Last summer, Zhao*, 30, a victim of domestic abuse, called the Maple Women’s Psychological Counseling Center for advice. She had suffered years of mistreatment, not only from her husband, but also her mother- and father-in-law. On one occasion, after Zhao sought refuge at her parent’s home, her husband tracked her down and, in a fit of rage, violently attacked Zhao and her family.

She had managed to flee her abusive husband with her son, but was afraid of what might happen next. What if he found her? What would happen to her – and her son?

Every day dozens of domestic abuse victims from around China seek help from Maple Center, either via its hotline or through face-to-face sessions. Located on the first floor of a residential apartment building in Xicheng, Beijing, the center assists callers by talking through available options, such as separation or couple’s counseling. It also conducts research on domestic violence and provides advocacy for victims.

The center advised Zhao as best they could. But with China’s anti-domestic violence law having come into effect on March 1, visitors and callers now have a concrete legal foundation – specific to domestic violence – in which to seek redress.

Founder of the Maple Center, Wang Xingjuan (pictured above), tells us during a visit: “The law is a good start because abused women can now seek [legal] justice. The law has a lot of bright spots.”

Indeed, anti-domestic violence advocates regard the specialized law as a victory for human rights. It offers legal acknowledgment of a deeply ingrained social problem that, in Chinese society, has traditionally been viewed as a ‘private’ issue.

Women would go to the police and the police would say: ‘It’s a family matter so it doesn’t concern us.’ But now the government has made it so that people have to care. It’s not a ‘family problem’ anymore, it’s a national problem

The law intends to combat domestic violence by focusing on prevention. It combines education, correction and punishment measures for a more proactive approach.

Notable provisions include: an increase in the scope of what can be considered domestic violence (family members and non-family members “living together” can all be prosecuted); the conduct covered (which now includes psychological as well as physical violence and restrictions on physical liberty); the duty or right to report; and the establishment of a written warning system. The law also makes it easier to apply for protection rulings and orders than in the past.

“Women would go to the police and the police would say: ‘It’s a family matter so it doesn’t concern us.’ But now the government has made it so that people have to care," Wang says. "It’s not a ‘family problem’ anymore; it’s a national problem.”

A volunteer at the Maple Center answering a call.

But how big a national problem is it? A United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) study, conducted in 2013, found that 39 percent of female respondents in China reported experiencing “physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence.”

The study also found that of those women who had experienced “physical partner violence,” 40 percent had been injured to the extent that they had to take leave from work or stay in bed. Estimates of lost productivity resulting from domestic violence in developing countries range from 1.2 to 1.4 per cent of GDP, according to the International Labour Organization.

Lawyer and anti-domestic violence advocate, Siodhbhra Parkin, spent four years researching domestic violence in China before moving from Beijing to the US, where she is now based at the Yale China Law Center.

Speaking with us over Skype, Parkin says: “Most people are quite happy with the law because it’s vague in the right ways and there are some relatively progressive provisions. For example, it allows for prosecution of domestic violence committed between partners who are unmarried but cohabitating. The law doesn’t mention gender, which is important because, potentially, LGBT individuals might get protection from this as well.

“One important element of the law is the protection order program,” Parkin continues. “If your partner is beating you, you can apply for what is essentially an injunction against them. [The law] also notified schools that it’s mandatory to report suspected acts of violence in homes of children in school.”

Other organizations singled out for mandatory reporting include medical establishments, residents’ and villagers’ committees, social work service organizations, and employees of the above. According to article 35 of the law, if the individuals responsible for reporting instances of domestic violence fail to do so, they will face punishment.

But the law has its shortcomings. In particular, it still fails to explicitly cover sexual violence, which discourages victims of sexual abuse from coming forward, and perpetuates the idea that people can act as they please in an intimate relationship.

Also, as Parkin notes: “A lot is still left to police discretion in terms of whether they choose to investigate and prosecute. We were also not thrilled with the police’s written warning system, which [may mean no more than] putting the case on a pile.

“But at least [the police] can now put it on the record, so if any future acts of violence take place, or divorce proceedings commence, there will be a record of [domestic violence] incidents, and the victim may have more power of getting something out of the situation.”

The law was over ten years in the making, aided by rights activists’ tireless campaigning. The drive was also buoyed by high-profile cases such as Li Yan, who, after months of abuse and a lack of help from authorities, beat her husband to death. Following a huge public outcry, the Supreme Court overturned Li Yan’s death sentence in 2014.

Another influential case was that of an American woman Kim Lee who made Chinese legal history in 2013 when she was granted a divorce on the grounds of domestic violence, as well as securing a three-month restraining order against her abuser, Crazy English founder Li Yang. Lee first brought attention to her case by uploading images of her injuries on Weibo and by publicizing her futile experience of reporting domestic violence to the police.

One of the founders of the now defunct Anti-Domestic Violence Network (ADVN), and co-founder of anti-domestic violence group Equality, Feng Yuan, tells us: “Kim Lee was important because it was reported by the media and also we [ADVN] supported her and helped her win her case. Her case set a very good example for many Chinese women: if you insist, you will find change.”

Now, the challenge lies ahead, with the law’s success largely dependent on its execution.

During a panel discussion about the new law, as part of the British Embassy’s Be Yourself campaign, director of Linxinwobang law firm, Yi Yi, said: “We have the law but now we need proper implementation. This means making the law feasible and practical, publication [of the law] through education, the media and the public, and comprehensive training for those in the judiciary system, juries and police, so that they can identify domestic violence and how to stop it.

“We need training and education at the grassroots level, because if they don’t know how to respond, they can’t act.”

During our Skype, Parkin is more specific: “I’d like to see more training of police in particular in how to respond to domestic violence and to assist women in getting the help that they need. This requires funding. The Chinese Government [should] commit more money to these efforts.”

The law’s provisions were quickly put to the test: On March 1 (the first day the law came into effect), two domestic violence victims filed for a personal protection order (PPO) at their local court in Beijing. That afternoon the court issued the city’s first PPO. A PPO lasts for up to six months and, depending on the situation, can be revoked or extended.

The recipient of the PPO, surnamed Gu, 61, had suffered abuse by her husband for 30 years, according to a news report by the Beijing Times & Legal Evening News. She stated: “I have endured his violence for so many years in [full] view of my two young children, but now they have grown up and I cannot bear it anymore.”

Yet, it remains uncertain whether the law will result in a flood of victims taking similar legal action against their abusers. Lack of education and access are just some of the huge barriers still facing women, in spite of the law.

One of the biggest hurdles, though, is changing society’s perception of domestic violence – behavior that has historically been deemed as ‘normal’ or, as previously mentioned, ‘private.’

While elements of gender discrimination can be found in Chinese society (one of Chinese philosopher Confucius’ Three Guidelines and Five Virtues in Confucianism states that ‘wives must submit to the husband’) it is a common misconception that patriarchy is a China-specific problem.

Still, individuals affected by domestic violence or authority figures often point to this idea – that domestic violence is an ingrained part of Chinese culture – when rationalizing abusive behavior. Parkin shares: “One thing I would often hear in domestic violence training in China was judges or police saying: ‘Well, this is China and [domestic violence] is a part of our traditional culture.’ It’s all very tied up in that conception of the traditional Chinese patriarchal system, but that’s just not true.

“Domestic violence is, at its heart, a crime of men against women. It’s an international phenomenon, occurring across cultures and countries with very different historical experiences. It’s a social phenomenon that human beings have to address.”

For example, Taiwan also has a traditional patriarchal culture. Yet, it was the first in Asia to implement laws aimed at preventing domestic violence with the Domestic Violence Prevention Act in 1998 and the Sexual Harassment Prevention Act in 2005.

After years of combating violence against women, Taiwan’s legislation resulted in a comparatively low rate of partner violence at 18 percent, according to research discussed at 67th World Health Assembly in Geneva in 2014.

So, it is possible to change perceptions. But, scenes encountered at the Maple Center suggest it is likely to be a bumpy road ahead.

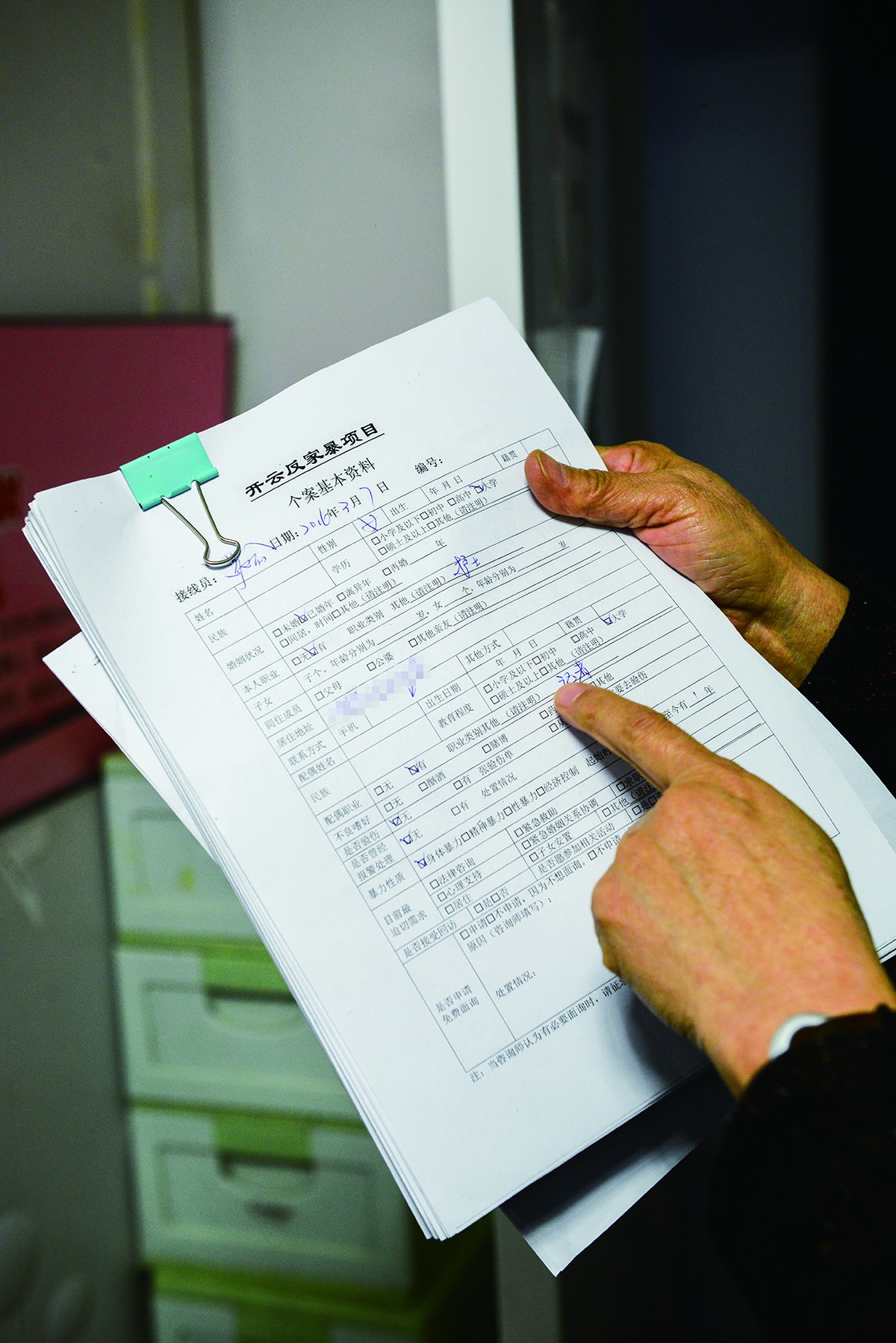

In the center’s counseling room, volunteer Hou Zhiming shares a logbook of case summaries, from calls made to the center’s hotline. It is a depressing read: perpetrators’ job descriptions include finance manager, designer, journalist, government official and, disconcertingly but perhaps unsurprisingly, police officer. Victims range from nurses to teachers.

The logbook is damning evidence that domestic violence is a problem that affects all strata of society. As Hou says: “It doesn't matter if people are [university] educated or not.”

A logbook of domestic violence cases received by the Maple Center.

In a recording of Hou’s most recent call, a 28-year-old woman named Wang* describes months of suffering abuse. Originally from Sichuan, Wang moved to Anhui to be with her husband. Wang called the hotline for advice after her husband hit her so hard he split her head open. She wants a divorce. Because of the domestic violence? Hou asks in the recording. No, because of his temper, Wang responds.

When Hou states this is an issue of domestic violence, the victim instead categorizes it as a ‘marriage’ problem. Apparently, she can endure the violent beatings; the deal-breaker is that her husband lacks similar ‘sanguan’ (fundamental values).

The conversation continues in this vein, with Wang admitting she is depressed even though the frequency of beatings has recently decreased. Furthermore, Wang says that upon seeing her husband for the first time after several days of absence, she still has feelings for him.

These are emotions experienced by victims of domestic violence across the world. But China’s legal framework can exacerbate them in unique ways. According to the Marriage Law, for instance, property owners are deemed to be whoever’s name is on the deed. Due to intense cultural pressure, many Chinese women live in their husband’s home, without their own legal security. Subsequently, they are at risk of losing substantial amounts of property in divorce cases.

The language of the law also promotes “family harmony,” much to Parkin’s disappointment.

“The approach that the government is taking is very much couched in this language of ‘peace’, which is unfortunate because the law should be about protecting women and vulnerable individuals from abuse,” she argues.

“There’s a heavy push for people to go through mediation rather than litigation, in order to keep the family together. But in an abusive relationship, there’s a power difference: If you have an abuser and an abusee in a room trying to mediate, you’re not going to get an outcome that’s going to protect the victim more.”

Despite Parkin’s skepticism of the “political buzzwords” in the law, she agrees with other experts that it is important to grant victims their own autonomy. “It’s about empowering women to be able to control their lives and get out of these relationships, rather than saying, we know what’s best.”

Perhaps most importantly, the law sends the unequivocal message that domestic violence is abnormal and simply unacceptable behavior in Chinese – or any – society.

While a concerted effort is required to bring about changes in attitudes toward domestic violence, the law is a step in the right direction. Because, as Hilary Clinton famously said at the 1995 Beijing World Conference on Women: “Women’s rights are human rights and human rights are women’s rights.”

* Names have been changed

The Domestic Violence Law can be read online here (Chinese) or here (English; search for ‘domestic violence law’).

For further information about the Maple Center visit their website or call the center’s anti-domestic violence hotline Mon-Fri 1-5pm (10 64073800; 10 64033383; 10 68333388). To report an instance of domestic violence in Beijing call 110 or visit your local police station.

Images by Holly Li

0 User Comments