By Aerled Doyle

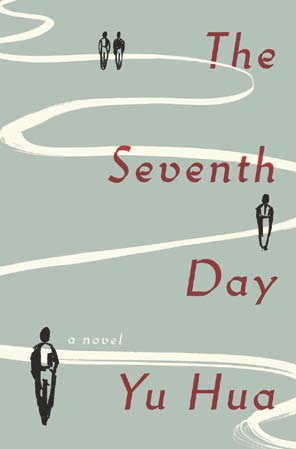

Yu Hua is a cunning writer. We didn’t take to his latest novel at first, particularly after being blown away by his two previous books, the witty, angry memoir China in Ten Words and the inspiring story collection Boy in the Twilight. But that’s on us; it took us a while to realize what he was doing.

When The Seventh Day begins, Yang Fei is already dead, with a 9.30am appointment for his own cremation. I a blurry, confusing city, he finds his way to the right place and takes his number to wait.

Some things never change: dead VIPs have their own area with comfy armchairs, while Yang and the other dead nobodies sit on plastic seats. But when his number is called, Yang realizes he has no grave, that there is nobody back in the mortal world to mourn him. He is not ready to go.

It’s an intriguing, sardonic opening. As Yang wanders the indistinct city of death, he begins to encounter people who once had some connection to him, and in the process remembers more clearly the events of his life.

His birth was freakish, a baby born in the bathroom of a moving train and lost on the rails beneath it, only to be rescued and brought up by gentle railway worker Yang Jinbiao. Jumping around the timeline, we learn about his death in a restaurant explosion, and we are told the story of his charming and successful ex-wife Li Qing, whose appearance in a newspaper distracts him on the day he dies.

There are more of these flashbacks, both of Yang Fei’s life and of other characters; the Capra movie would have to be called It’s a Horrible Life. Forced demolition of housing, dead babies treated like refuse, hushed-up disasters, Internet bullying – all rear their ugly heads.

Death seems quite pleasant in contrast, once Yang Fei escapes the gray, featureless city of death and finds himself in the “land of the unburied,” where “streams were flowing, where grass covered the ground, where trees were thick with leaves and loaded with fruit. The leaves were shaped like hearts, and when they shivered it was with the rhythm of hearts beating.”

Plus, everyone is nice to each other there! Yet all people ever do is worry about being unburied and wear black cloth on their arms to mourn for themselves. We felt like Yu’s characters were being ungrateful to the author. But as people tell their stories and Yang Fei finds his way to his father, people start to step out of their assigned roles. In fact, it’s in the very telling of their story that they can escape it.

Yu Hua has no time for cant, and even less for the clichés of the modern Chinese novel, and likes to intervene when his characters start behaving as convention dictates. So while many of the outcomes here are generic – saintly father figure sacrifices

own prospects for child, doomed young lovers are crushed by society but their love remains true, ambitious woman falls for rich man and throws over dull but reliable wage slave husband – the details are subversive.

Yang’s father could have married, but he was determined to be a martyr (and his final departure to die alone is foolish rather than noble). Li Qing is kind and cannot be blamed for the passivity of Yang Fei. Mouse Girl and Wu Chao make so many idiotic decisions that it’s hard to blame society – society keeps trying to feed and clothe them despite their best efforts.

Most admirable in this context are the mortal enemies who harried each other to death in life but now play endless board games while they bicker and refuse to move on to their cremations as they are supposed to. They’re enjoying each other’s company too much and no longer care about what they’re supposed to do.

This is a novel of the roles we choose to play and the roles we are allowed to play, and it’s clever and wise. Even our narrator’s death is unnecessary; while people flee a burning restaurant, he stays at his table, morosely reading about his ex-wife’s death. There’s a hell of a lot of injustice and evil out there, Yu suggests, but if we could all just get out of our own way that would help too. Living stupidly and dying stupidly are equally ignoble.

Yet Yu has always been a merciful writer, and while his satirical impulse works against his characters’ sense of themselves, we still feel for them, and sympathize with their fears and their failures to thrive. The metaphorical frame of The Seventh Day makes it less accessible than Yu’s earlier books, and it’s not the one new readers should start with. But it lingers, and it comforts while it chills. He is a master writer.

// The Seventh Day (Random House) is available on Amazon.

0 User Comments