Throwback Thursday is when we trawl through the That's archives for a work of dazzling genius written at some point in our past. We then republish it. On a Thursday.

By Karoline Kan

It is approaching 1am on December 2, 2013. Deep in the remote Liangshan Yi Autonomous Prefecture, in the southernmost extremity of Sichuan Province, technicians in white lab coats and uniformed military engineers shuttle hurriedly across a large, open concourse. In the near distance, the Xichang Satellite Launch Center – China’s equivalent to NASA’s famed Kennedy Space Center – stands primed and ready, its towering No.2 launch tower spotlighted against the surrounding mountains. Two rows of emergency service vehicles, their lights piercing the winter mist, line the nearby verge.

Inside the adjacent mission control center, Commander Yan Liqing surveys the scene before him. For many in Yan’s team, this moment marks the culmination of over a decade of meticulous preparation. He clears his throat and turns to address the assembled crowd: “One minute until ignition!”

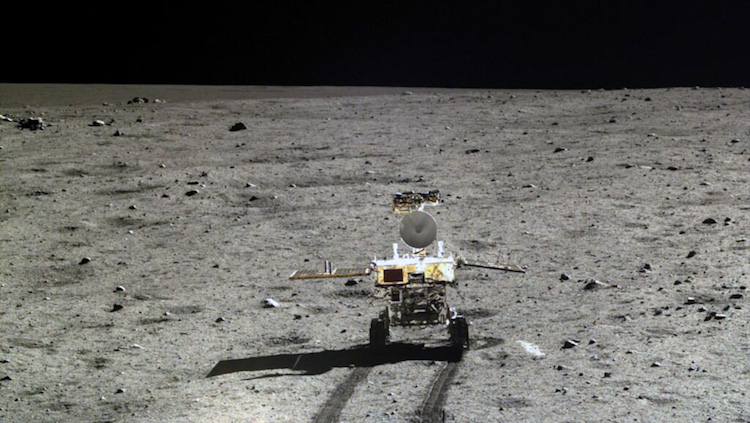

Throughout the vast complex, workers – among them, many of China’s leading scientific minds – turn their attention to the launch tower, to which the 3.7 ton satellite Chang’e 3 and its accompanying 120kg lunar rover, Yutu, are attached.

“Three… two… one… blast-off!” At exactly 1.30am, Commander Yan pushes down on the control panel’s red button, sending Chang’e 3 upwards above a column of intense heat and light. The thunderous sound echoes throughout the valley, waking villagers tens of miles away.

The launch, broadcast live on national television, marked a key event in the second phase of China’s Lunar Exploration Program (CLEP). Chang’e 3 took 21 months to design and a further 46 to construct. Its subsequent soft landing on the moon 12 days later announced China’s arrival as a genuine space power, placing the country alongside Russia and the US as one of only three nations to have achieved the feat and the first to do so in almost four decades.

China National Space Administration staff who worked on Chang'e-3 congratulated each other on the world's first successful lunar landing in 37 years.

“Now Yutu has made its touchdown on the moon surface,” announced state-run Xinhua news agency, “the whole world again marvels at China’s remarkable space capabilities.”

China’s ambitious lunar program, first initiated in 2003 by the China National Space Administration (CNSA), consists of three distinct operational phases – Orbital Mission, Soft Landing and Sample Return. The next and final phase, Sample Return, is expected to commence in 2017 with the launch of Chang’e 5, which scientists hope will lead to a manned lunar mission between 2025 and 2030.

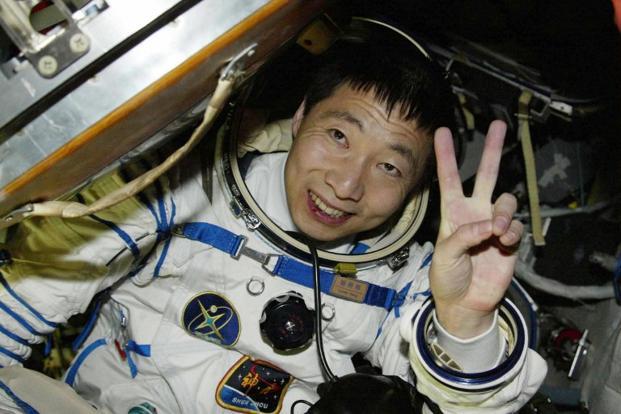

From the country’s first nameless R-2 rocket launching in 1960, to the success of its recent Shenzhou high-powered rocket program, responsible for its first manned space flight (Shenzhou 5, in which Yang Liwei became the first Chinese national to orbit the earth in 2003), China has positioned itself among the world’s leaders in space exploration in little over 50 years.

Its standing in the field was further enhanced in September 2014, when over 400 astronauts from 35 nations gathered in Beijing for the 27th Planetary Congress of the Association of the Space Explorers (ASE). The event, for years considered to be something of a low-key industry forum, was lit up by China’s decision to release details of its furthest-reaching plan to date: the launch of a provisional space station laboratory, Tiangong 2, and a docking spacecraft, Shenzhou 11, in 2016 – followed by the construction of its own permanent manned space station in 2022.

China's Chang'e 5-T1 experimental spacecraft returned spectacular images to control center in October 2014.

The announcement, however, led to concerns about China’s long term ambitions – the project would likely see the country enter into direct competition with the US, who, alongside Russia, maintain and operate the International Space Station (ISS). Deputy Director of China Manned Space Engineering Office, Yang Liwei (who was the first astronaut China sent into orbit), has since moved to rebuff notions of a direct contest with the Americans, stressing that, “space remains a shared resource for all human beings.”

Even so, under the auspices of the government’s ongoing campaign of “national rejuvenation,” China’s space program has quickly gained an air of patriotic fervor – with the advent of a permanent space station seen as a mark of national pride.

Wang Fan, a postgraduate student at Beijing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics (BUAA), the so-called ‘cradle of China’s space program,’ vividly recalls the excitement generated by China’s first man in space in 2003, the aforementioned Yang Liwei.

“I watched him re-enter the earth’s orbit live on TV with my family. For weeks, it was all anyone wanted to talk about. At school we studied it. We even answered exam questions on it. Math, physics, chemistry, politics, Chinese – everything was about China’s space program and our potential role in it.”

China's first man in space, Yang Liwei.

More than ten years on and Wang is now hoping to follow other top students from his university by securing a well paid position within China’s booming aeronautics industry. “It has been my goal to work in the space program since watching the broadcast in 2003,” he enthuses.

Wang’s aspiration aligns with the country’s own official Five Year Plan. In it, China’s leaders emphasize the economic benefits – particularly in relation to technological innovation – made possible by the country’s ongoing space program: “The position and role of space exploration is becoming increasingly significant and its influence on human civilization and social progress is increasing,” says the report. “Space activities will therefore play an important role in China’s ongoing economic and social development.”

READ MORE: China Plans to Send Tour Groups to Space by 2025

Ma Ruixing, director of state-owned China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation (CASC), the main contractor for the Chinese space program, is clearer still.

“Aerospace science and technology is known in the industry as ‘gold mine technology’ – for every 1 yuan invested, between 7 and 12 yuan is returned,” he explained in an interview with People’s Daily in 2014. “So far, China’s investment in this field is estimated to have created a chain of industry that is worth in the region of 120 billion yuan.”

Not everyone is quite so enthusiastic. In a country where basic sanitation remains rare in rural areas, and more than 82 million people live on less than 6 yuan per day, the use of up to 2 billion yuan of public funds to help finance prestige projects – with little clear social value – has proved controversial.

"If you spend 2 billion yuan, you can build three new subways in Beijing. But can you claim to be a rich and powerful country by building subways?"

Professor at the school of astronautics at BUAA, Dr. Li Weipeng, says he understands why some might question space expenditure. “In the US space program, the standard input-output ratio must be 1:6, due in part to pressure from tax payers. In China, most aerospace projects are political, and have no such budgetary constraints.

“China’s lunar ambition is derived from its sense of inferiority,” Li continues. “Becoming a rich and powerful nation is foremost on the Party’s agenda. If you spend 2 billion yuan, you can build three new subways in Beijing. But can you claim to be a rich and powerful country by building subways?”

Although China is now confidently among the world’s leading spacefaring nations, it remains some distance from taking a more dominant role, Li insists.

“I think fear of China as a threat is unwarranted. Although the whole country is very excited and proud of what we’ve achieved, key facts are always ignored. Remember, China was late into the game – we are still decades behind the United States.”

The gap is decreasing, however. Whereas the US space agency is laboring under increased budgetary constraints and dwindling public interest, the Chinese space program is enjoying unprecedented levels of support.

China successfully launched Shenzhou-11 from the Gobi Desert in October 2016.

At BUAA, which falls under the supervision of China’s Ministry of Industry and Information Technology – rather than the Chinese Education Bureau – due to its special position within the country’s space program, China’s future aerospace engineers routinely work late into the night.

“We are different from most students at other universities. In engineering science, you either give 110 percent or you move aside,” says Wang.

According to Dr. Li Weipeng, there is an unwritten rule in the industry that failure – no matter small – cannot be tolerated, putting students like Wang under immense pressure. “We call it the ‘zero policy,’” Li explains. “No matter how good you are, if you make a single mistake, your career is doomed.”

In 2014, less than two months after touching down on the moon’s surface, the Yutu rover reported problems due to “complicated lunar conditions.” Chinese authorities downplayed the incident, but within the space program, heads began to roll.

“A friend of mine who is a member of the project team spent two weeks straight in the office, without once leaving, or changing clothes, in a desperate attempt to figure out the problem,” reveals Li. “The space program is of paramount importance to the country – and there is fierce determination to succeed.”

China’s Jade Rabbit (Yutu) moon rover experienced a 'mechanical control abnormality,' state media said, in what was a setback for a landmark mission in the country’s ambitious space program. The expedition was foiled by a rock.

Back at BUAA, Wang Fan is preparing to spend his weekend working in the Spacecraft and Missile Technology laboratory, along with 15 other students.

“The theory is always far ahead of the practice. I don’t know exactly which project this experiment will be used for, although if I even did know, I wouldn’t be able to reveal it to you,” says Wang, who, like all students at BUAA, has signed a confidently agreement. “You know, the first lesson that students here learn is the importance of national security.”

On the other side of campus, postgraduate students at the School of Aerospace Engineering are listening intently to lecture being given by the Secretary General of Chinese Society of Astronautics, Li Huifeng.

"Aerospace science and technology is known in the industry as ‘gold mine technology’ – for every 1 yuan invested, between 7 to 12 yuan is returned."

“Your personal career route should be closely attached to the nation’s demands,” she tells them. “When I graduated, nobody wanted to work in scientific research institutes, due to the low income. But after the Chinese embassy in Belgrade was bombed by the US in 1999, everything changed. Your work is highly valued.”

This sense of value is likely to propel students like Wang into the heart of China’s space program, where they can expect to receive vast rewards, should they be able to cope with the pressure. But beyond the sense of national purpose, China’s mission claims a more universal goal. “We must push forward in our exploration of planets, asteroids and the sun,” says the government’s Five Year Plan.

Such ambitious targets do not only reflect the infrastructure and financial backing that is now in place for the space program, but also a confidence about the country’s position here on earth. Exploration of our galaxy has always been a luxury for those nations with money to play with and a point to prove. China now has both.

But to view its ascent in the context of a Space Race propaganda battle ignores the changes aeronautics may offer. The prospect of mining moons and planets for minerals and resources, for instance, demonstrates potential commercial incentives that were largely absent during the Cold War, when the US first propelled itself to the forefront of the space industry.

As ever, the possibilities remain unknown. But one thing is clear: China seems intent on being the one to find out.

This article first appeared in the November 2014 issue of That's Shanghai, That's Beijing and That's PRD. To see more Throwback Thursday posts, click here.

0 User Comments