This feature is part one of our June 2019 cover story. Check out the full story right here.

“The teachers hit us. Hard.”

As he retells his story, Xu Xuan makes it clear that becoming a Chinese opera actor is no easy feat.

“At the vocational school, we had physical training in the morning, involving martial arts, with kicking, jumps and acrobatics. We woke up at around 7am, had a quick breakfast and then immediately went down to training, until around 11.30am. Then, in the afternoon, we had to train for the operas themselves – the spoken and singing parts.”

Xu had just come out of elementary school when he started his long and grueling apprenticeship at the vocational school of the Jilin Municipal Opera Company. It was his mother who first suggested he pursue a career in theater.

“Your life will be very different from that of any other child,” she told him. “You won’t be spending time at a normal school and playing around with other children. But it will be worth it.”

“My mother knew all the revolutionary operas from the Cultural Revolution by heart,” Xu says. “They would always be playing in our house as I grew up.”

A young Xu Xuan during a representation with the Jilin Municipal Opera Company, 1997. Images courtesy of Xu Xuan

As Xu tells me, a career as an opera actor was considered a viable and stable path for a young child passionate about music, dancing and fighting. It was a typical tiefanwan job, the ‘iron rice bowl’ employment that assured a steady income and subsidies to those who could get it. For this reason, he and his peers were tireless in pursuing their training.

“It could be very frustrating. It’s not that you tried a jump and could immediately master it. The repetition could get really boring. After all, martial arts in Chinese are called gong fu, and gong fu in Mandarin also means the time and effort you invest in an activity.”

“But we were young boys who dreamed [of becoming] good actors one day. We were motivated. We would think ‘I like this story, I want to do this,’ so we would ask the teachers to start from there, to teach us that piece we liked. Our minds were in the right place.”

This was because, as a symbol of China itself, Chinese opera was, in his parents’ minds, a prestigious field of work and an industry the state would always support.

They had reasons to believe this: China has always been ready to defend this tradition and to teach others to treat it carefully.

In 1998, American director Chen Shi- Zheng was in Shanghai preparing his ambitious staging of Peony Pavilion (Mudan Ting), the Ming dynasty masterpiece by Tang Xianzu. Commissioned by New York’s Lincoln Center for the play’s 400th anniversary, this 19-hour, three-day-long play was set to be the main attraction of the center’s summer season.

It involved bringing one of the most famous pieces of Chinese theater to the US in its integral form, enacting on stage the entirety of Tang Xianzu’s 55-scene text through a philological work that had never been attempted before in China. For the first time since the Ming dynasty period, the audience would have been able to follow the entire arc of heroine Du Liniang as she consumes her first love with scholar Liu Mengmei in a dream, dies and is resurrected by her lover (the real one, this time) to finally triumph at the imperial civil service examination.

To complete the project, Chen collaborated with the Shanghai Kunqu Company (also known as Shang Kun), and set out on an eight-month-long design and rehearsal run with the troupe in the PRC. At the end of this period, the long-awaited production was almost ready for the stage. Almost.

During a dress rehearsal held behind closed doors in Shanghai, in the presence of a number of scholars and the press, an official from the local tourism bureau thought what he saw was a misrepresentation of China's operatic tradition. Chen's Peony Pavilion was deemed “pornographic, feudal and superstitious.” Soon after, the production was forced to a sudden halt and the entire troupe was prevented from leaving Shanghai for the US, with most of the props confiscated at the airport.

Xu Xuan dressed for one of his roles. Image courtesy of Xu Xuan

Chen underestimated the importance this form of dramatic tradition held in the eyes of Chinese authorities, and in Shanghai, given its proximity to the birthplace of kunqu opera (the particular style that Peony Pavilion is performed in) – the city of Suzhou.

But the wake-up call was not enough to stop the foreign producers. In 1999, the director set up a rerun with American-Chinese performers, again at the Lincoln Center. Though this time, it was not the only sensational production being staged. During the same year, two other headline-grabbing productions of Peony Pavilion were touring around China and the US, making 1999 known as the ‘Year of Peonies’ in art circles.

One was done by Peter Sellars, the American director famous for his contemporary, iconoclastic renditions of operas and plays. It featured music by Tan Dun, though very little of the kunqu form’s common characteristics. The other, which only toured in China, was staged by none other than Shang Kun, the ensemble Chen Shi-Zheng originally collaborated with, this time strictly adhering to the traditional staging form.

“I think [China] was reacting in particular to Chen Shi-Zheng’s production,” Catherine Swatek, former professor of Chinese language and pre-modern literature at the University of British Columbia and author of Peony Pavilion Onstage, tells me. “I think what bothered authorities was the scene conception: He wanted to make it something that was not kunqu, to take it back to its roots in folk theater.”

The Shang Kun show was thus ultimately a statement, an attempt at defending a canon with which they identified. “He violated kunqu's aesthetic. [...] He vulgarized it.” That aesthetic, though, hadn't always been there.

“Operas were written out of the tradition of the southern folk theater,” Swatek adds. “It was then taken over by highly-literate scholar officials, who embraced it [...] and turned it into a vehicle for their own aesthetic tastes, personal feelings and even political stances.”

Indeed, Chinese opera is a relatively young form of entertainment, codified between the 15th and 19th centuries. When Tang Xianzu set out to write his masterpiece, it was a form of creative writing infused with taboo themes like sexual desire and the death-defying power of passion, as experienced by the heroine of Peony Pavilion.

Later the Qing dynasty, which reined from 1644 to 1911, was responsible for the sudden popularization and institutionalization of Chinese drama, which became one of the favored forms of entertainment by the court and, for the first time, publicly available.

During this period, the majority of China’s stage traditions emerged and spread, forming a cultural image that is now often defined as ‘Chinese opera.’

China National Peking Opera Company (CNPOC) actors Liu Dake and Zhang Jiachun in Turandot. Image courtesy of the performers and of the CNPOC

That being said, ‘Chinese opera’ is actually a contested umbrella term used in Western countries.

The term ‘opera’ projects onto Chinese drama the form and tradition of European opera, which mainly centers around singing, as opposed to its Chinese counterpart, which fuses singing, spoken word, acting, hand gestures and even martial arts and dance.

It also oversimplifies the complex ensemble of different genres that make up Chinese drama. A better term, used in China today to refer to the country’s theatrical traditions in general, is xiqu, meaning ‘stage drama.’ Recorded xiqu forms total at around 200, ranging from the powerful arrangements of Peking opera (jingju) to the ephemeral beauty of the delicate singing and gestures of kunqu, to which Peony Pavilion belongs.

But when, and how, were these different forms combined together to make up the general concept of xiqu?

Most scholars point to an indissoluble bond between the institutionalization of xiqu and the birth of China as a modern nation.

"Guoju represents one of the roots of our culture – we consider it as part of our identity as Chinese people."

At the start of China’s so-called ‘century of humiliation,’ with the country entering a semi-colonial status for the first time in its history, Chinese intellectuals undertook a large-scale redeeming and reforming endeavor that would culminate in the May 4th Movement.

This involved adapting some tokens of Western thought and technology, while rediscovering the roots of Chinese culture and adapting it so it could speak to a growing public. In the process, reformers identified xiqu as an art form embodying China, its culture and, because of its origins, also its people.

At this time, drama theorist Qi Lushan put Chinese opera at the center of a new cultural strategy. At the start of the 20th century, he contributed to coining and popularizing the concept of guoju (national drama). He then selected Peking Opera (jingju) as the xiqu tradition best suited for the role of a centralized national drama, making guoju and jingju synonymous. With the eventual popularization of the guoju concept, a national tradition was solidified. Defining it as such, the newborn Chinese nation was now able, and willing, to use xiqu as a diplomatic and soft-power tool.

The world did not have to wait long to see Chinese drama deployed for political purposes. In 1930, the venerated performer Mei Lanfang, famous for his performances where he impersonated a female character (called dan), embarked on a highly publicized tour in North America.

The goal was to pursue the support of the US, which was actively enforcing the Chinese Exclusion Act, amidst facing the threats of a growing Communist power and an impending Japanese invasion.

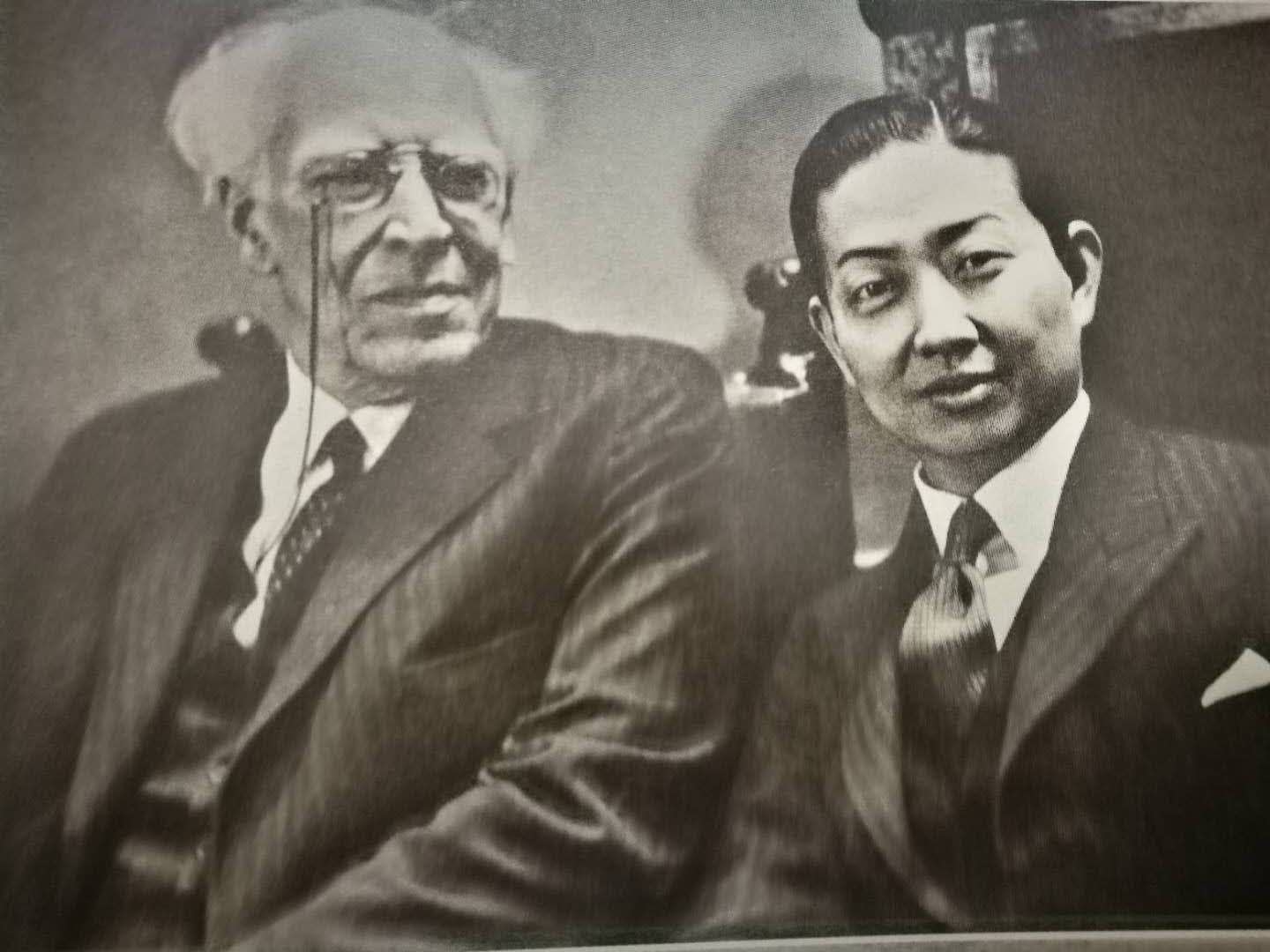

Mei Lanfang poses with Charlie Chaplin during his 1930 tour in North America. Image courtesy of Yu Liwei and the Mei Lanfang Memorial Hall.

Mei Lanfang with Kostantin Stanislavski during his 1935 tour in the USSR. Image courtesy of Yu Liwei and the Mei Lanfang Memorial Hall.

Performing masterfully, and repeatedly speaking about peace in public appearances, Mei Lanfang left a mark on Western cultural circles, becoming a modern icon of national culture. As China was about to enter one of the darkest periods of its history, and dan roles were about to disappear as xiqu started admitting female actors, the 'national drama' would not have a similar period of foreign exposure for decades. Its importance, though, did not fade.

“Opera is still used for soft power,” Josh Stenberg, lecturer in Chinese studies at the University of Sydney, tells me. “The Chinese government is spending enormous amounts of money to send Chinese opera troupes abroad. It's cultural diplomacy.” While completing his PhD at the University of Nanjing, Stenberg became the first foreigner ever to be employed at the Jiangsu Kun Opera Troupe, a position which allowed him to have a deep understanding of the role guoju plays in the eyes of Chinese authorities.

He explains: “The past few years brought about a new cultural nationalism that values tradition at large. There has been a large policy shift to support cultural products that can be associated with the ‘grand tradition.’”

"The Chinese government is spending enormous amounts of money to send Chinese opera troupes abroad. It's cultural diplomacy."

Talking with professionals from the industry is enough to realize how Chinese opera today retains its power to unify people in the name of that same tradition.

“Guoju represents one of the roots of our culture – we consider it as part of our identity as Chinese people,” says Liu Dake, one of the headliners of the National Peking Opera Company (CNPOC), China’s top-ranked government-backed opera troupe. Founded in 1955, it falls directly under the supervision of the Ministry of Culture and consists of three actors’ troupes and theaters.

Zhang Jiachun in Faust. Image courtesy of Zhang Jiachun and the CNPOC

As such, it is a fundamental institution for the promotion and protection of this cultural heritage, or as Liu puts it: “The mission of the CNPOC is […] to demonstrate, to guide and to represent.” That is, actors in the CNPOC, as much as any others from the officially recognized troupes, are not just supposed to perform, but to embody the art of guoju, and inspire future generations to keep it alive.

When asked what guoju actually stands for, Liu replies with five characters: “Chang, nian, zuo, da, fan.” That means “singing, acting, physical expression, martial arts and acrobatics” – all the talents needed to become a proficient actor. “Jingju actually represents all of these and all of the country’s hundreds of different traditions. That’s also why we consider it a pretty much perfect form,” he adds.

Liu thinks this is why it has not changed much since gaining its mark of officiality at the start of the 20th century. That’s also why, for an actor like him, working at the CNPOC is the ultimate goal. As the top xiqu institution in the country, it benefits from state subsidies and incarnates the excellence of the art. It means being recognized as one of the elite performers in China.

That was exactly what Xu Xuan and his classmates hoped for back in Jilin. Though reality would soon hit. After finishing at the vocational school, Xu went on to complete four years of training at the renowned Beijing Drama Academy.

It was there that he and many other students realized their dreams of becoming actors. But the benefits their parents told them about appeared less desirable than before. With globalization speeding up in the early 2000s, and the economy booming, the entertainment industry was transforming radically, with movies and TV becoming the go-to media of China’s fledgling middle class.

“The young boys our age who made movies became stars and could earn a lot of money. We started to ask ourselves why we were working our asses off training to earn a meager salary in a state company while they were making public appearances for 100,000 yuan,” Xu tells us.

“We considered ourselves more artistic, more talented and able to do more than the movie stars could. But parents around China understood that an investment in this career brought nothing. Students became less and less [interested] until the culture department decided to make the university and vocational schools free.”

Portraits of Xu Xuan in character, shot during his time at the Beijing Drama Academy. Images courtesy of Xu Xuan

Xu had graduated only a few years before, at the cost of tens of thousands of renminbi a year, when this was decided in 2009. Chinese opera was losing its grip on young audiences and a mediocre, albeit stable, job at a state company like the CNPOC did not look like much at a time when young people were accumulating huge fortunes as self-made entrepreneurs.

And Xu himself was not ready to settle for a job at a state company for life. “After my graduation, I could have entered the CNPOC easily, but I decided to leave. I could not bear to spend my life there. I was very courageous and young, and wanted to go abroad,” he says.

With a scholarship from the Italian Ministry of Culture, 21-year-old Xu landed in the Italian city of Pordenone, where he studied commedia dell’arte at the local experimental drama school. His time in Italy changed his views about Chinese opera and reinforced his belief that it had to evolve if it wanted to survive, and that Chinese performers would benefit from being exposed to different theatrical forms.

"We considered ourselves more artistic, more talented and able to do more than the movie stars could."

But changing an art form that audiences and performers alike consider to be perfect is easier said than done.

“We used to say that Chinese opera is already perfect,” says Xu, echoing Liu Dake's claim, “and this is the dominant thought in the industry. After the Cultural Revolution, many tried to add more elaborate set designs and real objects into the scenes, but old masters protested,” he adds.

The story of Chen Shi-Zheng’s Peony Pavilion can be taken as proof that the industry and authorities who are tasked with protecting this art form are averse to change. Still, it seems like the resistance to new forms and to the introduction of non-canonical components is not as strong as it was back in 1998.

In 2015, the CNPOC embarked on its very first ‘transcultural’ production, staging two Western dramas of worldwide fame, Faust and Turandot, using Peking opera costumes, acting and music. Liu Dake was the first to lobby for the project, which was born from a meeting he had in Europe with a German director who was participating in one of CNPOC’s workshops.

“I liked the idea of bridging cultures and adapting Western operas with Chinese theatrical forms,” he tells me. “I believe [Chinese opera] has to change if it wants to survive.”

In fact, the most recent innovations in staging productions come from the stated desire of Chinese authorities to make this art form a spearhead of China’s soft power expansion. As Liu explains, “Institutions like the CNPOC invest money in productions and educational activities that are targeted to draw in more audiences, often also abroad.”

In 2010, the Peking University Opera Academy was founded in Beijing, a first-of-its-kind institution that offers programs in both Chinese and Western opera styles, as well as researches and implements new forms in both traditions. In 2016, the State Council Information Office launched a new campaign, dubbed ‘Chinese culture walks out,’ tasked with devising ways to promote China’s heritage both inside and outside the country.

"I believe [Chinese opera] has to change if it wants to survive."

Abroad, Chinese authorities have been promoting Chinese opera mostly through the worldwide network of Confucius Institutes around the globe, or partnerships with scholarly institutions in foreign countries. Given the relatively niche status of Chinese drama overseas, there are only a few places where it is possible to access xiqu abroad.

“Foreign audiences don’t have very good access to the best of Chinese theater,” says Stenberg, from the University of Sydney, pointing to the nature of the performance as one of the reasons why it might be of low commercial value abroad. “[It] works best when the performance is in a sufficiently small space, as it allows you to be close enough to the performers to see their faces. You just can’t scale it up – if you do, it loses its uniqueness and becomes commercial theater.”

In fact, Chinese institutions have usually opted for traditional staging of Chinese dramas, or for workshops and exchange programs, to bring the art to different spectators, usually having to settle for relatively small audiences. This is what made Faust and Turandot quite unique, featuring new stories chosen to help a larger western public digest the foreign artform more comfortably.

They were CNPOC’s first attempt at what Stenberg calls “transnational theater,” though they are not by any means new. Outside of China, these ‘fusion’ operas have been some of the most impactful ways through which foreigners came to know Chinese theater and gave rise to innovations that found no space at home.

Zhang Jiachun and Liu Dake in Faust. Image courtesy of performers and the CNPOC

Peony Pavilion and its reinterpretations are of course an example. But the operas composed by Tan Dun, who was part of the first generation of Chinese composers who found success outside of China, were also groundbreaking for their musical scores, which combined the pipa (a traditional Chinese instrument) with Bach’s counterpoint.

And so, the question remains: Should China pursue this same approach when it comes to innovating? In a piece for Sixth Tone, Yang Yimin, professor at the Peking University Opera Academy, discussed the dilemma, pointing out that China has actually been doing this for a long time already. He defined a so-called ‘new opera,’ which “emerged in 1945 with The White-Haired Girl and combined ‘Western compositional structures with Chinese singing.’”

"I expected to see something that hit me, something exceptionally exciting [...] But instead it was just the same gestures, the same masks and costumes of traditional Peking opera."

In short, the Chinese opera tradition might not be as strict as it is thought to be. Stenberg has dedicated a long time investigating the innovation of xiqu in an attempt to go beyond what he called in one of his publications a “slippery idea of tradition.” He argued that “there can be no doubt of a drastic, unavoidable and constant change.”

One such case, he points out in one of his papers, was Shanghai opera at the start of the 20th century. Flying in the face of tradition, yueju, a local style of opera, was turned from male to entirely female performed for commercial gain at a time when women’s equality was the talk of the day.

That goes to say that the practices Liu or Xu might find constricting have really been the result of a succession of innovations, cautiously devised not to denature what was considered an important tradition. Some, in fact, think a rejuvenation of the forms of xiqu with respect for the art can be achieved, and should be the way to go.

Kenneth Pai is one of them. At 81 years old, Pai is a retired professor from UC-Santa Barbara and an author of fiction, plays and movie scripts. When it comes to xiqu, he embodies a true success story, since he set out to revitalize the tradition with his 2004 Young Lovers edition of, among all things, Peony Pavilion.

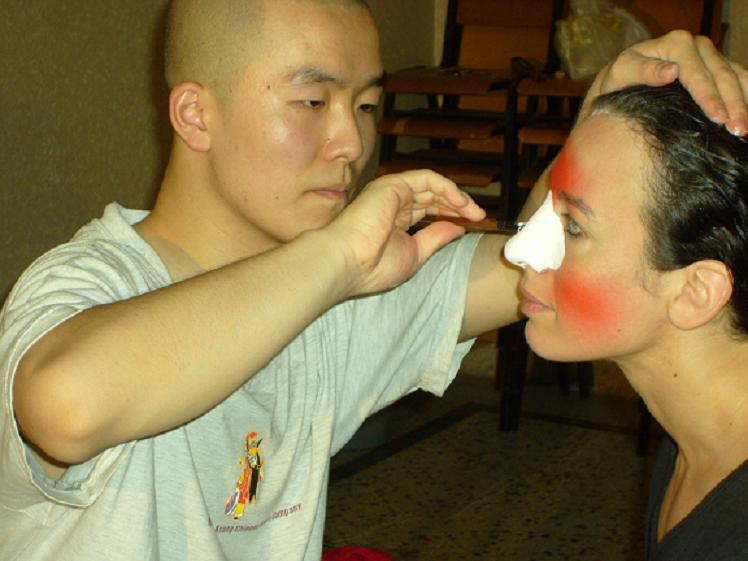

Xu Xuan applying makeup on an Italian actor during a Chinese opera workshop. Italy, 2007. Image courtesy of Xu Xuan

With incredible success in China – especially with the elusive young audiences – and rave reviews abroad, he seemed to have found the recipe to make xiqu palatable at home and overseas, while proposing yet another long-form rendition, in 29 acts.

“We successfully combined tradition with modernity, which explains why our production attracted a large crowd of young people, especially college students,” he tells me.

In opposition to what the performers seem to believe, he sees the problem of promotion and adaptation in a different light. “Peony Pavilion is Tang Xianzu’s greatest work – the peak of Ming drama. It is a most beautiful and romantic love story, comparable with Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet,” he says. “We kept the original production intact without making any compromises to cater to foreign audiences […] and with its 300 performances all around the country, there are obvious signs of renewed interest in [xiqu] among the young audiences.”

That is, if you know how to find the right way to stage it.

Faust and Turandot were quite well received in Italy, but were far from being a success. Xu, who saw Faust, felt let down by the final product: “I expected to see something that hit me, something exceptionally exciting, something that made me think ‘Oh, you can also do it this way.’ But instead it was just the same gestures, the same masks and costumes of traditional Peking opera.”

"These are the first steps towards innovation. We can fall, we can fail, but slowly we can study how to get better."

Both Chen and Sellars' productions of Peony Pavilion in 1999 also ended up receiving mixed reviews, both in China and abroad. Pai is on the same side: “As far as kunqu is concerned, I do not believe the arbitrary mixture of orthodox kunqu with Western music is the right development. Judging from the many failed productions of such ‘innovations,’ I have strong doubts about its future.”

Among all the voices in this ongoing debate, everybody agrees on at least one point: Chinese opera needs to change to survive. Though the process of finding the right way to bring it to younger and larger audiences is not straightforward, it clearly needs to consider the role opera plays in the hearts and minds of the people of China.

In Xu’s words: “These are the first steps towards innovation. We can fall, we can fail, but slowly we can study how to get better. I can see a new willingness in pursuing change, and that’s all that matters.”

[Cover image courtesy of Zhang Jiachun and the China National Peking Opera Company]

0 User Comments