This feature is part one of our June 2018 cover story. Check out the full issue in digital pdf form right here or in your browser here.

"Excuse me,” a woman asks a group of security guards outside Beijing Zoo in Xicheng district. “Can you tell me where the wholesale market is?”

“There is none. It’s gone,” the guards reply in unison.

“What about Dahongmen Market?” the woman asks, though, that, too, has gone.

“This happens every day,” a guard tells me later.

Built in the mid-1980s, the ‘Beijing Zoo’ wholesale market, named for its location, was every shopper’s dream. Comprised of 12 buildings and housing 130,000 stalls over 350,000sqm, the wholesale market was once the largest clothing distribution center in Northern China, with customers numbering 100,000 per day, according to China Daily.

Made up of thousands of stalls, the complex sold truckloads of clothes straight from the manufacturer at stunningly low prices – ‘3 items for 100 kuai’ read the handwritten signs. The Beijing Zoo wholesale market was where people of all ages and nationalities came together, united in the name of consumerism and cheap knockoffs.

But in 2013, authorities announced plans to relocate the market to the surrounding Hebei province and Tianjin. The move, also known as the ‘Dongpi’ project (‘pi’ deriving from ‘pifa shichang,’ meaning wholesale market, and ‘dong’ meaning to move), is part of the local government’s attempt to clear Beijing of “big city ills” like pollution and traffic, as well as cap the population at 23 million by 2020. By getting rid of non-essential businesses – like the markets – the city could focus more on high-tech business and professional services. Although the market contributed RMB60 million in annual revenue to Xicheng district, it also cost the government around RMB100 million in transportation and pollution fees, according to government reports.

In 2015, the capital started shutting down the zoo markets and the final building closed last November. The long, drawn-out closure was painful for both locals and tourists alike. No more haggling over the price of a pair of jeans that would go out of fashion in half a year, no more stocking up on fake Gucci bags to gift relatives back home – no more cheap adulterated thrills.

The Baolan Financial Innovation Center takes the place of the former Beijing Zoo wholesale market

The market has since been demolished and replaced by a modern but gray – and especially so on the rainy day I visit – building called the Baolan Financial Innovation Center, which is mainly occupied by tech firms. The once-bustling area is noticeably cleaner and more subdued.

“It’s better here than before,” one of the security workers, surnamed Zhang, tells me. “Before there were too many people, and too much rubbish and traffic.”

But Beijing Zoo is just one market that’s been affected. The government-led action resulted in the termination of 302 wholesale markets in total in 2015 and 2016, and 120 establishments were targeted last year. This year alone has seen the fall of multiple electronics markets and flower markets, while whispers of the imminent end plague others.

“It’s better here than before. Before there was too many people, and too much rubbish and traffic.”

The gravitas was felt at Tianyi Market, what was Beijing’s largest small commodities wholesale market, when it closed last September. Shoppers and vendors recorded the monumental closing day on their phones as ‘Auld Lang Syne’ played over the speakers, reported China.org.cn.

And while many markets are not strictly closing, they are moving so far away that they may as well be dead to the average shopper in the capital.

“Beijing has initiated a lot of policies to decentralize the population and [improve] the functioning of the capital. Relocation of the wholesale markets is one such policy,” explains Tang Yan, an associate professor at the School of Architecture of Tsinghua University.

I ask Tang, who specializes in urban design and strategic planning, whether she thinks it’s a good idea.

“Not really,” she says bluntly. “It’s a two-sided coin. In the future, for a city like Beijing, the land should be used efficiently, especially for high-end services, not low-end wholesale markets.

“But right now, the problem is that this policy has pushed the markets out of the center city immediately, and in such a short time that it’s bound to cause some problems. There are people with businesses whose lives have been totally changed because of this movement. We can’t judge if their business [in the new location] will be as successful as in central Beijing.

“It’s better to do it step by step,” Tang suggests. “The three most important wholesale markets located in central Beijing were Beijing Zoo, Dahongmen and Tianyi. They were the main targets for the government – but maybe it would have been best to move one first, reconstruct it and see the result – and then do the next one.”

“This policy has pushed the markets out of the city in such a short time that it’s bound to cause some problems.”

Now, shoppers are forced to journey to undeveloped towns in our neighboring areas to chase a steal. To places like Baigou, a small town in Hebei province, where some Beijing markets have been moved to.

A future vision for Baigou is displayed at the Baigou Museum and Urban Planning Exhibition Hall

The high-speed rail journey from Beijing to Baigou takes just over an hour. In winter the landscape is arid farmland, but during spring the bright green fields make for a pleasantly scenic train ride. After alighting at the town’s 2-year-old station, it is a 20-minute drive on the lawless highway and through narrow backstreets, before emerging in the town center, where trees and an assortment of buildings, new and old, line the wide streets. There are scant cafes here, and no McDonalds.

Baigou is known for being a luggage-manufacturing hub (a larger-than-life sculpture of suitcases sits at the entrance to the Baigou Museum), but these days, the garment industry is taking over, with 300,000sqm of land marked to house the new locations of the Beijing Zoo and Dahongmen markets.

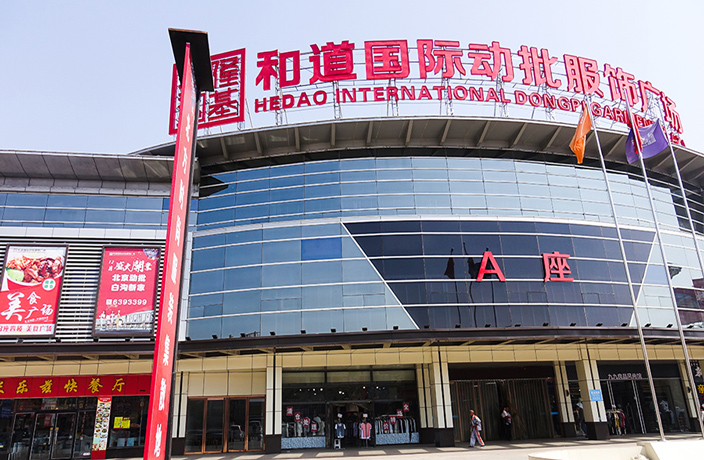

Many of the vendors moved to Baigou’s Hedao International Dongpi Garment Plaza. The recently built market stands out from its surroundings, thanks in part to the sky-high apartment complexes directly behind it.

Baigou’s Hedao International

Dongpi Garment Plaza houses vendors

originally from Beijing

“There used to be a market here selling bags,” a security guard outside the plaza tells me. “This [new] market is good for the economy and convenient for both local people and the shopkeepers that came from Beijing. When the time comes, there will be more people shopping here.”

Looking around, there are only a handful of people in the area. But there are plenty of smartlooking shops inside, each selling a smorgasbord of ironic T-shirts, counterfeit Nikes and fake Supreme gear. Some shops lie empty, though with signs plastered on their windows, the names of Beijing markets scrawled on them.

On the ground floor I meet storekeeper Su Zhiguo, whose shop sells Adidas trackpants. He moved to Baigou last December after seven years at Beijing Zoo. “I’d like to stay,” he says. “Delivery is speedy, because the area used to sell bags, so the logistics facilities here are already well established.

“Business isn’t that great right now, not as good as it was in Beijing,” the Tianjin native admits. “But I’ll wait and see how the area develops. I’m looking forward to it.”

Cheap T-shirts for sale at the Hedao Garment Plaza

Beijing Zoo transplant Su Zhiguo sells tracksuits at his relocated shop in Baigou

Su refers to the Xiong’an New Area development that was announced in April last year and touted as the “new Shenzhen.” An amalgamation of three neighboring Hebei counties, the New Area will serve as a development hub for the Jing-Jin-Ji (Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei) economic region, and an RMB2.4 trillion of investment will engulf the area over the next decade, according to a report by Morgan Stanley. Located a few minutes’ drive from the New Area, those in Baigou are hoping to see some of the windfalls.

As part of the local government’s ‘preferential policy,’ Su, along with the other Beijing Zoo vendors who moved to Baigou, is exempt from paying three years of rent. The government also provides housing assistance and medical care, as well as school enrollment for storekeeper’s children.

Wang Lei, another Beijing Zoo transplant, tells me that while there is a “plan” regarding schooling, it hasn’t been implemented yet. “I have children but I’m not that keen to let them study here in Hebei, because it’s such a big change for them – they have to adapt to a new environment and it’s challenging,” he says as pop music blares in the background of his store.

“Plus, the education they would receive in Beijing would definitely be better,” the Anhui native continues. “But it’s all part of the policy and we have to follow it. And because it’s a city policy, many people have come here together from Beijing, making us feel less alone.”

Vendor Wen contemplates business at his new Baigou store

Walking through the plaza, the higher the floor, the emptier it is. One shoe store is completely bare but for a single pair of lonely sneakers perched on a stand. Generic lobby music, the kind that anyone who has spent more than a few days in Beijing will recognize, plays in the background while trios of colorful, yet uncomfortable-looking, stone-shaped seats litter the floor.

It takes some effort to track down a customer to talk to – there aren’t many. But I find Shijiazhuang local Xing Yujiao, who drove here with her family after hearing about the Dongpi project. “We were considering buying some clothes here to bring back and sell in Shijiazhuang,” she says. “But the market isn’t very mature now, and the types of clothes are too simple. We’re a bit disappointed.

“We’ll find another place to source our clothes from. Perhaps in the south of China, if there are no suitable places in Beijing.”

Meanwhile, Zhang Lijuan, a Laobeijing, is enjoying a daytrip to Baigou with a friend. “We followed a travel agency car,” she tells us excitedly (even though they are not part of the agency's tour group). “It’s my first time here and I think it’s OK. Goods here are cheaper than in Beijing. I’ll be back.”

Zhang may not have a choice, as back in Beijing, markets continue to close at regular pace. A notice outside a stall at Beijing’s Liangma Flower Market reads: The last few days, hurry man! Until the end of April. BIG SALE.

Flowers for sale at the Liangma Flower Market

A sign at Liangma Flower Market reads "Hurry man!!!"

The market is a treasure trove of cheap kitchenware, kitschy decorations and, naturally, flowers. But when I visit, 72 hours before final closing time, everything is on sale, and many vendors have already left the building. I ask a woman selling lilies on the ground floor what her plans are after the market closes and she hands me a colorful flyer: It’s an advertisement for a new flower market that’s being built, just down the road, near Solana Shopping Mall.

But unlike the Baigou market and its preferential policy, the new flower market isn’t a government-backed initiative, and without any incentive, vendors from the Liangma Market are less inclined to move.

“What if we move over there and then they demolish that market, too?”

“Everyone here has to find their own new place,” a woman, surnamed Li, tells me. “It’s very bothersome – the new market is too expensive. For example, this here,” she points to a bowl, “is RMB200, but in the new place I’d have to sell it for RMB400 [because of the increased rent].”

Her husband adds: “Even if we moved there, there wouldn’t be many customers [because of the increased price of goods]. They are going to demolish this market and turn it into a park.”

Another vendor I talk to, Su Yanli, isn’t moving to the new market, either.

“What if we move over there and then they demolish it?” the Hebei native asks. “They only gave us one month’s notice. We still have so many goods left,” she laments. “So first, we’re just going to store our goods somewhere and then think about our next move.”

Stuffed-animal seller Liu, originally from Henan, hasn’t found a replacement shop yet, either. He thinks that the proposed park development will be good overall for Beijing’s environment, and yet “with all the markets getting demolished, it’s difficult to make money, and if you don’t have a house here, then you’re a beipiao [drifter]. It’s getting harder and harder to be a migrant in Beijing these days.”

Storekeeper Liu prepares to close for good

The Beijing market closures also have a negative effect on those who rely on purchasing from the markets to do business themselves.

Just ask Glenn Schuitman. Originally from New Zealand, Schuitman has been living in Beijing for over 12 years. The interior designer and antique dealer relies on a wide range of local providers to source his products, including many markets, factories and warehouses that were previously located within Beijing municipality, he says.

“Before, with some good planning, I could move between a supplier's factory and a couple of warehouses in one day – as long as they were in the same sub-district,” Schuitman says. “Now, it’s a full-day trip to simply access one venue. It makes it much more challenging.”

Yet China has the biggest e-commerce market in the world. Last year saw 553 million people buy goods online and, by 2022, revenue from business-to-consumer sales is expected to surpass RMB6 trillion, according to Statista. Buying online in China is the norm, thanks to a multitude of reasons, including the ease of making digital payments and, as in the wholesale markets’ case, forced physical closures.

Schuitman concedes that many vendors have moved to online selling, though he prefers seeing the fabric in the flesh. “While it’s not impossible to do that using Taobao, it takes so much time to get a vendor to send a sample, trial it, then place an order, and wait for the final delivery,” he explains.

“Project-planning timeframes are significantly changed as a result, but clients don’t understand why – and that’s only for fabric! And even though I have long-standing relationships with market vendors – such as the vendors at the wholesale flower market – I feel as if I’m continuously chasing them around the city, to their latest temporary location. It’s not great for me – but it’s far worse for them.”

After the markets have cleared and the people have moved – to Hebei, to Tianjin, or, back to their hometowns – there’s still the question of how to make use of the space.

“It remains unclear,” Professor Tang admits. “Not only for the government, but also for the planners. In the short-term, we don’t know. Maybe it will be empty for several years.”

But what about the plans vendors have told me about – like the park in Liangmaqiao?

“It’s easy to make a plan,” Tang says. “But it takes time to turn it into reality – and there’s always a cost.”

Perhaps the past is the best indicator for the future. When I first arrived in Beijing in 2013, a friend took me shopping at Yashow, a ramshackle wholesale market beside Sanlitun’s flashier Taikoo Li South shopping mall. After bargaining with the sellers I bought some socks and my friend bought a pair of sunglasses with blue-colored lenses.

In December 2014, the market closed for renovations and nine months later, a slicker, cleaner version opened. It was Yashow, but in name only. Gone were the stalls selling dirt-cheap designer knockoffs, and in their place were shops filled with boutique-wear at boutique prices. Gone, too, were the people.

Most of Yashow’s vendors shut and left. The market closed again last year, and months later, exactly three years after its first closure, it was announced that it would be renovated – a second time – by property developers Swire Properties and building owners Beijing Kuntai Real Estate Development Group. They would turn the space into something even glitzier: ‘Sanlitun Taikoo Li West.’

Beijing, Beautified: A Timeline of Changes in the Capital

October 23, 2016

Baochao Hutong becomes one of the first alleys to be suddenly renovated

April 24, 2017

Sanlitun’s ‘Dirty Bar Street' gets bricked, forcing many businesses to close

May 23, 2017

Fangjia Hutong’s popular bars are bricked up

September 16, 2017

The famous Tianyi Wholesale Market is forced to close

September 27, 2017

China announces it will limit Beijing's population to 23 million by 2020

November 1, 2017

Beijing implements tighter restrictions on rooftop signs

November 10, 2017

Beijing bans vehicles from parking in hutong alleyways less than 5 meters wide, says hutongs from five to nine meters wide can only allow one-way traffic

November 18, 2017

A deadly fire breaks out in Daxing district, which spurs government-led ‘safety inspections’ that result in the sudden demolition of hundreds of homes and businesses on the city’s fringes

November 30, 2017

The final market of the Beijing Zoo wholesale market complex shuts its doors

December 1, 2017

Beijing bans all fireworks within the Fifth Ring Road

April 30, 2018

Authorities close the Liangma Flower Market

This feature is part one of our June 2018 cover story:

READ MORE: That's Beijing – June 2018 Issue Out Now!

0 User Comments