Throwback Thursday is when we trawl through the That's archives for a work of dazzling genius written at some point in our past. We then republish it. On a Thursday.

Modern Chinese literature is often overshadowed by a single name: Lu Xun. Indisputably one of the most influential of the 20th Century authors, he is for many Western readers the sole representative of the post- dynastic period, casting peers and heirs into darkness.

Despite his towering reputation, Lu Xun was not the only writer to institute literary reforms and encourage the use of vernacular language. Equally important as a catalyst for change – though far less recognized outside his native land – was Lao She.

Born Shu Qingchun in 1899, he grew up in poverty in Beijing alongside two siblings, and supported solely by his mother. His father, a soldier, had been killed in 1900 while defending the capital from foreign forces during the disastrous Boxer Rebellion.

The conflict, begun by the Society of Righteous and Harmonious Fists and backed by the Qing Dynasty, sought to relieve the humiliations forced upon the Chinese in the aftermath of the Opium Wars; it ended in further ignominy and mass looting by a coalition of German, Russian, British, American, French, Italian, Austro-Hungarian and Japanese troops.

It was a defeat that colored Lao She’s whole life, engendering complicated mixed feelings about the Western powers. Though he, like all intellectuals connected with the New Culture Movement, derived many of his inspirations from them, he was also greatly affected by the violence of these ‘civilized’ nations, who displayed undisguised contempt for the Chinese.

In an oft-quoted remark, he even went so far as to say, “During my childhood, I didn’t need to hear stories about evil ogres eating children and so forth; the foreign devils my mother told me about were more barbaric and cruel than any fairy tale ogre with a huge mouth and great fangs.”

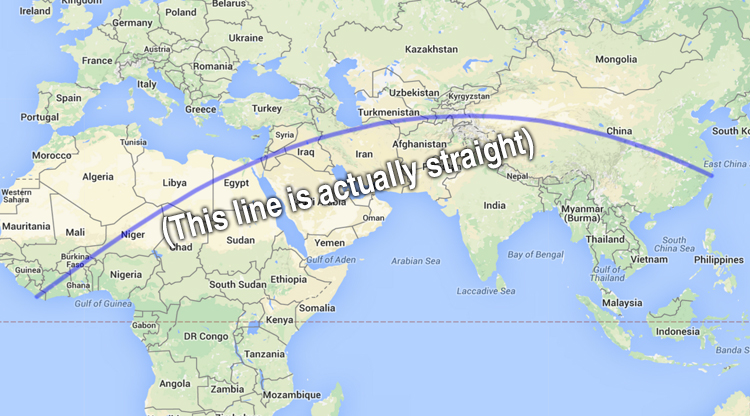

Unlike Lu Xun, who never ventured further afield than Japan, Lao She actually lived several years in Europe. Converting to Christianity in 1922, two years later he managed to obtain a position at the School of Oriental and African Studies (then just the School of Oriental Studies) with the aid of the Reverend Robert Kenneth Evans. During his time in England, he wrote his first three novels, shaded by readings of authors like Dickens.

While in London, he witnessed how ‘Yellow Peril’ propaganda – then pervading most countries around the world with a predominantly white population – had whipped up popular fear of the ‘Chinaman,’ an inferior yet sly and dangerous breed of person, forever puffing away on his opium pipe and plotting.

"I didn't need to hear stories about evil ogres eating children and so forth; the foreign devils my mother told me about were more barbaric and cruel than any fairy tail ogre."

Some historians have suggested that anti-Chinese sentiment was so high during the early 20th Century that the race was despised and feared above all others. Lao She played upon this prejudice in the London-set Mr. Ma and Son, where the Chinese are singled out as savages and compared unfavorably to their fellow Asians, the Japanese.

Lao She decided to leave Britain in 1929, heading home via a brief stint teaching in Singapore. He took up a series of positions at different universities, simultaneously writing and publishing several works, notably his magnum opus, Rickshaw Boy.

With the advent of WW2, Lao She was galvanized into political action. Heading up the All-China Anti-Japanese Writers Federation (Zhonghua Quanguo Wenyijie Kangdi Xiehui), of which other esteemed literary figures like Guo Moruo and Cao Yu were also members, he wrote patriotic pieces in a variety of mediums, designed to buoy the public up against the invaders.

Following the end of the war, he traveled to the United States for three years on a cultural grant from the Department of State, but returned in the wake of China’s Communist Revolution in 1949.

At first, he backed the new social order, perhaps hoping that finally, after many years of seeing his beloved homeland as backward and weak, China would rise in power and respect.

Bestowed with the title of ‘People’s Writer,’ Lao She was showered with numerous positions: deputy to the National People’s Congress, member of the Standing Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, vice-chairman of the Union of Chinese Writers and vice-chairman of the All-China Federation of Literature and Art, among others.

All this prestige quickly disintegrated with the dawn of the Cultural Revolution. As an intellectual figure who was ethnically Manchu (like the Qing Dynasty) and had known connections to the West, the now-elderly writer was one of the earliest people targeted by the Red Guards. Labeled a counterrevolutionary, on August 23, 1966, he was vehemently denounced and viciously beaten, by some accounts until he passed out from the pain. By this time, Lao She was aged 67.

With the threat of further violence hanging over his head, the next day he headed to the Lake of Great Peace (Taiping Hu) and drowned himself. Twelve years later, the Communist Government ‘rehabilitated’ his image, and today he is taught in schools across the country.

Lao She left behind a wealth of work that documented the Chinese experience – both at home and abroad – through the lens of bitter satire. His writing, noted for incorporating colloquial Beijing dialect, is often said to be far more hopeless and pessimistic than Lu Xun’s – but then again, Lu Xun died in 1936, and never witnessed the atrocities of the Sino-Japanese conflict, the horrors of the Civil War or the tragic stumblings of the early People’s Republic of China.

Perhaps if he had, he would have said Lao She’s visions of the average man, his spirit crushed underfoot again and again by a steady stream of people blindly marching on, were justified.

This article first appeared in the September 2013 issue of That's Shanghai. To see more Throwback Thursday posts, click here.

0 User Comments