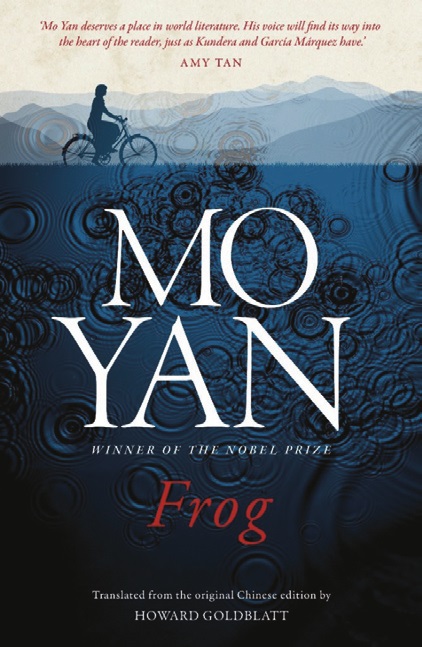

What to make of Mo Yan? Originally written in 2009, this English-language version has been much awaited by Anglophones eager to see what the fuss is all about. This is the most recent novel by the winner of the 2012 Nobel Prize in Literature after all, and the prolific Howard Goldblatt is the most lauded of the Chinese-to-English translators.

We haven’t read the earlier books, so can’t pronounce on Mo’s body of work as a whole, but this is a disappointment. Frog covers well-trodden territory with a surreal veneer that reduces our engagement with the characters, and adds a misbegotten final flourish.

As he has done previously, Mo sets the novel in his own childhood home of Gaomi County in Shandong Province. Born in 1955, he lived through the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution, and he has come at these subjects either obliquely or directly in his work.

The most important character, the narrator’s aunt (who in the novel is known as Gugu – father’s sister), is apparently also based on Mo’s own aunt; he has said he asked her not to read the book on the grounds that it would make her angry.

Gugu is a gynecologist, and a woman of fierce intelligence and courage, saving lives by replacing primitive childbearing methods with a modern medical approach. When her fighter pilot fiancé defects to Taiwan, her reputation is ruined and the Cultural Revolution goes hard for her.

Yet she still remains admired until the One-Child Policy begins to be implemented and her role becomes a rather different one. The drive of the novel for its first two thirds or so is her passage from heroism to fanaticism.

In a rare interview, Mo told Der Spiegel that “China has gone through such tremendous change over the past decades that most of us consider ourselves victims. Few people ask themselves, though: ‘Have I also hurt others?’ Frog deals with this question, with this possibility.”

It’s an admirable ambition. Yet that kind of probing is obscured by the growing absurdity of the plot in the later stages of the book, as Mo throws the stylistic kitchen sink at his themes.

The framing device is letters from narrator Tadpole to a Japanese professor friend, written from the vantage point of old age. It adds nothing to the book, and seems to be there to liberate Mo from a conventional narrative following Tadpole from the hard days of mid-century to today’s modern China.

It’s in these later present-day sections that things go wrong, with Tadpole and wife Little Lion stumbling on an illegal operation that comes to include a horribly scarred surrogate mother, a Don Quixote-themed restaurant and some pretty terrible behavior.

We are so far from reality here, and movement is so bogged down in metaphor and subsequent explanation of metaphor (the character ‘wa’, the Chinese name of this novel, can mean both ‘frog’ and ‘baby’ – you’d better believe that Mo grinds hard at this linguistic quirk), that we found our patience tried rather than our empathy won.

Mo Yan is clearly an excellent writer. At its best, Frog is engrossing, and its village of people become vivid through accumulation of detail and a precise grotesquerie (Mo has described his work as “peasant writing”). Late in the book there is a wonderful depiction of Tadpole chasing a thief, only to be turned on by the whole town and chased himself.

“What I don’t understand, Sensei, is why people have to be so horrible.” Here, the plaint is moving and earned. Early in the book, young Tadpole describes what it was like to eat coal, and in general the writing in early sections is nicely balanced between sharp accuracy and light satire.

And yet, and yet. Writing in the London Review of Books, Nikil Saval noted that “a boundless disregard of tone is indeed Mo Yan’s signature.” It’s a point well made, and the tendency of characters to move between earthy quips and grand declamation is a problem from the start.

Gugu’s highly symbolic form of madness in her later days is more literary device than neurosis, and the very end of the book goes badly wrong, with Tadpole deciding to write the last section of the story (remember, these are his letters) in the form of a play.

This form does have the benefit of zipping along, and illuminating the themes of selfishness and corruption, and the neverending sway of superstition; but it’s too much, too late.

But who are we to argue with the Swedish Academy? Readers should try Frog for themselves, since it’s been a divisive book from the start. We’ll be trying Mo Yan’s earlier books to find out what all the fuss is about.

// Frog by Mo Yan (Penguin) is available on Amazon.

0 User Comments