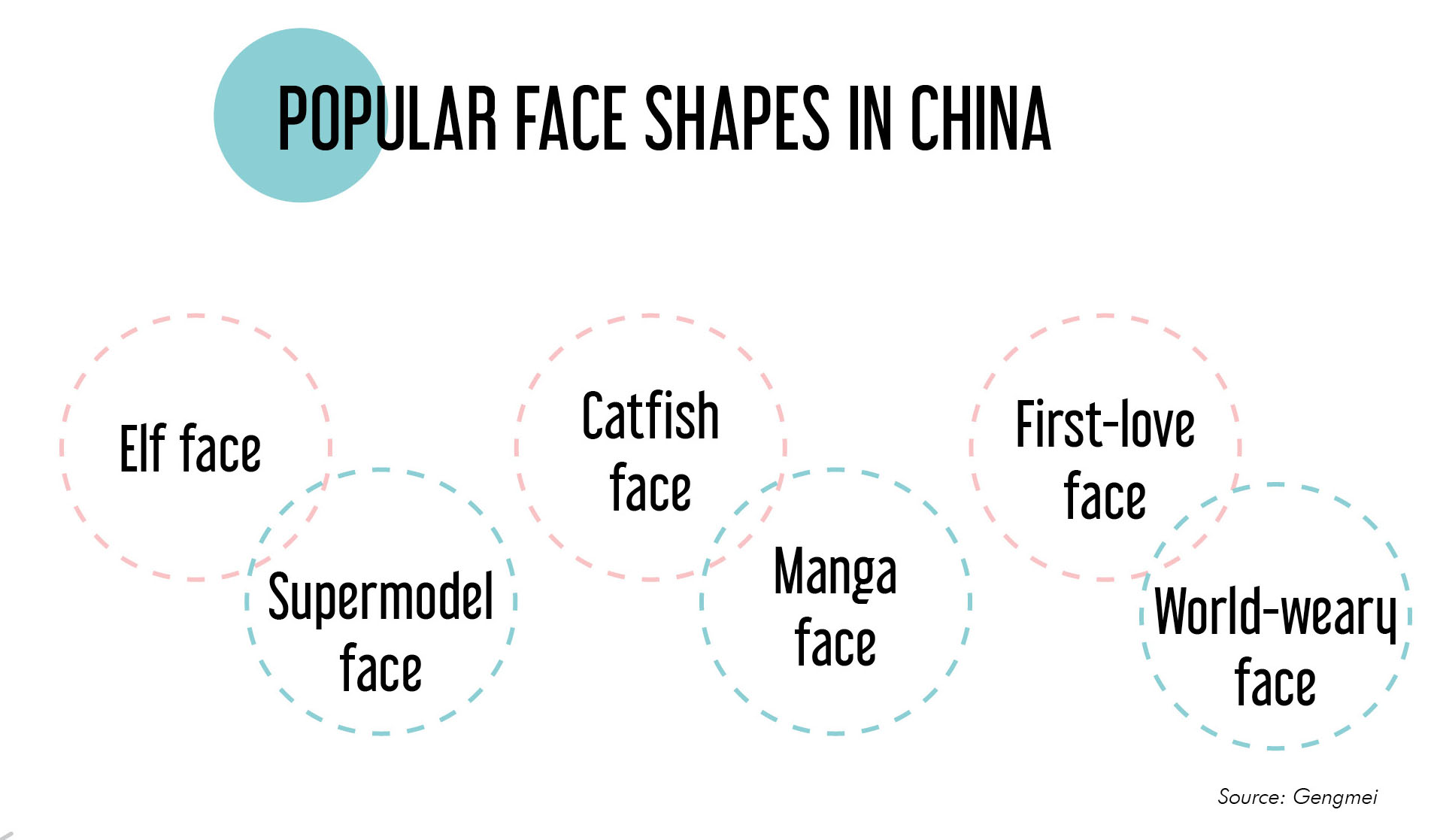

According to Gengmei’s report on the industry, such bizarrely named facial shapes as ‘elf face,’ ‘supermodel face,’ ‘catfish face,’ ‘manga face,’ ‘first-love face’ and ‘world-weary face’ have become popular options for young people seeking facial reconstruction.

For Zhou, a 21-year-old currently living and studying in Shanghai, she decided to have double eyelid surgery after seeing how well it worked for her friends. “I think it’s cost-effective to do double eyelid surgery. I’m satisfied with it. It’s a once-and-for-all deal,” she tells us.

Her father paid for her to have the surgery when she was 18, and since then has found that she feels more confident. While this particular surgery, which she had in a Shanghai hospital, worked out well, Zhou is unsure if she would have surgery in China in the future, saying that the country’s plastic surgery amenities are reputedly not as good as those in other countries, such as Japan.

Aesthetic practitioner Souphiyeh Samizadeh tells us, “In Europe, our clinics are still discrete and boutique like. In China you see very large cosmetic hospitals everywhere with marketing for cosmetic procedures all around you.”

Design by Ivy Zhang/That’s

In China, in order to garner more sales, cosmetic surgery apps like Gengmei offer discounts during the holidays and after graduation. The app also works in combination with Alipay’s microlending service Huabei, according to Sixth Tone, to help fund cosmetic procedures.

More personalized marketing strategies are also helping to sell beauty products. The age of wanghong (or Key Opinion Leaders) is allowing beauty companies to harness the specialized audiences and trust that fans have for KOLs to sell products and garner interest through social media outlets like Weibo, Xiaohongshu and Meitu.

And so, as this open attitude towards plastic surgery flourishes, and with the growth of platforms like Gengmei and SoYoung, as well as the continued growth in the number of cosmetic procedure facilities in the country, it seems like a matter of time before China is on a level with the likes of Japan and South Korea.

What Does the Future Hold?

The Asian market for plastic surgery is growing exponentially. Until recently, South Korea stood head and shoulders above the rest of the continent in terms of the country’s cosmetic services industry. It has been widely reported that the Asian nation has the highest rate of plastic surgery per capita in the world, with Business Insider estimating that somewhere between 33-50% of South Korean women aged 19-29, have had some form of cosmetic surgery.

Like all bubbles, however, that figure was bound to burst. In 2018, women in South Korea began to rebel against what they felt was a societally imposed idea of what beauty is. The ‘No Corset Movement’ picked up steam as notable livestreamers like Lina Bae began to support this movement away from cosmetics and beauty products. Bae’s move to align with the ‘No Corset Movement’ came with plenty of support, but also resulted in the YouTuber receiving death threats.

In some ways, what is happening now in China bears resemblance to the beauty industry landscape in South Korea. As Souphiyeh Samzideh tells us “In Asia, the majority of cosmetic patients are from the younger generation, this has been the case for a very long time. The idea of getting eyelid surgery as a graduation present from one’s parents is not uncommon or unusual here.” Of the young women that we spoke to about their cosmetic surgery procedures, the vast majority of them had been 18 or 19 when they went under the knife.

And while the infrastructure for plastic surgery is certainly increasing, there has, thus far, been very little online, or offline, reaction to the country’s growing beauty consciousness. The most popular cosmetic procedures have been, and remain, double eyelid surgery, botox injections or surgery to change the shape of the jaw, as well as dermal fillers to alter the shape of the bridge of the nose. Comparatively, popular procedures in the West generally aim to reduce the signs of ageing.

As Naomi Wu tells us “I think certain types of plastic surgery will fall in and out of favor. In the West, obviously, augmented breasts are vulgar and unfashionable in many circles, while fat grafting and black market filler injections are ‘in.’ Likewise, there is nothing in current plastic surgery fashion so deeply rooted in Chinese culture that it won’t fall out of favor eventually.”

The future for just about anything is uncertain, but, with all things being equal, you can likely rest assured that the market for beauty products, cosmetics and plastic surgery will keep on growing as beauty consciousness continues to change.

Additional reporting by Jack Douglas and Yihan Chen.

[Cover image via Hellorf. Design by Ivy Zhang/That’s]

For more on plastic surgery in China, click here.

0 User Comments